Desertion, Cowardice and Punishment

by Mark A. Weitz

An analysis of how both sides handled desertion and cowardice

The American Civil War brought an unprecedented increase in the size of armies in North America. From a small regular army of approximately 16,000 in 1860, the two sides put about three million men in the field during the course of the four-year conflict. Historians concede that exact numbers are unattainable, but estimates of total Confederates under arms is between 800,000 and 1,200,000. The Union army is estimated to have been slightly over 2 million men. Drawn from every corner of America, both armies were overwhelmingly volunteer forces comprised of men unfamiliar with war and the rigors of military life. Thus, in addition to the logistical challenges of training and equipping these armies, military and civilian officials faced the challenge of keeping the army intact, and throughout the war desertion posed a problem for both sides.

Defined as leaving the military with the intent not to return, desertion differs from cowardice. Cowardice in the civil war was defined as deserting in the face of the enemy. While deserters numbered in the hundreds of thousands, deserting in the face of the enemy was far less common a crime, or at least not as prominent in the records that survive. To be sure, the image of Henry Fleming fleeing the battlefield in Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage had its basis in historical fact and undoubtedly occurred. However, statistically Civil War soldiers spent fifty days in camp for every day of combat, and desertion was by far a camp phenomenon as opposed to a decision made in the heat of battle. Often cowardice in the face of the enemy was something observed by a soldier’s comrades, and even if never prosecuted, it tainted a man’s reputation for the remainder of his life if he was fortunate enough to survive the war. When prosecuted the penalty for cowardice could be harsh, with death by firing squad the most extreme sanction. Perhaps one of the reasons cowardice does not appear as often is that running in the face of the enemy often occurred on a unit-wide basis as some portion of the line became physically or morally overwhelmed and gave way. The subsequent retreat disintegrated into a wild, disorderly effort to escape slaughter. One man abandoning his post in such a manner would be cowardice; when it happened on a unit level it simply became a rout.

Desertion proved a far more difficult problem for both sides. Official figures show slightly over 103,000 Confederate soldiers and over 200,000 Union soldiers deserted, with some estimates as high as 280,000. New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio made up almost half of all Union desertions, and North Carolina and Virginia led the way among Confederate troops. Men deserted for a variety of reasons, many of which were common to both sides. The rigors or military life, poor food, inadequate clothing, homesickness, and concern for loved ones at home all drove men to desert. In some ways the character of the American soldier contributed to the desertion problem. Most men on both sides were unaccustomed to the rigid nature of being a soldier, and the loss of personal freedom that came with being in the military proved difficult. Many soldiers saw their enlistment as contractual in nature and any perception that the government was not living up to its end of the bargain justified their departure. This reliance on the government’s promise as a reason to desert would prove particularly troublesome for the Confederacy where soldiers believed their commitment to fight was based in part on the promise that their families would be taken care of in their absence.

Morale also played a part in desertion. Early defeat, particularly for the Union in the eastern theater, combined with the horrific nature of combat most certainly motivated men to desert. In addition camp life could be every bit as dangerous as battle. Two out of every three soldiers who died during the war fell victim to disease. Dysentery, or “Virginia Quickstep,” killed 45,000 men, and the recognition that camp life might be as dangerous as combat provided an incentive for men to desert. Finally, for some there was an element of coercion. The South began drafting soldiers in 1862 and the Union followed a year later. Even for those who volunteered, their one-year enlistments became three-year commitments, and for Southern soldiers the act of volunteering for a year eventually evolved into a commitment to remain for the duration of the war. But, while the causes and effects of desertion had elements common to both sides, many aspects of desertion were unique to one army or the other.

UNION DESERTION:

Desertion from the Union army began early in the war and continued to some degree throughout the conflict. Early enlistments were for three months, and volunteers flocked to the cause believing the rebellion would be suppressed in short order. When it became clear that subduing the Confederacy would be a much more arduous task, particularly in light of Union defeats in July, August, and October of 1861, the patriotic fervor that drove enlistment in the first months of the war began to wane and with it the commitment of some men to the cause. However, one aspect of enlistment unique to the Union army clearly contributed to desertion and appealed to men who never intended to remain in the service. The Union paid bounties, or enlistment bonuses for new recruits, often as much as $300.00. Men enlisted, collect their bounty, and then deserted. Thereafter, a deserter re-enlisted under a different name and at a different place, collected another bounty, and then deserted again. The Union Army paid privates an average salary of $13 per month. A $300 bounty amounted to almost twice a private’s annual salary and a man willing to test the bounty system multiple times could amass a tidy sum in a short period of time. Although the Confederacy also paid bounties, the money was far less than in the North, and as Confederate currency became less accepted, it offered far less of an incentive for a man to volunteer to leave home and family for the uncertainty of war.

Bounty jumpers tended to find their way to the North’s large urban areas. New York City for example served as home to as many as 3,000 bounty- jumping deserters, as men flush with money sought out the anonymity and the ability to blend into the crowd that large cities offered. Aside from the depletion of manpower, bounty jumping created a unique problem for the historian seeking to understand Union desertion. In most cases desertion numbers are derived from soldiers’ service documents that are now part of the Union and Confederate service records housed at the National Archives. Those records identify men by name and unit. If one man enlisted, deserted, and then re-enlisted under a different name, any subsequent desertion would reflect that a different man had deserted. In reality the same man may have deserted multiple times.

While Union desertion ran the full course of the war, there were periods when it spiked, most notably the winter and spring of 1863 in the wake of the Union army’s devastating defeat at Fredericksburg and its retreat following the Battle of Chancellorsville. The service records of Private Robert Montgomery, Company F, 91st Pennsylvania Infantry, provide a good example. In the thick of the fighting at Fredericksburg as part of Brigadier General Andrew Atkinson Humphreys’ assault at Marye’s Heights, Montgomery used his subsequent assignment after the Battle of Chancellorsville to slip away from the front and desert. Assigned to guard the baggage of his brigade commander at Aquia Landing, on May 16, 1863 Montgomery disappeared and was never found again. His final and successful desertion from the Union army ended his brief but eventful career as a soldier. He was promoted after his enlistment in 1861 only to be subsequently reduced in rank. In 1862 he unsuccessfully tried to desert only to be returned to the ranks. Although he did not see action at Antietam he was at both Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Montgomery had seen enough combat and had apparently lost any zeal he may have had for the cause.

Robert Montgomery took advantage of an opportunity that would diminish over time. As the North successfully invaded the South, particularly in the western theater, desertion did not present the easy opportunity to escape back into the relative safety of the Northern home front. By the beginning of 1863Major General Ulysses S. (Hiram Ulysses) Grant’s army had penetrated deep into Mississippi and by the end of the year moved to southern Tennessee to lift the siege at Chattanooga. Eventually under Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, that same army advanced south into Georgia and the Carolinas. Following the Battle of Gettysburg the Army of the Potomac crossed back into Virginia and the following spring began a campaign that took it to the gates of Richmond. Thus, as the war continued the opportunities to desert become less attractive.

Union desertion also demonstrated the degree to which the North struggled with an anti-war movement and the effect it had on soldier morale. Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton advocated executing deserters as an example in an effort to deter future desertion. Abraham Lincoln struggled with the notion that the army would shoot a man for deserting, yet the government remained powerless to punish those at home who openly advocated desertion and the abandonment of the war effort. Clement Laird Vallandingham and the Copperhead movement he led publicly encouraged Union soldiers to desert. Lincoln struggled with executing deserters, and the correspondence between himand Stanton shows Lincoln requesting and personally examining numerous files of convicted deserters condemned to death. Lincoln refused to allow a solder under 18 years old to be executed, and in most other cases he pardoned condemned soldiers.

While Union desertion posed a problem, it did not have the crippling effect on the Union war effort that the Confederacy experienced. Part of the reason lies in pure mathematics. When the war began the North’s population stood at slightly over 20,000,000. The South on the other hand had a little over 10,000,000. However, slaves made up 4.5 million of its population and did not contribute to the Confederate war effort, at least not as combat soldiers. While many did serve in non-combat rolls, the demographics alone made Confederate losses from desertion more significant.

CONFEDERATE DESERTION

The desertion of Confederate soldiers proved a far greater problem than Union desertion. Ella Lonn’s 1928 study[1] claims that Union desertion made up a higher percentage of the total enlisted soldiers. Her figures indicate one in seven Union soldiers deserted compared to one in nine Confederate soldiers. Lonn’s figures are based on Thomas Livermore’s estimate of slightly over 1.5 million men enlisting in the Union army. However, Livermore’s estimates were actually higher, and with more recent estimates of over 2 million enlisted, the estimate of Union desertion is about one in ten men. Regardless, Confederate desertion proved much more damning. Desertion depleted an army that needed every able-bodied man. Its effects were felt not only in terms of those who deserted the ranks, but also in the manpower and resources dedicated to chasing and recovering deserters. As the war progressed desertion also raised questions as to the strength of Confederate nationalism when duty to nation came into direct conflict with men’s obligations to home and family.

While many Southerners readily stepped up to fight for the new nation, in reality recruitment posed problems from the start. While there are numerous examples of volunteer units forming and training even before the war began almost every state experienced difficulty in raising the number of troops expected by the Confederate government. James Chestnut of South Carolina indicated that about half of the Palmetto State’s eligible young men answered the call in 1861. Those who enlisted did so believing in the government’s promise to provide for their families in their absence. They also enlisted knowing that not everyone had to enlist.

The South’s unique dependence on slavery raised concerns that a total depletion of the white male population could give rise to slave insurrection. The fifteen- and twenty-slave rules allowed planters with at least that number of slaves to exempt from service one white male, usually an overseer. This exemption was in addition to other exemptions from service that were not tied to slavery. Railroad workers, telegraph operators, miners and civil servants were examples of non-slavery related exemptions. Exemptions notwithstanding, some desertion occurred early in the war, but it did not start to become a problem until 1862. Confederate success on the battlefield coupled with the home front not experiencing the hardships brought on by the depletion of its male population, served to lessen some of the motives that might cause men to desert. However, as the war moved into its second year, a variety of factors combined to undermine the Confederacy’s ability to keep its army in the field.

Enlistment had not met expectations, and in April 1862 the Confederacy became the first side to resort to the draft. Under the threat of being drafted more men enlisted in February and March of 1862 because by doing so they preserved the ability to fight with men they knew in units organized on a local level. Thereafter the Confederate army relied predominately on men who had not been willing to join under any circumstances. At the same time the draft became a reality, the Confederate government unilaterally extended the one-year enlistments of 1861 into three-year commitments. Eventually the three-year commitments became obligations for the duration of the war. These wartime measures added an element of coercion to military service that did not exist in 1861.

As the Confederacy moved to bolster its army, events beyond its control increased the possibility of losing men to desertion. At the start of the war almost 84% of Southerners engaged in some form of agriculture, the vast majority falling in the yeoman farmer category. People farmed to survive and the family unit depended on all of its members to contribute. By the summer of 1862 the families of men who enlisted when the war began had been without some or all of their male workforce for a year, and although those at home continued to do what was necessary to survive, the task became more difficult. In addition, shortages began to occur in crucial necessities, salt in particular. A world without refrigeration depended on salt for meat preservation, and the South began to struggle to provide enough for both civilians and the army. As the home front began to experience hardship a key component of its soldiers’ willingness to enlist began to fail. Government officials from almost every Southern state had openly represented to the soldiers that those who remained at home would be provided for in the absence of their men. Soldier family relief programs, organized on both the state and county level, proved unable to meet the demands placed upon them. Not every region or state suffered at the same time, but as the home front began to feel the strain of war, women began writing to their fathers, husbands, and brothers bringing the reality of the hardships at home to those on the battlefield.

In the spring and summer of 1862 the Union took steps to take advantage of the situation. Over a year before Abraham Lincoln’s Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction marked the beginning of wartime reconstruction, the Union army implemented a program that induced Confederate soldiers to desert, and at the heart of its efforts was the swearing of an oath of allegiance to the Union. The Union offered any Confederate soldier who deserted and came into Union lines the opportunity to swear the oath of allegiance and return home. Part of the offer included transportation as far south as the Union occupied. As the Union moved deeper into the South, particularly in the western theater, this offer enabled soldiers from places in the Deep South to desert with a realistic chance of getting home safely. Desertion in the Confederacy came from both a “push and a pull.” Life as a soldier was far from ideal, but the rigors of military life alone and the specter of death in combat or in camp were often not enough to compel a man to risk capture and punishment, perhaps even death. The pull from home made the decision easier for some, but willingness alone was often insufficient. The Union hoped to provide the element of safety to Confederate soldiers contemplating desertion. By 1865 over 30,000 Confederate soldiers took this route out of the Confederate army.

Following the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, even General Robert E. Lee conceded that desertion had become so a severe that it threatened the Confederacy’s ability to wage war. The harm to the Confederacy’s war effort was difficult to ignore. Soldiers took not only themselves, but also their weapons out of the fray. At home, state governors resisted national efforts to recruit more troops insisting that men were needed to hunt deserters and protect the home front. In some areas of the South deserter bands preyed upon the local civilian population, making difficult conditions even harsher. When Lincoln announced his program of amnesty and wartime reconstruction in 1863, civilian oath swearing as a condition to wartime readmission into the Union made it harder to keep men fighting for a cause that appeared to some to be evaporating on the home front. If those at home were conceding the inevitable and swearing allegiance to the Union, why continue to fight?

The last sixteen months of the war saw desertion cripple an already depleted army. Sherman’s invasion of Georgia in the spring and summer of 1864 allowed the Union desertion program to operate in the northern part of the state as men deserted in the wake of the North’s successful march to Atlanta. Lieutenant General John Bell Hood’s ill-fated invasion into Tennessee late that year helped complete the deterioration of the Army of Tennessee, as many men who survived the twin disasters of Franklin and Nashville, Tennesseans in particular, chose not to accompany the army into the Carolinas. In the east the stalemate outside of Richmond and Petersburg marked the end of any sustained offensive efforts by Lee’s army. The siege that ensued made desertion much easier, and men took advantage of the opportunity. Both Union and Confederate records reflect a steady stream of Confederate deserters into Union lines over the course of the ten-month siege.

PUNISHMENT:

Perhaps one of the most difficult aspects of desertion for both North and South lay in how to discipline captured deserters. Early in the war leniency dominated the conduct of both armies. Confederate court-martial proceedings reflect a willingness to look at individual circumstances and see desertion, even when men traveled behind enemy lines, as only a temporary departure, or “absence without leave.” In reality only about 10% of those who deserted ever returned willingly despite a belief among many historians that most Confederates took only “French leave” and intended to return. Lincoln’s unwillingness to execute deserters frustrated Union efforts to deal with the problem. One story tells of Edwin Stanton sending an envelope with fifty-five deserter cases to Abraham Lincoln for his review, and Lincoln simply writing “pardoned” on the envelope and sending it back. Military service records on both sides reflect men that had been “recovered” from desertion.

Alternatives to execution varied. In 1861 Confederate laws allowed for flogging up to thirty-nine lashes and branding the convicted man with the letter “D.” Branding had been used in the pre-Civil War Union army as well. However, both sides abandoned the practice and the Confederate congress removed both flogging and branding as acceptable forms of punishment early in the war. Short of execution, soldiers could be incarcerated in the stockade and subjected to a variety of non-lethal punishments designed to humiliate the offender. Men could be forced to wear a wooden sign indicating they deserted or displayed cowardice. Being drummed out of the army, while available as a punishment alternative, also ran contrary to the goal of keeping men in the service and was seldom used for deserters. Another common punishment, wearing an iron ball and chain, not only served to shame the offender, but also made deserting more difficult if not impossible.

While both sides showed an early reluctance to execute deserters, court martial records indicate that death by firing squad became an accepted means of dealing with the problem. Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson authorized the execution of five deserters from two different divisions in August 1862. In Tennessee, General Braxton Bragg had Private Asa Lewis executed for leaving the army twice. Lewis left to attend to his ill mother, but Bragg proved unsympathetic to his plight. Coming at Christmastime, the execution actually dampened morale. Bragg’s decision reflected a belief that temporary absence had to be stopped. Soldiers could not simply choose when they wanted to be gone, and a revolving door of unauthorized departures could be as damaging as outright desertion. Lieutenant General James Longstreet conceded as much in September 1862 when the south invaded Maryland without over 7,000 men who had either deserted or left only to return when the fighting was over. Regardless of their intent, these men absented themselves when they were needed most.

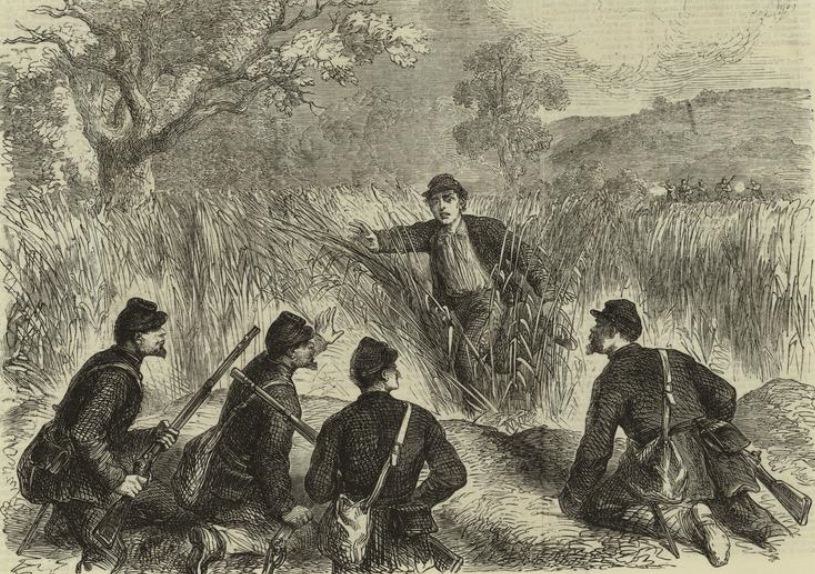

Even after both sides began executing deserters, less than 400 actually faced a firing squad in either army. However, soldiers’ diaries and letters reveal that when they occurred, executions had a sobering effect on those who witnessed the spectacle. Chaplain John R. W. Jewell of the 7th Indiana described an execution in Northern Virginia in 1863. With the entire division formed in a three –sided square, the convicted deserter marched to his place of execution, marked by a freshly dug grave next to which a crude coffin was placed. With drums slowly beating and a brass band playing a somber dirge, the company preacher administered some last words while the entire unit watched. When the preacher finished, the accused stood and faced a twelve-man firing squad, quietly allowed himself to be blindfolded, and awaited his fate. The accused did not wait long as the detail aimed and fired. Once the man’s death was confirmed the entire division marched past the body laid out on the ground next to the coffin. Not all executions were so formal, and the one described by Reverend Jewell indicates the degree to which the Union went to punish the crime. The executed man had been discovered in another unit where he had gone after deserting and re-enlisting and an officer in his former unit recognized him during company drill.

Confederate executions followed a similar script, and as the war progressed there are examples of multiple executions in some units on the same day. In the South Confederate soldiers also faced the added risk of being punished by Home Guards who patrolled counties unoccupied by the Union and would summarily execute deserters. However, even when execution became more common, some officers complained that the army failed to apply the penalty in a consistent manner. Lieutenant General Richard Taylor observed in 1864 that while men were executed in one unit, the same offense met with a far more lenient punishment in another unit within the same command. Aside from any shortcomings of the inconsistent application of the death penalty, by the time the Confederacy realized that desertion had to be punished severely, the problem had gone beyond the army’s ability to deter it.

- [1] Ella Lonn, Desertion During the Civil War. New York & London: The Century Company, 1928

If you can read only one book:

Mark A. Weitz, More Damning than Slaughter: Desertion in the Confederate Army. Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Books:

William Blair, Virginia’s Private War: Feeding Body and Soul in the Confederacy, 1861-1865. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Jack Bunch, Roster of the Courts Martial in the Confederate Armies. Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press, 2000.

Dora L. Costa and Matthew E. Kahn, Heroes and Cowards: The Social Face of War. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2008.

Ella Lonn, Desertion during the Civil War. Gloucester, Mass, American Historical Association, 1928.

Thomas P. Lowry, Confederate Death Sentences: A Guide. Charleston: South Carolina: Booksurge Publishing, 2009.

Bessie Martin, Desertion of Alabama Troops from the Confederate Army: A Study in Sectionalism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1932.

Mark A. Weitz, A Higher Duty: Desertion among Georgia Troops during the Civil War. Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

David Williams, Bitterly Divided: The South’s Inner Civil War. New York: New Press, 2008.

Peter S. Bearman, Desertion as Localism: Army Unit Solidarity and Group Norms in the U.S. Civil War. Social Forces, 70, December 1991.

Rand Dotson, “The Grave and Scandalous Evil Infected to your People”: The Erosion of Confederate Loyalty in Floyd County, Virginia. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 108, September 2000.

Lisa Laskin, “The Army is not near so much Demoralized as the Country is”: Soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia and the Confederate Home Front in Aaron Sheehan-Dean, ed., The View from the Ground: Experiences of Civil War Soldiers. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007.

Aaron W. Marrs, Desertion and Loyalty in the South Carolina Infantry, 1861-1865. Civil War History, 50, March 2004.

James T. Otten, Disloyalty in the Upper Districts of South Carolina during the Civil War. South Carolina Historical Magazine, 75, April 1974.

Trevor Plante, The Shady Side of the Family Tree: Civil War Union Court-Martial Files. Prologue Magazine, 30:4, Winter 1998.

Brian Holden Reid and John White, “A Mob of Stragglers and Cowards”: Desertion from the Union and Confederate Armies, 1861-1865. Journal of Strategic Studies, 8:1, 1985.

Richard Reid, A Test Case of the “Crying Evil”: Desertion among North Carolina Troops during the Civil War. North Carolina Historical Review, 58, July 1981.

Kevin Conley Ruffner, Civil War Desertion from a Black Belt Regiment: An Examination of the 44th Virginia Infantry in Edward L. Ayers and John C. Willis, eds., The Edge of the South: Life in Nineteenth-Century Virginia. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1991.

Mark Weitz, “I Shall Never Forget the Name of You”: The Home Front, Desertion, and Oath Swearing in Wartime Tennessee. Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Spring 2000.

NOTE ON SOURCES: The reader will immediately notice that there is far more scholarly work on the subject of Confederate desertion than its Union counterpart. Ella Lonn’s 1928 work is the only monograph that addresses Union desertion in any depth. There are three book length studies of Confederate desertion in addition to a variety of journal articles. The articles however tend for the most part to focus on Virginia and North Carolina. The imbalance in the literature reflects in some way the notion that desertion hurt the Confederacy far more than the Union and thus the story is somehow more important. That may not be the case. Lonn argued in her study that Union desertion may have prolonged the war by preventing the North from bringing even more overwhelming numbers to bear on the Confederacy. While it is difficult to argue with the many ways that desertion undermined the Southern war effort, a study of Northern desertion and its real impact on the war would be a welcomed addition to the growing, but nevertheless sparse literature on the subject of Civil War desertion.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.