Confederate Nationalism

by Paul Quigley

Confederate nationalism gave Confederates a coherent set of ideas to explain and justify their independence.

In Montgomery, Alabama in February, 1861, delegates from the lower tier of southern states signed the provisional Confederate Constitution and thereby created a new, independent nation-state. Much more difficult, though, would be the creation of Confederate nationalism. Confederates needed a coherent set of ideas to explain and justify their independence to themselves, to their erstwhile compatriots to the north, and to the rest of the world. Only nationalism could fully validate their status as an independent country. Over the next four years, even as they were struggling to win their independence on the battlefield, Confederates also paid much attention to the questions of what made them a distinctive people and why their distinctiveness should merit political independence.

Ever since the Civil War, Confederate nationalism has been a controversial subject. The fact that the Confederates’ bid for independence failed has made many commentators unwilling to take its nationalism seriously. They have assumed that if there really was a Confederate nationalism worth talking about, the Confederacy would surely have won the war and established its independence. Furthermore, because the raison d'être of the whole undertaking was slavery, and because slavery has had few outright defenders since 1865, paying attention to Confederate nationalism has often seemed distasteful. But in recent years historians have begun to take Confederate nationalism more seriously. Instead of instinctively assuming that it must have been either non-existent or spurious, historians such as Drew Gilpin Faust have begun “to explore Confederate nationalism in its own terms—as the South’s commentary upon itself—as its effort to represent southern culture to the world at large, to history, and perhaps most revealingly, to its own people.”[1]

Confederate nationalism did not properly exist until the creation of the Confederacy as a political entity in 1861. Yet it did build on important prewar foundations: first, the southern regional identity that had grown throughout the antebellum conflict over slavery; second, and somewhat paradoxically, the strong commitment to American nationalism that most white southerners shared until the secession winter of 1860-61.

Southern identity emerged gradually during the decades between the American Revolution and the Civil War. Factors such as climate, geography, economic development, and cultural values combined to imbue the region’s inhabitants with a sense of difference from northerners. But the factor that underpinned these sources of distinctiveness—the one thing that set the South apart more than anything else—was the institution of slavery. As the northern states gradually abandoned slavery following the American Revolution, the southern states’ dependence upon it only increased. It was first and foremost an economic institution. But it gave rise to a distinctive set of political values, a distinctive set of social relationships not only between white and black southerners but also between different classes of white people, and distinctive cultural beliefs and behavioral patterns. All of this combined to create a powerful sense of southern identity, and to drive white southern leaders into recurrent political conflicts with the North.

For most of the antebellum period, most southern leaders had been content for southern identity to coexist in relative harmony with the broader American national identity. They had been content to advance southern interests within, rather than outside of, the United States. But a small number of prominent southerners went further, advocating for southern independence outside the United States. These antebellum southern nationalists—men such as Robert Barnwell Rhett of South Carolina, William Lowndes Yancey of Alabama, and Edmund Ruffin of Virginia—believed that northerners had become so hostile to southern interests that national independence was necessary. Writers like South Carolina’s William Gilmore Simms used their pens in an effort to establish the appeal of southern nationhood, while politicians advanced the argument in the political arena.

Still, secessionists were in a minority right up to the eve of the Civil War. The large majority of white southerners, even as they embraced a southern regional identity, and even as they engaged in political conflict with the North, were fervent American nationalists. They celebrated the Fourth of July in the same way as northerners did: with parades, speeches, prayers, and banquets. They honored the American flag. They enthusiastically supported the United States in the Mexican War. They held a high opinion of America’s role in global history, seeing their country as a beacon of liberty and democracy as well as a model of Christianity. They proudly cherished their identities as Americans.

Because white southerners had been such enthusiastic American nationalists, U.S. symbols and history would rank among the most important ingredients of the new Confederate nationalism that began to emerge in 1861. The heroes of Confederate nationalism were by and large the same revolutionary heroes that all Americans venerated, with George Washington towering above them all. White southerners cherished much the same history as Confederates that they had done as Americans: the history of colonial settlement, of revolutionary liberation, of America’s historic commitment to freedom. The Confederacy’s first national flag, the “stars and bars” bore a strong resemblance to the “stars and stripes.” Confederates also defined their national purpose in familiar terms, presenting the new nation as a means to advance the ideals of liberty and democracy.

Confederate nationalism was not an exact replica of American nationalism, however. It is symptomatic that the Confederate founders mostly replicated the U.S. Constitution, but that one of the few changes they made was explicit protection for slavery. As had been the case with antebellum southern identity, more than any other factor it was the peculiar institution that made the Confederacy unique. Confederate vice-president Alexander Stephens made this explicit in his well-known “cornerstone” speech of March, 1861, in which he declared that the Confederacy’s “foundations were laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and moral condition.” Yet even though slavery was the sine qua non of Confederate nationalism, it was not its only ingredient. On the contrary, Confederates worked hard throughout the war to create and publicize a national identity with many dimensions.[2]

Ethnicity, for one thing, was widely recognized in the nineteenth-century world as being a vital component of nationalism. One of the most effective ways of proving that a group of people constituted a genuine nation was by appealing to their ethnic background. Thus some southern writers rooted the North-South conflict in the Cavalier-Roundhead opposition of the English Civil War, arguing that descendants of the Cavaliers had settled in the American South and descendants of the Roundheads in the North. This was a fairly common idea. Other authors claimed that North-South ethnic distinctions stretched back even further, all the way back to the French invasion of England in 1066. Thus one periodical article in 1861 claimed that the Anglo-Saxons had dominated in the settlement of New England, while “the Norman—chivalrous, impetuous, and ever noble and brave—attained its full development in Cavaliers of Virginia, and the Huguenots of South Carolina and Florida.” Although such claims lacked convincing substance, they were clearly meaningful to contemporaries, and represented an important strand of Confederate nationalism.[3]

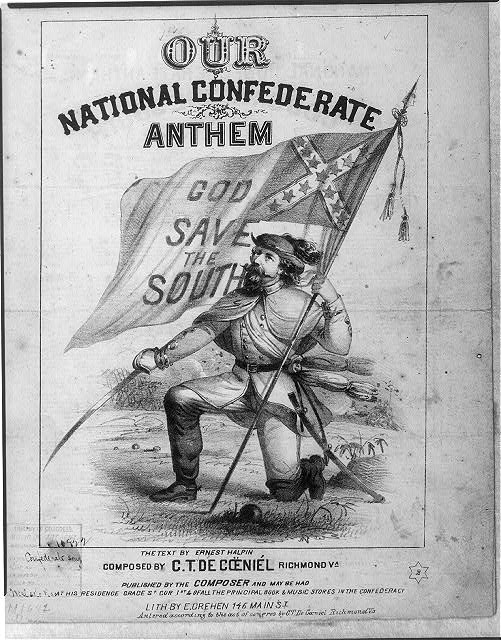

Like ethnicity, literature was a central component of nationalism across the nineteenth-century world. Here too, Confederates strived—albeit with limited success—to fit the global template. Even before the war, writers like William Gilmore Simms and Alexander Beaufort Meek had used their writing to advance the idea of southern distinctiveness. After secession and the creation of the Confederacy, southern authors were even more committed to using their writings to strengthen and substantiate Confederate nationalism. Even while they were fighting a virtually all-encompassing war, they managed to publish an impressive array of books, articles, plays, textbooks, poems, and other items. The Charleston Mercury explained the nationalist stakes of this impulse with its exhortation, “Let our writers write, as our soldiers fight, and our people cheer both parties, whether wielding sword or pen.” Although the quality of Confederates’ literary output was mixed, these kinds of exhortations undeniably reinforced the South’s attempt at cultural as well as political independence.[4]

As has been the case with so many national groups across the modern world, Confederates defined themselves as much by saying what they were not as by saying what they were. Anne Sarah Rubin has shown that there were two negative reference points against which Confederates defined themselves: the internal “other” of the black slave and the external “other” of the Yankee. Both practices had prewar roots. Dating back to the revolutionary and even the colonial era, white southerners had rested their developing sense of identity upon their differences from enslaved African Americans. White equality, freedom, democracy, and identity were all made possible by the denial of those opportunities to African Americans. At the same time, southern regional identity emerged more than anything else out of the conflict with the North. Beginning to some degree with the constitutional debates, but even more so with the Missouri crisis of 1819-1820, northerners and southerners periodically came into political conflict over the question of slavery’s place in America’s future. The struggle sharpened a burgeoning sense of southern regional identity, as partisans on both sides painted the other side in an unfavorable light, questioning not only their political agendas but also their morals. Negative images of northerners became even more embittered and even more consequential in the South after secession. Southern discourse portrayed Yankees as liars, cheats, cowards, mammon-worshipping fiends with flawed ideas about everything ranging from humane warfare to the rightful place of women in civilized society. Every insult hurled northward served to consolidate southerners’ sense of themselves as a unique and a superior people.[5]

The idea of a civilized Confederacy doing battle with a savage Union also drew on the religious dimension of Confederate nationalism. Here was another area in which Confederate thought drew heavily on American traditions. The concept of the “chosen people” has underpinned many nationalisms around the world, and it certainly figured prominently in American identity, even before the United States existed. Like earlier generations of Americans, Confederates often imagined themselves to be God’s people fighting a divine fight. Even military defeats could be interpreted as signs that God was testing his “chosen people” in a divine trial. The religious perspective also helped Confederates to deal with the countless deaths that came along with any military engagement, whether victory or defeat. The fallen soldiers were frequently held up as martyrs who had sacrificed their lives for a noble and a sacred cause. The celebration of nationalist death sacrifice helped connect surviving Confederates together, imbued the war effort with a spiritual transcendence, and embedded the Confederate nation in a nationalist continuum that linked the present generation with the past and the future.

The celebration of battlefield victories and military heroes had an enormous impact on Confederate morale. As Gary Gallagher has reminded us, military fortunes and military symbols were crucial ingredients of Confederate identity. As Confederates well knew, their experiment in nation-making would stand or fall on the battlefield. And so they anxiously followed news from the front—fronts, more accurately—and lionized the generals and the armies who secured Confederate victories. There were no national symbols more potent than the figure of Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. Lee became a stronger figurehead than any other leader, including President Jefferson Davis; more than anyone else, he became synonymous with the Confederate nation itself.[6]

Because the Confederacy was at war for just about its entire history, its identity was heavily imbued with militaristic and therefore masculine symbolism. Confederates often described their national purpose in terms of brave and noble men protecting their homes, women, and children from the northern menace. The most common portrayal of women’s role in Confederate nationalism was as loyal supporters of their men. Hence the countless images of women stoically waving handkerchiefs as their husbands, sons, and fathers went off to war. Yet although those images were certainly based in reality, many women also played more active roles in the development of Confederate nationalism. As has been true in many modern wars, the practical demands of intensive conflict afforded women opportunities to participate in public discussion about the war effort and the nature of the Confederacy, and to forge relationships with the national government that would not have been possible in peacetime.

Not every resident of the Confederate States wanted to see the Confederate nation-state succeed. Many African Americans recognized that it was not in their interests for the Confederacy to succeed, and that the only roles they would be permitted to play in Confederate nationalism were subservient ones. Taking advantage of the opportunities offered by the crisis of war, black southerners were active participants in the redefinition of U.S. much more than Confederate national identity and citizenship.

Even among white southerners, there was hardly unanimity over the meaning of Confederate nationalism, or even over the question of whether the Confederacy ought to exist at all. There were many varieties of dissent in the Confederacy. Some southerners, found most commonly in mountainous regions of the country such as western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, and northern Alabama, did not want the Confederacy to exist at all. Some of these southern unionists fought actively for the Union war effort, many more quietly acceded to secession and the creation of the Confederacy. But not all dissenters repudiated the Confederacy altogether. It was more common to disagree with specific government policies than with the whole undertaking; to be more interested in redefining Confederate nationalism than in rejecting it altogether. Many deserters, for example, fell into this category. Soldiers often made the decision to desert more because of a need to help struggling families at home than because they disagreed with the Confederate cause in its entirety.

Confederate nationalism did not only take shape in a domestic context. In crafting their own national identity, Confederates drew on international, especially transatlantic ideas about what made a nation a nation. They also attempted to persuade the rest of the world that their national status was deserved. After all, a nation-state needed the approval of the international community if it were to achieve legitimacy. Accordingly, the Confederacy launched a diplomatic initiative at the very outset of its existence in 1861. Targeting Britain in particular, and to a lesser extent other European countries such as France, Confederate diplomats made their case. They appealed to European self-interest, citing King Cotton as the primary reason why they should be recognized. They also made the constitutional argument that the U.S. had been created as a confederation, and members were free to come and go at will. But they also endeavored to prove that they possessed a genuine nationalism, pointing to their differences from northerners to persuade Europeans that they really did represent a distinctive people that deserved national independence.

Confederates failed to convince European governments that they had in fact built a legitimate nation-state. They also failed to make that case where it mattered most of all: on the battlefield. Yet that does not mean that Confederate nationalism did not exist. For four years, Confederates strived to define a new nationalism. Like all nationalisms, it was more a conversation-in-progress than a finished product. It was always the subject of internal contention. It was a nationalism that came into being because of the North-South disagreement over slavery’s future, but one that came to be based on much more than the defense of slavery alone. It was a nationalism that had deep roots in American symbols and values, but that also derived great strength from deepening contrasts with the North. It was a nationalism that based its prospects for survival on the fortunes of its revered military heroes. Ironically, just as failure in the war ended Confederates’ dreams of legitimate nation-state status, that same failure would go on to spawn an even more powerful white southern identity based on the shared experience of defeat and the memory of a Lost Cause.

- [1] Drew Gilpin Faust, The Creation of Confederate Nationalism: Ideology and Identity in the Civil War South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988), 6-7.

- [2] Reprinted in The Civil War Archive: The History of the Civil War in Documents, ed. Henry Steele Commager, revised by Erik Bruun (New York: Black Dog & Leventhal, 2000), 566-67.

- [3] “The Conflict of Northern and Southern Races,” De Bow’s Review 31:4-5 (Oct-Nov 1861), 393.

- [4] Charleston Mercury, May 16, 1861.

- [5] Anne S. Rubin, A Shattered Nation: The Rise and Fall of the Confederacy, 1861-1868 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

- [6] Gary Gallagher, The Confederate War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997).

If you can read only one book:

Quigley, Paul. Shifting Grounds: Nationalism and the American South, 1848-1865. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Books:

Beringer, Richard, et al. Why the South Lost the Civil War. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986.

Bernath, Michael T. Confederate Minds: The Struggle for Intellectual Independence in the Civil War South. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Berry, Stephen. All That Makes a Man?: Love and Ambition in the Civil War South. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Binnington, Ian. “‘They Have Made a Nation’: Confederates and the Creation of Confederate Nationalism.” Ph.D. diss., University of Illinois, University Library, 2004.

Blair, William. Virginia’s Private War?: Feeding Body and Soul in the Confederacy, 1861-1865. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Bonner, Robert. Colors and Blood: Flag Passions of the Confederate South. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

_____. Mastering America?: Southern Slaveholders and the Crisis of American Nationhood. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Mastering America?: Southern Slaveholders and the Crisis of American Nationhood. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009. Patriotic Envelopes of the Civil War: The Iconography of Union and Confederate Covers. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010.

Browning, Judkin. Shifting Loyalties: The Union Occupation of Eastern North Carolina. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Bynum, Victoria. The Long Shadow of the Civil War: Southern Dissent and Its Legacies. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Carmichael, Peter S. The Last Generation: Young Virginians in Peace, War, and Reunion. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Cauthen, Melvin Bruce Jr. “Confederate and Afrikaner Nationalism: Myth, Identity, and Gender in Comparative Perspective.” PhD thesis, University of London, UCL Library, 2000.

Crofts, Daniel. Reluctant Confederates?: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

Degler, Carl N. The Other South: Southern Dissenters in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

Doyle, Don. Nations Divided?: America, Italy, and the Southern Question. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002.

Escott, Paul. After Secession?: Jefferson Davis and the Failure of Confederate Nationalism. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.

Faust, Drew Gilpin. The Creation of Confederate Nationalism: Ideology and Identity in the Civil War South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.

Fleche, Andre. The Revolution of 1861?: the American Civil War in the Age of Nationalist Conflict. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Freehling, William. The South Vs. the South?: How anti-Confederate Southerners Shaped the Course of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Gallagher, Gary W. The Confederate War. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Garrett, Lynette A. “Confederate Nationalism in Georgia, Louisiana, and Virginia during the American Civil War, 1861-1865.” PhD diss., American University, 2012.

Gordon, Lesley, and John C. Inscoe, eds. Inside the Confederate Nation: Essays in Honor of Emory M. Thomas. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Inscoe, John, and Robert C. Kenzer, eds. Enemies of the Country?: New Perspectives on Unionists in the Civil War South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001.

Armitage, David, et al. “Interchange: Nationalism and Internationalism in the Era of the Civil War.” in Journal of American History 98, no.2 (September 2011): 455-489.

Manning, Chandra. What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007.

McCurry, Stephanie. Confederate Reckoning?: Power and Politics in the Civil War South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

McPherson, James. For Cause and Comrades?: Why Men Fought in the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

_____. Is Blood Thicker Than Water? Crises of Nationalism in the Modern World. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 1998.

Onuf, Nicholas Greenwood, and Peter Onuf. Nations, Markets, and War: Modern History and the American Civil War. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006.

Osterweis, Rollin. Romanticism and Nationalism in the Old South. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1949.

Potter, David M. “The Historian’s Use of Nationalism and Vice Versa.” American Historical Review 67, no.4 (July 1962): 924–950.

Rable, George C. Civil Wars: Women and the Crisis of Southern Nationalism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

_____. The Confederate Republic: A Revolution Against Politics. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Roberts, Timothy Mason. Distant Revolutions: 1848 and the Challenge to American Exceptionalism. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009.

Rubin, Anne S. A Shattered Nation: The Rise and Fall of the Confederacy, 1861-1868. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Ruminski, Jarret. “Southern Pride and Yankee Presence: The Limits of Confederate Loyalty in Civil War Mississippi, 1860-1865.” PhD diss., University of Calgary, 2012.

Storey, Margaret M. Loyalty and Loss: Alabama's Unionists in the Civil War and Reconstruction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004.

Sutherland, Daniel. Guerrillas, Unionists, and Violence on the Confederate Home Front. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Taylor, Amy. The Divided Family in Civil War America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Thomas, Emory. The Confederacy as a Revolutionary Experience. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1970.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

Documenting the American South is a digital publishing initiative that provides Internet access to texts, images, and audio files related to southern history, literature, and culture sponsored by The University Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The "Confederate Broadside Poetry Collection" at Wake Forest University consists of over 250 examples of poems written by Southerners and Confederate sympathizers during the Civil War. The collection includes some pamphlets and clippings, as well as broadsides.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.