54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Colored)

by Dr. George H. Junne, Jr.

The most famous African American regiment of the Civil War was the Massachusetts 54th, renowned for its assault on Fort Wagner. Located near Charleston on Morris Island, Wagner was one of several fortifications built to protect the city and its harbor. There were many people, both high and low, who banded together to fight for the creation of the regiment. Among them was John Albion Andrew, the wartime governor of Massachusetts; Frederick Douglass, the former slave who fled to Massachusetts and became a newspaper man and politician; and Robert Gould Shaw, the young Boston blue-blood officer who reluctantly agreed to lead the command. It would be Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863 that would “kick open the door” for the possibility of African Americans to fight for their country. Recruitment for the 54th was so successful that within a few months, a sister unit, the 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment was created and later, the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment. On July 18, 1863 the 54th Massachusetts attacked Fort Wagner. At about 6:00 p.m., Colonel Shaw led the charge on his horse and carrying the national flag with his men marching closely behind. With all of the Confederate weapons focused on that narrow area, the casualties were high. It seems impossible, but Colonel Shaw and some of his men managed to climb up the front of the fort and take the fight inside. Shaw was wounded and soon killed leading the fight inside the fort. All of the officers leading the 54th had become casualties but the men refused to surrender and were slaughtered. Shaw had led 600 enlisted men and twenty-two officers in the battle at Fort Wagner and the unit suffered 272 casualties. Nearly 300 had actually managed to get inside the fort and fight. In the aftermath, the Confederates buried Colonel Shaw with his Black soldiers as a sign of disrespect. Northern newspapers carried stories about the bravery of the 54th under fire and because of their courage, many were forced to reevaluate their racist views of African American soldiers. Boston remembered the 54th on May 31, 1897, with the unveiling and dedication of the Shaw Memorial.

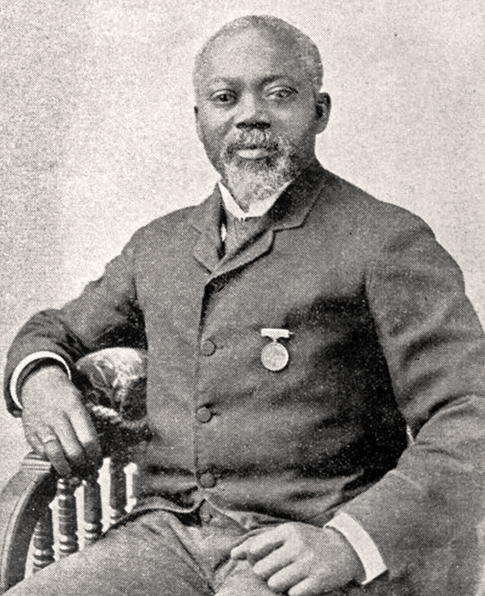

William Harvey Carney Medal of Honor, 54th Massachusetts

Image credit: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library

Oh! not in vain those heros (sic) fell,

Amid those hours of fearful strife;

Each dying heart poured out a balm

To heal the wounded nation’s life.

And from the soil drenched with their blood,

The fairest flowers of peace shall bloom;

And history cull rich laurels there,

To deck each martyr hero’s tomb.[1]

The most famous African American regiment of the Civil War was the Massachusetts 54th, renowned for its assault on Fort Wagner. Located near Charleston on Morris Island, Wagner was one of several fortifications built to protect the city and its harbor. That famous battle was only one of the important engagements in which the regiment fought; the most difficult might have been the struggle for the acceptance of African Americans as soldiers, the battle for equal pay and the continual fight for dignity and respect.

There are many people, both high and low, who banded together to fight for the creation of the regiment. Among them was John Albion Andrew, the wartime governor of Massachusetts; Frederick Douglass, the former slave who fled to Massachusetts and became a newspaper man and politician; Robert Gould Shaw, the young Boston blue-blood officer who reluctantly agreed to lead the command; Lewis Hayden, escaped slave, messenger to the Massachusetts secretary of state and friend of Andrew; abolitionist and 54th recruiter George Luther Sterns; the African American community of Boston; and many others, including a group of African American women of Boston who volunteered to fight if needed.

African Americans had fought in previous American wars, beginning with the French and Indian War (1756-1763), the Revolutionary War, and the War of 1812. Unfortunately, however, within a few years following those events, their participation was forgotten. It was only after the release of the 1989 Hollywood film Glory that most Americans became aware of the role of just one of the African American regiments.

From the firing on Fort Sumter, April 12-13, 1861, the event that triggered the Civil War, African Americans attempted to volunteer to fight for the Union, but were rebuffed. Many believed the war would only last ninety days and it was not to be a Black man’s war. Further, many Northerners, including President Lincoln, did not want the conflict to focus on ending slavery, which certainly would happen if African Americans were involved. Early on, Governor Andrew, Frederick Douglass and many others knew that the military operations would continue beyond ninety days and began to agitate for Black enlistment.

It would be Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863 that would “kick open the door” for the possibility of African Americans to fight for their country. The Proclamation stated, regarding slaves: “And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”[2] Pressure from the governors of Massachusetts and Rhode Island, plus many others, used that phrase intended only for guarding military sites to recruit African American regiments. Massachusetts would be credited with the first African American Civil War fighting unit recruited in the North.

Governor Andrew had to obtain permission to raise two regiments for Massachusetts. He would also appoint their officers and would have to recruit and train the men. He had traveled to Washington and made a direct request to Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War, in January 1863. A few days later, Andrew received the authority to recruit for the Massachusetts 54th, designated the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Colored). In the following days, Andrew began to agitate for the promotion of African Americans to the position of officers, which at that time was not acceptable to the Lincoln Administration. Immediately, though, in coordination with Lewis Hayden, Frederick Douglass, George Luther Sterns and many others, he began to assemble recruiters for his new venture.[3]

Initially, there was some concern that African American men would not enlist in a war in which they knew they were not wanted. As residents of Massachusetts, particularly Boston, many younger men had very good jobs and a supportive community not found in other Northern states. What many people did not understand was that African Americans were patriotic, no matter how negatively they were treated, even in the North, and did not want to see their state invaded and slavery expanded. They also knew that in spite of the rhetoric, slavery would still be an issue. After the war would end, they did not want White people to say that they freed Black people, but that Black people freed themselves. Recruitment for the 54th was so successful that within a few months, a sister unit, the 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment was created and later, the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment.

The men trained at Camp Meigs, located in Readville, Massachusetts, a few miles from Boston and near a railroad station. Because of White opposition against African American soldiers, White friends purchased train tickets for them and the men were advised to only travel at night. Still, men came to receive a detailed physical and if they passed, to enlist. By the war’s end, approximately 1,280 had enlisted in the 54th, mostly from Massachusetts but also about 50 from Michigan, 155 from Ohio, three from the West Indies and twenty-five from Canada. They all arrived at Camp Meigs where their White officers transformed them into soldiers.[4]

A major concern centered on who would be the officers of the new unit and Governor Andrew attempted to guarantee that they would treat the men fairly. He relied heavily on soldiers from the abolitionist community, such as the Hallowell brothers, as well as others who wanted to volunteer. Prospective officers were interviewed and if they used racial epithets, they were excluded. To lead the 54th, Robert Gould Shaw’s name was proposed. He was a Harvard student from a prominent abolitionist family, a merchant, and a seasoned veteran of the Battle of Antietam. When Governor Andrew contacted Shaw to lead the 54th, he turned down the offer at first, which distressed his mother. After reconsideration, Shaw accepted the offer.

It was near the end of February 1863 when the first men arrived at Camp Meigs and by the end of May, the overflow formed the Massachusetts 55th. Approximately one hundred a week went to volunteer their services. About a third of the prospective enlistees were rejected for medical reasons. Some fell ill and a few died. Men bathed in a pond, which led to further illness and even death for some. Men and officers arose at 5:30 a.m., cleaned their barracks and dressed, all by 7:00 a.m., whereupon they drilled for five hours after breakfast and again after lunch and dinner. Lights-out was 8:30 p.m. There was limited time for recreation. Some soldiers took reading lessons from volunteers. Newspaper reporters arrived to write about this new phenomenon. Some papers were racist while others tried to accurately report how the men were becoming soldiers.[5] The national government did not allow African American clergy but since Meigs was a state camp, Governor Andrews was able to appoint two for leading religious services. In late July, Samuel Harrison, a Congregationalist, received authorization to become the unit’s official African American chaplain.[6]

Two sons of Frederick Douglass, Lewis and Charles, were early enrollees in the 54th. Letters from them and others talked about the discipline and difficulties of military life and there were some desertions but overall, the officers began to gain respect for the men. Colonel Shaw fought for his soldiers and in one instance, sent back uniforms intended for them because of the dark blue color. Shaw realized those were the colors of contrabands, former slaves serving in Southern units, and had his men shipped the standard uniforms the regular soldiers wore. Shaw also made sure his men were armed with the best rifles at the time, the British-manufactured Enfield rifled muskets. Shaw still held some racist ideas about his men but he was gradually evolving, as were his men as they were turning into first-rate soldiers.

Townspeople from Boston began to travel to Camp Meigs and stared in amazement as the 54th drilled. The men knew that their success or failure would influence other attempts to form Black units. They excelled at parade and kept the grounds very clean. Their weapons were always clean and polished and most participated in the morning and evening prayer services. Punishments were strict but fair and Shaw made sure the punishments would not reflect that of slaves. At one point he wrote that his men were treated better than the Whites in his former regiment. Further, his men excelled in some areas even better than the Irish he previously commanded.

Shaw was able to recruit two Hallowell brothers as officers, Edward Needles Hallowell as colonel and Norwood Penrose Hallowell as lieutenant colonel. Like Shaw, both were from prestigious families and both worked with the Underground Railroad, assisting escaped slaves. Choices such as this helped to guarantee that the men of the 54th would be treated relatively fairly. In May, the unit was officially mustered in, signaling it was ready for battle. A couple days later, word arrived that the 54th would be sent to South Carolina under the command of Major General David Hunter at Hilton Head.

The regiment’s colors were presented at a ceremony attended by a few thousand people that included Governor Andrew and famous abolitionists. Shaw gave a short speech. During the ceremonies, a messenger rode up with a telegram stating the 54th was to proceed immediately for Hilton Head. There was another ceremony held in Boston at the end of May and approximately 20,000 people turned out. There were some minor incidents such as boos and hisses from pro-Confederate rabble, but Governor Andrew reviewed the men on the Boston Commons and Frederick Douglass, among others, gave speeches. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier and Louisa May Alcott were in attendance, as some attendees gave bags of cookies and cigars to the soldiers. The crowd followed them to the wharf where they embarked for Hilton Head.[7]

Their ship, the DeMolay, was brand new as it embarked from Boston’s Battery Wharf on its uneventful journey to Hilton Head, where it arrived on June 3. Shaw reported to General David Hunter, who ordered the unit to sail to Beaufort, South Carolina, to be attached to the X Army Corps on Saint Helena Island.[8] Upon arrival, newly freed slaves, who had never seen Black men in uniform, enthusiastically greeted the 54th. Both Blacks and Whites had lined the street to catch a glimpse of them marching through the town on their way to their campgrounds.

Colonel Shaw noted immediately that the 54th and other African American regiments from the South, the 1st and 2nd South Carolina, were located in a swampy area infested with mosquitoes, terrible food and a lack of equipment, while the White regiments camped in a pleasant site with good food and the best of equipment. After being told that the White commander of the area did not like the idea of having Black troops, Shaw telegraphed Governor Andrew, who telegraphed the War Department, and changes were immediately made.

The 54th was then ordered to report to Colonel James Montgomery of the 2nd South Carolina, who would lead them and his men on a shameful mission. Leaving with all except two companies of the 54th and taking five companies of the 2nd South Carolina and some companies of the 3rd Rhode Island Artillery, the men left for Darien, Georgia, which was deserted. Montgomery ordered the 54th to loot the homes, farms and businesses for anything that could be used in camp, and then torched the town, including a church. This was part of Montgomery’s “scorched-earth policy.” Perhaps, he believed he was wreaking revenge on the town where the first meeting was held that drafted the state’s Ordinance of Secession.[9] Shaw complained to superiors about his men being used for such purposes against civilians. After the war, Shaw’s mother sent two $500 checks to the church’s rector to be used to build two churches in honor of her son.

Later in June, Brigadier General Quincy Adams Gillmore, a former instructor at West Point, replaced Colonel Montgomery. On June 30, a day before the Battle of Gettysburg, the 54th mustered for pay and learned that instead of being paid $13 a month as previously, they were only to be paid $10 a month. Shaw immediately began to complain and in a show of solidarity, men and officers of the 54th refused their pay until the enlisted men would be paid $13 a month again. For many of the men and their families who depended on that money, the shortfall was painful.

Meanwhile, the 54th excelled at marching and at parade, something even some of the White soldiers grudgingly admitted. Shaw knew that unless he could demonstrate that his men were prepared for battle and could give a good accounting of themselves, there would always be doubts about their abilities. Shaw contacted Brigadier General George Crockett Strong and requested that the 54th be transferred to the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, X Corps in the Department of the South. Shaw wanted his men to fight beside White soldiers so they could see how qualified they were.

The 54th was to join General Quincy Gillmore’s army in its attempt to take Charleston, South Carolina. However, Charleston was protected by a series of forts that had to be taken first because they prevented the Union Navy from approaching the city. Rear Admiral John Adolphus Bernard Dahlgren was to lead the naval attack on the forts in coordination with Gillmore. Three of the targeted islands were James, Sullivan and Morris, the latter on which both Fort Wagner and Fort Gregg stood, with Gregg protecting Wagner.[10] Defeating the forts on James and Morris Islands was seen as the key to capturing Charleston.

On July 16, 1863, the 54th received its first taste of battle on James Island, where three companies were on picket duty. Confederates attacked and overran the men in hand-to-hand combat. Some of the 54th fought to the death, a few surrendered, and others were forced back into a swamp. Still, they repulsed the enemy and held their line, allowing the 10th Connecticut Infantry to retreat and for reinforcements to arrive. Men from the 10th praised the 54th for their bravery because it prevented their capture by General Beauregard.[11] The three companies of the 54th had fourteen men killed, eighteen wounded and thirteen missing or captured.

Two days later, the Massachusetts 54th would engage in its most famous battle, the attack on Battery Wagner, known as Fort Wagner. Shaw had been pushing for his soldiers to lead the charge and informed General Strong that he wanted his men to lead in a real battle, not a skirmish. General Gillmore, Strong’s superior, accepted the offer, not because he believed in the 54th, but because he believed they would fail, and he could get rid of them. Therefore, those who wanted the 54th to succeed and those who did not want African American soldiers had their own reasons for having the regiment lead the charge.

The Union Army, through faulty intelligence, believed their army outnumbered the Rebel forces by a ratio of 2:1. In fact, the odds were reversed with the Rebels holding a 2:1 advantage. In addition, the Federals did not know that Fort Wagner was one of the strongest forts ever constructed in the United States. Most of the guns were aimed toward the route that the attackers would have to take in storming the fort.

The Union Navy bombarded the fort to little effect. When the firing ceased, those inside would make needed repairs and retreat inside into safe shelters called bombproofs. Further, on the ground approaching the fort, the island narrowed so that men on either flank of the regiment would have to wade in seawater up to their waists.

About 4:00 p.m. on July 18, the 54th, which had gone two days without rations because of the march toward Wagner, were preparing for the attack scheduled to begin that evening. Shaw, having a strong premonition that he would not survive the battle, gave all of his papers and letters to a friend for safekeeping.[12] General Gillmore organized three brigades. The 1st Brigade was composed of units from the 6th Connecticut, the 7th Connecticut, the 48th New York, the 3rd New Hampshire, the 9th Maine, the 76th Pennsylvania and the 54th Massachusetts. . At about 6:00 p.m., Colonel Shaw led the charge on his horse and carrying the national flag with his men marching closely behind, approached Wagner where the land narrowed to about 100 feet. Six hundred men of the 54th were the troops in the front of the charge. Their muskets were primed and bayonets ready, but they were ordered not to have their firing caps in place. They advanced so quickly that at one point they were ordered to lie down and wait for the other units to catch up. Some of the soldiers were walking in the ocean. With all of the Confederate weapons focused on that narrow area, the casualties were high. As they approached the slanted front of Wagner, the Rebels rolled grenades, called “torpedoes,” down onto the attackers. In spite of all of this, the 54th had been ordered not to fire a shot until inside the fort, and they obeyed their orders.

It seems impossible, but Colonel Shaw and some of his men managed to climb up the front of the fort and take the fight inside. Shaw was wounded and soon killed leading the fight inside the fort. To further complicate matters, shelling from Union boats began during the charge and Union troops to the rear of the charge also began firing on people on the fort’s parapet, believing they were only firing at Confederates. In the melee, Sergeant William H. Carney became separated from the others. Holding the flag, he went towards a group and at the last moment, recognized that they were the enemy. He was shot multiple times but refused to drop the flag.[13] At this time, all of the officers leading the 54th had become casualties but the men refused to surrender and were slaughtered. Shaw had led 600 enlisted men and twenty-two officers in the battle at Fort Wagner and the unit suffered 272 casualties. Nearly 300 had actually managed to get inside the fort and fight.

In the aftermath, the Confederates buried Colonel Shaw with his Black soldiers as a sign of disrespect. Clara Barton, who would become famous for starting the Red Cross, was one of the nurses who tended to the men. Sergeant Carney, whose father had been a slave, managed to plant the flag on Wagner’s parapet after snatching it from fallen Color Sergeant John Walls and despite several wounds, brought it back to the rear, refusing to relinquish it to anyone and proudly proclaiming, “The old flag never touched the ground, boys.”[14] He received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his courage. Two of the captains, friends in life, died together according to a witness. One of the 54th reported piles and rows of soldiers, some alive and missing limbs and some dead. Companies that were not in battle served as stretcher-bearers, as did the musicians.

Northern newspapers carried stories about the bravery of the 54th under fire and because of their courage, many were forced to reevaluate their racist views of African American soldiers. A few of the men received promotions to rank of officer, including Black chaplain Reverend Samuel Harrison. Captain Luis Emilio, at age nineteen, was the only officer able to command following battle until a new colonel was in place. It was one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War but when the hospitalized men were asked if they would fight again, all responded that they would, even if missing a limb or severely wounded.

Following the failure of the Union to take Fort Wagner, those in charge of the siege began to lay blame on those who made mistakes. It was clear that reinforcements were not ordered to back up the 54th and the initial attackers. The 10th Connecticut did not relieve them until approximately 2:00 a.m., eight hours after the battle began. There seemed to be a lack of planning, faulty intelligence, no available visual plan, and no instructions on how to storm a fort. General Quincy Gillmore was in charge of the siege, so those mistakes, as well as others, must ultimately be attributed to him.

In August, following the battle at Fort Wagner, the 54th was assigned to work details in preparation for a second attack. When the payday of August 8 arrived, the men refused their pay once more. Besides being under fire from the Rebels, the men also were worried about the status of their captured brothers, who because they were Black could be charged with capital crimes. According to Confederate War Department General Order No. 60, issued on August 1, 1862 and extended by President Jefferson Davis a few months later, captured Black soldiers “should not be regarded as prisoners of war and should be turned over to state authorities and treated in accordance with the laws of the state in which they had been taken prisoner.” That order meant that Black troops could be executed.[15] On September 8, the Union troops finally occupied Fort Wagner after a fifty-eight-day assault because the Confederates evacuated it, as well as Fort Gregg.[16] There was a Rebel attempt to blow up the fort but their fuses were defective.

By late January 1864, the 54th was placed under the command of Colonel Montgomery as part of Brigadier General Truman Seymour’s Florida campaign. In February, they would make a name for themselves again in the Battle of Olustee (Ocean Pond).[17] At that time, Florida was strategically important to the Confederates because of its extensive railroad system and its cattle industry that supplied Southern troops. If it were not for the Black troops, the 54th and two other units, the Union soldiers might have been totally defeated. Confederate Brigadier General Joseph Finegan was the victor and almost routed the Union troops, but the 54th held its line, which allowed Union troops to escape with a casualty rate of 36-percent, about twice that of the Rebels.[18] The Massachusetts soldiers received more praise in Northern newspapers. General Seymour received the blame for the mission’s failure and was reassigned. The 54th then proceeded to Jacksonville, where they remained until April 1864.

Again, Morris and James Islands became the home of the 54th. On September 28, 1864, the men finally received their equal pay of $13 a month, not the discriminatory $10 a month.[19] Their families, which had been suffering financially, received about two-thirds of the amount of cash paid to them. Two months later, they were on to their next campaign at Honey Hill, South Carolina, where again they would exhibit pride and bravery. Under Colonel Henry Northey Hooper, they became part of General John Porter Hatch’s Department of South, providing a foothold for Major General William Tecumseh Sherman.[20] Again part of a Union failure, the 54th and its sister Massachusetts unit, the 55th, formed a line between the Confederates and the retreating Union troops, allowing for the evacuation of wounded soldiers.

There were some skirmishes as the unit moved toward Charleston, South Carolina, entering that city on February 27, 1865, behind the first Union troops.[21] Both the 54th and the 55th broke into slave pens and freed slaves. Of course, White Charlestonians resented their presence. They had to camp in a cemetery, but served with pride. Battles and skirmishes continued in South Carolina with Confederate trains being captured and burned, mills and products destroyed, slaves freed, and other successful actions taken at Boykin’s Mills until March 21. In early April the 54th moved toward Camden, South Carolina, to join Brigadier General Edward Elmer Potter in what would be dubbed “Potter’s Raid.” The skirmishes would continue until they arrived and occupied Camden in mid-April.[22] They and the rest of Potter’s brigade marched and skirmished to Manning, South Carolina, arriving on April 8, and arrived at Sumterville the following day, where they destroyed three locomotive and thirty-five cars.[23] They did not know about the surrender at Appomattox or the death of President Lincoln.

The men continued to perform guard duty and garrison duty after reaching Charleston on May 6. They were attached to the District of Charleston, Department of the South, where they remained until August, after which they traveled to Boston for their muster-out ceremony.[24] After their discharge on September 2, the 54th marched through Boston to the State House, where Governor Andrew and Bostonians greeted them with cheers.

Boston remembered the 54th on May 31, 1897, with the unveiling and dedication of the Shaw Memorial. Although official guests at the ceremony included the governor of Massachusetts, Boston’s mayor and the unit’s White officers, none of the attending sixty-five Black veterans received an invitation to sit in the seats of honor.[25] With each passing year the recollections of the 54th receded from the nation’s collective memory until the 1989 film Glory, which saw a surge of interest in the Massachusetts 54th and other Black units of the Civil War.

And ages yet uncrossed with life,

As sacred urns, do hold each mound

Where sleep the loyal, true, and brave

In freedom’s consecrated ground.[26]

- [1] Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, “The Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth,” Weekly Anglo-African, 10 October 1863, quoted in David Yacovone, “Sacred Land Regained: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and ‘The Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth,’ A Lost Poem,” Pennsylvania History 62, no. 1 (Winter 1995): 106.

- [2] The Emancipation Proclamation. http://www.nps.gov/ncro/anti/emancipation.html (Accessed July 4, 2014).

- [3] P. C. Headley, Massachusetts in the Rebellion: A Record of the Historical Position of the Commonwealth and the Services of the Leading Statesmen, the Military, the Colleges, and the People, in the Civil War of 1861-65 (Boston: Walker, Fuller, 1866), 450.

- [4] Luis F. Emilio, A Brave Black Regiment: History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863-1865 (New York: Johnson Reprint Company, 1968), 391.

- [5] Russell Duncan, ed., Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1992), 31-33.

- [6] Edwin S. Redkey, “Black Chaplains in the Union Army,” Civil War History 33 (December 1987): 332-5.

- [7] George H. Junne, Jr., A History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Colored Infantry of the Civil War (Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2012), 255-8.

- [8] Emilio, A Brave Black Regiment, 36-37.

- [9] Susan Spano, “America’s Best Small Town: Beaufort, SC,” Smithsonian (April 2014): 48.

- [10] Junne, Jr., History of the Fifty-Fourth, 286-8.

- [11] Joseph T. Glatthaar, Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers (New York: The Free Press, 1990), 136.

- [12] Emilio, A Brave Black Regiment, 73.

- [13] Carl J. Cruz, “Sergeant William H. Carney: Civil War Hero,” in It Wasn’t in Her Lifetime, But It Was Handed Down: Four Black Oral Histories of Massachusetts, ed. Eleanor Wachs (Columbia Point: Office of the Massachusetts Secretary of State, 1989), 7-8.

- [14] Ibid., 9-12.

- [15] Joe H. Mays, Black Americans and Their Contributions Toward Union Victory in the American Civil War, 1861-1865 (Lanham: University Press on America, 1984), 30.

- [16] “Fall of Fort Wagner,” New York Daily Tribune, September 11, 1863.

- [17] Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Massachusetts in the Army and Navy During the War of 1861-65 (Boston: Wright and Potter Printing Company, 1896), 461.

- [18] William H. Nulty, Confederate Florida: The Road to Olustee (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1990), 165, 203, 211

- [19] James L. Bowen, Massachusetts in the War, 1861-1865 (Springfield, MA: Clark W. Bryon, 1889), 678.

- [20] Christian A. Fleetwood, The Negro as a Soldier (Washington, DC: Howard University, 1895), 13.

- [21] Bowen, Massachusetts in the War, 680.

- [22] Junne, History of the Fifty-Fourth, 502.

- [23] W. N. Collins “Account of Potter’s Raid.” http://vcwsg.com/PDF%20Files/A%20BRIEF%20HISTORICAL%20BACKGROUND%20OF%20POTTERS%20RAID.pdf (Accessed July 4, 2014).

- [24] Bowen, Massachusetts in the War, 681.

- [25] Junne, History of the Fifty-Fourth, 566-8.

- [26] Harper, “The Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth.”

If you can read only one book:

Junne, Jr., Dr. George H. A History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Colored Infantry of the Civil War. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2012.

Books:

Blatt, Martin H., et al. Hope and Glory: Essays on the Legacy of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. Baltimore, MD: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001.

Burchard, Peter. One Gallant Rush, Robert Gould Shaw and his Brave Black Regiment. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1965.

Cornish, Dudley Taylor. The Sable Arm: Negro Troops in the Union Army, 1861-1865. New York: Longmans, 1956.

Duncan, Russell, ed. Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1992.

———. Where Death and Glory Meet: Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999.

Emilio, Luis F. A Brave Black Regiment or The History of the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment. Boston: Boston Book Company, 1891.

Gladstone, William A. United States Colored Troops, 1863-1867. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1990.

———. Men of Color. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1993.

Glatthaar, Joseph T. Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers. New York: The Free Press, 1990.

Gooding, James Henry. On the Altar of Freedom: A Black Soldier’s Civil War Letters from the Front. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1991.

Greene, Robert Ewell, Swamp Angels: A Biographical Study of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, True Facts About the Black Defenders of the Civil War. Bomark/Greene Publishing Group, 1990.

Luck, Wilbert H. Journey to Honey Hill: The 55th Massachusetts Regiment’s (Colored) Journey South to Fight the Civil War that Toppled the Institutions of Slavery. Washington D.C.: Wiluk Press, 1976.

Massachusetts Adjutant Generals Office. Record of Massachusetts Volunteers, 1861-1865. Boston: The Adjutant-General under a resolve of the General Court, 1868-1870.

McPherson, James M. The Negro’s Civil War: How American Negroes Felt and Acted During the War for the Union. New York: Pantheon, 1965.

Pearson, John Greenleaf. The Life of John A. Andrew: Governor of Massachusetts 1861-1865, 2 vols. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1904.

Quarles, Benjamin. The Negro in the Civil War. Boston: Little Brown, 1953.

Schouler, William. A History of Massachusetts in the Civil War, 2 vols. Boston: E.P. Dutton, 1868-1871.

Teamoh, Robert T. Sketch of the Life and Death of Col. Robert Gould Shaw. Boston: Grandison & Son, 1904.

Vierow, Wendy. The Assault on Fort Wagner: Black Soldiers Make a Stand in South Carolina Battle. New York: Powerkids Press (Rosen Publishing), 2004.

Werstein, Irving. The Storming of Fort Wagner. New York: Firebird Books/Scholastic Press, 1970.

Wilder, Burt G. The Fifty-Fourth Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Colored: June1863-September 1865. 3rd ed. Brookline, MA: The Riverdale Press 1919.

Williams, George W. A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865 Preceded by a Review of the Military Services of Negroes in the Ancient and Modern Times. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1888.

Organizations:

The 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

The 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment was reactivated on November 21, 2008 to serve as the Massachusetts National Guard ceremonial unit to render military honors at funerals and state functions. The new unit is now known as the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment Massachusetts National Guard Ceremonial Unit.

B Company 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment

B Company 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment is a re-enactor group dedicated to preserving the history of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment and Black soldiers in the Civil War.

Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

The Gilder Lehrman Institute contains primary and secondary resources for the history of the Massachusetts 54th.

Massachusetts Historical Society

The Massachusetts Historical Society offers, workshops and programs and primary source archives relating to the 54th Massachusetts.

National Archives at Boston

The National Archives at Boston has primary source material on the 54th Massachusetts including letters, reports, and records.

Web Resources:

Ric Oliveira, “Valor of 54th”, South Coast Today, February 13, 1999.

Benjamin F. Payton, Speech at the Centennial Celebration of the Monument to Robert Gould Shaw and the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment.

Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Infantry is a website containing a number of useful links to primary sources and related websites relating to the regiment.

This historynet.com website contains a short history of the 54th Massachusetts.

This blackpast.org website contains a short history of the 54th Massachusetts.

The Civil War Trust page on Robert Gould Shaw is located at this URL.

This is the National Park Service page covering the Shaw and Shaw Memorial in Boston MA.

This website contains useful links to primary and secondary sources on Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts.

This website contains letters written to and from soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts and links to archives with additional letters.

This is a lesson plan for teaching the history of the 54th Massachusetts.

Other Sources:

African American Civil War Memorial and Museum

The Museum is dedicated to the history of African Americans in the Civil War. It is located at 1925 Vermont Ave. NW, Washington DC 20001. 202-667-2667. It is open T-F 10:00 a.m. to 6:30 p.m., Sat 10:00 a.m.; to 4:00 p.m., Sun noon to 4:00 p.m.The Massachusetts 54th

American Experience video available from PBSGlory

Glory is a 1989 Film about the 54th and the assault on Fort Wagner directed by Edward Zwick and starring Matthew Broderick, Denzel Washington and Morgan Freeman among others.