Fort Pillow

by John V. Cimprich

Confederates created Fort Pillow, starting in the summer of 1861, on a high bluff above the Mississippi River about fifty miles north of Memphis, Tennessee. After the fall of Island No. 10, Fort Pillow became the front line on the river. On April 13, 1862, a Federal flotilla appeared under the command of Captain Andrew Hull Foote, and hostilities were commenced. Fighting continued on and off until Confederate Brigadier General John B. Villepigue successfully hid withdrawal from the fort on June 4, 1862. The fort was then garrisoned by union soldiers until January 21, 1864, when Major General William Tecumseh Sherman had it closed. Ignoring this, General Stephen H. Hurlbut reopened it on February 8 to protect local unionists and revive trade. He built up a garrison of 600, half black and half white troops. In mid-March Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest launched a raid through Western Tennessee and Kentucky. On April 12, 1864 at dawn 1,500 of Forrest’s men attacked the Fort Pillow garrison. At 2:00 p.m. Forrest called a truce and asked the Federals to surrender. He offered to accept the entire enemy force as prisoners, a generous stand as the Confederacy officially would have black troops either returned to owners or executed as rebellious slaves. He added that “Should my demand be refused, I cannot be responsible for the fate of your command.” The offer was refused and at 3:15 p.m. the Confederates charged and routed the Federals who fled down the bluff and became trapped against the river. Here the massacre began. According to one Confederate, “The slaughter was awful. Words cannot describe the scene. The poor deluded negroes would run up to our men fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands would scream for mercy but they were ordered to their feet and shot down. The whitte [sic] men fared but little better. Their fort turned out to be a great slaughter pen. Blood, human blood stood about in pools and brains could have been gathered up in any quantity.” Some Confederates claimed Forrest ordered the massacre. If Forrest made such an order in impulsive anger after the charge, he soon changed his mind. After the charge he rode into the inner fort, eventually ordered the massacre stopped, and even shot one soldier who ignored him. Several black artillerymen, like Samuel Green, would state that “If it had not been for General Forrest coming up and ordering the Confederates to stop killing the prisoners, there would not one of us been alive today.” The debate over what happened has continued ever since then, although most current historians writing about it conclude that a massacre occurred, however the extent of the massacre in violation of the rules of war compared to casualties suffered in normal combat remains unresolved. The massacre may have been the largest one during the Civil War and certainly was the most famous one.

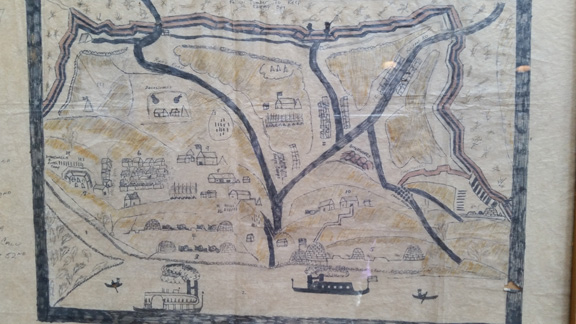

Fort Pillow Folk Map

Image Courtesy of: Fort Pillow State Park Museum

Confederates created Fort Pillow on a high bluff above the Mississippi River about fifty miles north of Memphis, Tennessee. It is best known as one of the war’s most controversial incident, but before that it fell to the Federals and served as a base during their military occupation.

Fort Pillow began on June 6, 1861, with just a battery above the spot where the Mississippi came around Craighead’s Point. Soon Brigadier General Gideon Johnson Pillow, a political general and the post’s namesake, decided to expand it with more artillery and about three and a half miles of earthworks on the land side, as one in a series of fortifications on the river. He pressured planters to volunteer large number of slaves to do the digging, but the fort never had enough troops to effectively man the entire line. When General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, a skilled engineer, took command of the region, he saw the problem and ordered a shorter inner line built closer to the river; this was never finished. Confederates placed two batteries on the riverbank and a number of others in the side and on top of the bluff.

Early garrisons started out in tents and eventually built some cabins. Most were just getting organized, trained, uniformed, and armed. Given that the Confederacy had to do most things from scratch, the quality of materials provided was usually poor. Often troops, slave laborers, engineers, and artillery were transferred to other posts. However, one by one the upper river fortifications fell to the Federals.

After the fall of Island No. 10, Fort Pillow became the front line on the river. A wooden ram fleet and troops converged on the site. On April 13, 1862, a Federal flotilla appeared under the command of Captain Andrew Hull Foote, a very experienced sailor uncomfortable with his experimental ironclads and with being away from the high seas. Foote anchored most of the flotilla out of the fort’s range at Plum Bend and towed some mortar boats down near Craighead Bend to initiate a bombardment to which the Confederates occasionally responded. Major General John Pope led a large army force, most of whom had to stay aboard transports at first due to the river’s flooded condition. Pope sent out scouts to search for a route for an attack by land but could find none on the upriver side. Confederate Brigadier General John Bordenave Villepigue, a very talented professional soldier, readied the fort for combat and kept the Federals under close surveillance.

After a few days Major General Henry Wager Halleck, the regional Federal commander, ordered all of Pope’s force, except one brigade, to Shiloh Landing to join his march against Beauregard at Corinth, Mississippi. The expedition’s reduction in strength caused Foote to feel that Halleck “left us in quite a forlorn condition.” Villepigue learned about Pope’s departure immediately and created a rumor campaign in the neighborhood to convince Foote that the Federals were in grave, imminent danger of an attack. Beauregard gradually transferred many of the Confederates present to the defense of Corinth. [1]

Both sides continued the bombardment. The beginner artillerists in both forces had trouble getting the range right. A Northern reporter observed:

We stand in breathless silence to hear the screaming in the air. We are interested to know where the shot will fall. Every sense is quickened. We live fast for ten or twenty seconds. The shot falls short. We breathe again and laugh at the enemy. [2]

The commander of the mortar boats later reported that their “services have not been near equal to their costs.” Civil War soldiers typically learned to read the sound of a shell and to dodge when necessary. Confederates moved their camps out of range, and consequently only two of Confederates died (both early in the shelling). Federals did not record any such deaths. [3]

Slaves began seeking sanctuary with the Federals, but under Halleck’s strict orders they received it only if bearing military information or escaping from working for the Confederate army. This type of conciliatory policy early in the war tried to win back secessionists by minimizing harm to their property.

Unionists also brought in intelligence and wanted various benefits in return. However, the Federals tended to be suspicious of whites claiming to be supporters.

For most soldiers, life settled into a routine after several schemes for an attack on the fort came to nothing. The Federals did not even have enough dry land to drill until the river fell below flood stage. One infantryman commented that “Each day here is just like the preceding one—all excessively dull—monotonous beyond conception.” They suffered a great deal from mosquitos, which rarely bothered the Confederates on higher ground. [4]

When the navy learned that flooding had damaged the fort’s riverbank batteries, the ship captains debated the wisdom of trying to run past the fort and then ferry infantrymen over at a good crossing point. Worried by the ironclads’ slowness and the damage they suffered from uphill artillery in a battle at Fort Donelson, Foote eventually rejected the idea. An injury, which Foote received at Fort Donelson and had grown worse, led to his departure on a medical leave. Captain Charles Henry Davis, his replacement, arrived on May 8. Davis had experienced little combat and was very influenced by Foote’s worries.

Unfortunately for him, on the morning of May 10 eight Confederate rams launched a surprise attack. In the Battle of Plum Bend, the rams sank two ironclads by punching holes in their unarmored area below the waterline, before being driven off by a heavy Federal cannonade. Both sides had few casualties; early in the war minor battles involving many new soldiers often had a low death rate. Federals refloated and repaired both sunken ironclads. A rattled Davis waited for Halleck to drive Beauregard south from Corinth, because that would leave the fort in an exposed advance position and force its evacuation.

Villepigue successfully masked his withdrawal, which was completed on June 4, 1862. After cautiously confirming that Confederates had retreated, Davis took the flotilla on downriver to Memphis.

Federals stationed one ironclad near the fort, until they installed the 52nd Indiana Infantry under Colonel Edward H. Wolfe as a garrison on September 9. At times some cavalry or other infantry strengthened the fort. These troops, like most of their contemporaries, had switched to a hard war policy by this point. One of the men commented that “The policy of protecting and fighting an enemy at the same time will never win.” Deeming a quick reconciliation impossible, they focused on harshly breaking down resistance by prohibiting trade and appropriating property. Federals set up a refugee camp for runaway slaves, hired some, and eventually enlisted more. [5]

Secessionists judged these actions as violations of traditional rules of war and initiated guerrilla resistance, which Federals considered as breaking the rules. The Confederacy soon tried to recruit the irregulars into partisan ranger regiments. When the experienced Indianans first clashed with a green force of rangers, the Confederates suffered a severe defeat, and little skirmishing occurred thereafter. Captain Franklin Moore of the 2nd Illinois Cavalry effectively collected intelligence and kept up constant pressure on the ranger recruiters’ camps with lightning raids. More successful than most anti-guerrilla forces, Moore’s men eventually succeeded in driving most rangers out of the area. But, when the army reassigned him, partisan activity, sometimes combined with banditry, revived. Civilians were forced to stay mostly at home. In November, 1863, Confederate Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest raided through the area and absorbed as many guerrillas as possible into his command. On January 21, 1864 the fort closed under orders from Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, who considered it no longer needed.

However, on February 8, the fort reopened. Major General Stephen Augustus Hurlbut, a subordinate commander, wanting to protect unionists and revive trade, ignored Sherman’s orders. He gradually built up the garrison to around 600 men, about half whites and half blacks. They came from Bradford’s Tennessee Cavalry Battalion, the 6th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery, and the 2nd U.S. Colored Light Artillery, all units under formation. The fort’s commander, Major Lionel F. Booth, rebuilt an earthwork from Beauregard’s inner line near his camps on the river bluff. He armed it with six pieces of field artillery. A wooden gunboat, the New Era, added to the post’s defenses.

In mid-March Forrest launched a raid through Western Tennessee and Kentucky. On April 10 and 11 he sent some 1500 of his men on a rapid march from Eaton and Jackson, Tennessee, for an attack on Fort Pillow. At dawn on April 12 after a rainy night, Brigadier General James Ronald Chalmers, commanding the head of the column, surprised the Federal pickets at the outer line gates. An alerted Booth sent forward a skirmish line. The more numerous and experienced Confederates, despite shelling from the New Era, slowly drove the skirmishers back to rifle pits outside the rebuilt fortification from which the rest of the garrison opened fire. Eight armed civilians, possibly local militiamen, aided the Federals. The New Era towed a number of noncombatants, including runaway slaves, upriver in a barge before returning to combat. Colonel Clark Russell Barteau’s snipers harassed these vessels from a position at the junction of Cold Creek and the Mississippi a little north of the inner fort. Advancing Confederates drove off some Federals attempting to burn cabins too close to the fortification. When a sniper killed Booth, the post’s command passed to Major William F. Bradford, leader of the Tennessee Cavalry Battalion.

Chalmers’ troops were forming a crescent around the inner fort, when Forrest arrived. After reconnoitering the fort and getting badly bruised when his horse was shot, Forrest completed the process by posting marksmen on the highest points and by sending a force to take control of the cabins. The latter movement enabled Confederates to close down the two closest cannon ports and forced the Federals in the rifle pits to retreat inside the inner fortification. Confederate troops moved out of sight into the steep ravines around it. Forrest also placed some of his artillery on a hill to fire on the New Era.

About 2:00 p.m., having poised himself for a victory, the Confederate general called a truce. He wanted a Federal surrender and offered to accept the entire enemy force as prisoners, a comparatively generous stand as the Confederacy officially would have black troops either returned to owners or executed as rebellious slaves. He did add that “Should my demand be refused, I cannot be responsible for the fate of your command,” a vaguer threat than the explicit one of no quarter he had used elsewhere. During the truce jeering broke out between the two forces. One Confederate recorded the Federals as “threatening that if we charged their breastwork to show no quarter.” Such words from African American and white Southern unionists riled the Confederates. The Federals felt secure in the fort, and both sides could see smoke from steamboats coming upriver. If Forrest had not done so already, he now sent Major Charles W. Anderson with a detachment to the riverbank below the fort, and the men opened fire on the commercial vessels, all of which turned back, except one. That steamer carried some artillerymen, but a general on board believed they could do no good from the riverbank and ordered the captain to head upriver for help. Meanwhile a crew of Confederates snuck into the fort’s trench beneath a cannon they intended to disable. After dragging the truce out, Bradford refused to surrender. [6]

At 3:15 p.m. the Confederates charged from positions much closer than Federals expected. Confederate sharpshooters limited the effectiveness of Federal fire into the charge, and the group in the trench killed the cannon’s crew. When the Confederate tide crested the earthwork, it routed the Federals and sent them fleeing down the bluff. Upon reaching the riverbank, Federals found themselves trapped by Barteau’s and Anderson’s men on either side. They tried to surrender, but a massacre began.

None of the Confederates in the battle had previously fought in close combat with black Federals, something new and disturbing to them. One reported later that “the sight of negro soldiers stirred the bosoms of our soldiers with courageous madness.” [7] Similar massacres of black Federals occurred during the war, especially at the Battle of Poison Spring, Arkansas, and the Petersburg Crater, Virginia. Exhaustion from the hard march and exasperation with Federal taunting may have further undermined self-control. While there is little contemporary evidence of depredations by Bradford’s Battalion, a new unit still under formation, Confederates generally held a negative image of unionists for harming rebel families and for betraying the homeland. This may have further antagonized some of Forrest’s men. Confederate Sergeant Achilles V. Clark described the incident:

The slaughter was awful. Words cannot describe the scene. The poor deluded negroes would run up to our men fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands would scream for mercy but they were ordered to their feet and shot down. The white [sic] men fared but little better. Their fort turned out to be a great slaughter pen. Blood, human blood stood about in pools and brains could have been gathered up in any quantity. [8]

The practice of Forrest’s veterans to carry two revolvers besides their rifle facilitated rapid killing. Some Federals kept trying to surrender, while others tried to escape by flight or grabbed weapons to go down fighting.

Sergeant Clark and some other Confederate officers tried unsuccessfully to stop the massacre. Clark believed that he failed because “Forrest ordered them shot down like dogs,” but neither he nor anyone else ever claimed to witness the general issue such an order. Some Confederates were shouting that there was such an order perhaps just to justify their actions, and the young sergeant believed them. If Forrest made such an order in impulsive anger after the charge, he soon changed his mind. After the charge he rode into the little fort, eventually ordered the massacre stopped, and even shot one soldier who ignored him. Several black artillerymen, like Samuel Green, would state that “If it had not been for General Forrest coming up and ordering the Confederates to stop killing the prisoners, there would not one of us been alive today.” [9]

Confederate casualties were low. The Federals, however, lost from 47 to 48% (277-295) of the garrison dying that day or later from wounds. It is impossible to separate those killed in the battle from those massacred, although the post surgeon reported only about thirty casualties before the Confederate charge. The death rate varied by race: 65% for blacks and 29-33% for whites. One Confederate reported that “The whites received quarter, but the negroes were shown no mercy.” [10]

Several consequences followed the incident. Because cavalry raiders behind enemy lines needed to move fast, Forrest paroled wounded captives the next day. They immediately reported the massacre, and a number of accounts soon appeared in Northern newspapers. A few Southern papers ran a Confederate’s massacre account or a gloating editorial, but, as soon as they learned of Federal condemnation, adopted a position of denial. The debate over what happened has continued ever since then, although most current historians writing about it conclude that a massacre occurred. After the incident General Sherman ordered that the fort be left abandoned. In subsequent battles black troops fought fiercely hoping to avoid a repeat of the massacre, and some even conducted little massacres of revenge. Confederate officials generally sent captured black soldiers to prison camps and included them in prisoner exchanges when those reopened in 1865. The United States Congress quickly equalized the black troops’ privileges in most ways, so that both sides in practice started to treat them as legitimate soldiers. The massacre may have been the largest one during the Civil War and certainly was the most famous one. While Fort Pillow was an active post during most of the war, it is unquestionably best known for the April 12, 1864 incident.

- [1] United States Navy Department, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 31 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894-1927), Series I, volume 23, p. 8 (hereafter cited as O.R.N., I, 23, 8).

- [2] Boston Journal, April 25, 1862.

- [3] O.R.N., I, 23, 280.

- [4] Democratic Pharos (Logansport, IN), May 21, 1862.

- [5] Decatur Republican (Greensburg, IN), January 15, 1863.

- [6] United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 32, part 1, p. 614; John Cimprich and Robert C. Mainfort, Jr., eds., “Fort Pillow Revisited: New Evidence about an Old Controversy,” Civil War History 28 (December, 1982): 299.

- [7] Ibid., 301.

- [8] Ibid., 299.

- [9] Ibid.; Deposition, March 30, 1887, Samuel Green Pension File (11th U.S.C.I.—New), RG 15, National Archives.

- [10] Cimprich and Mainfort, eds., “Fort Pillow”, 304.

If you can read only one book:

Cimprich, John V. Fort Pillow, a Civil War Massacre, and Public Memory. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Books:

Glatthaar, Joseph T. Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers. New York: Free Press (Macmillan), 1990.

Hughes, Jr., Nathaniel C. Brigadier General Tyree H. Bell, C.S.A.: Forrest’s Fighting Lieutenant. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2004, 81-126.

Hughes, Jr., Nathaniel C. and Roy P. Stonesifer, Jr. The Life and Wars of Gideon J. Pillow. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993, chap. 1-10.

Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War: Fort Pillow Massacre, H.R. Rep. No. 38-65 (1864).

Slagle, Jay. Ironclad Captain: Seth Ledyard Phelps and the U.S. Navy, 1841-1864. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1996, chap. 9.

Thomas Jordan & J.P. Pryor. The Campaigns of Lieut. Gen. N.B. Forrest, and of Forrest’s Cavalry. New Orleans: Blelock, 1868, 416-55.

Tucker, Spencer C. Andrew Foote: Civil War Admiral on Western Waters. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000, chap. 9-12.

Wills, Brian Steel. The River Was Dyed with Blood: Nathan Bedford Forest and Fort Pillow Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014, chap. 4-8.

Wyeth, John A. The Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1899, chap. 14.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

Fort Pillow State Historic Park

The Fort Pillow State Historic Park preserves the site of the Fort. The park’s museum offers Civil War artifacts including a canon and interpretive displays relating to the history of Fort Pillow. The park is open from 8:00 a.m. until sunset and the Museum is open from 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. seven days a week. Both are closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day. The park’s address is 3122 Park Road, Henning TN 38041, 731 738 5581.