Occupation: Federal Military Government in the South

by Jacqueline G. Campbell

Approximately one hundred southern towns and cities were occupied by Union forces at one time or another during the course of the Civil War. Northern policy initially encouraged southern Unionism which Lincoln and others believed to prevail among the majority of the southern population. They also believed (erroneously) that reinstalling loyal people and reintegrating the state into the Union would be a relatively simple process. But the complexities of occupational politics were myriad and the United States had only minimal experience as occupiers during the Mexican American war. Unlike their presence in a foreign country however, occupying forces in the American Civil War shared a legacy with the South; nor was it clear whether the seceding states were belligerent enemies or misguided family members who only required to be persuaded of their errors. As larger areas of the South came under Union control the Union faced enormous administrative challenges and questions arose as to how to reignite loyalty to the Union, how to deal with fugitive slaves, and how to deal with the vigilante violence that sprang up around occupied areas. All of these problems had to be worked out during the course of the war.

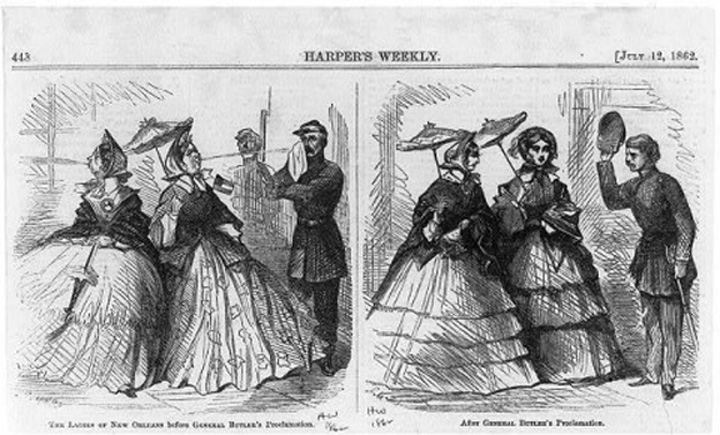

The Effect of General Butler's Order No. 28 on the Women of New Orleans

Illustration From: Harper's Weekly July 12, 1862, 448.

Approximately one hundred southern towns and cities were occupied by Union forces at one time or another during the course of the Civil War.[1] Northern policy initially encouraged southern Unionism which Lincoln and others believed to prevail among the majority of the southern population. They also believed (erroneously) that reinstalling loyal people and reintegrating the state into the Union would be a relatively simple process. But occupation turned out to be far more complex and the United States had only minimal experience as occupiers during the Mexican American war. Unlike their presence in a foreign country however, occupying forces in the American Civil War shared a legacy with the South; and it was not clear whether the seceding states were belligerent enemies or misguided family members who only required to be persuaded of their errors. As larger areas of the South came under Union control the Union faced enormous administrative challenges. Questions arose as to how to reignite loyalty to the Union, how to deal with fugitive slaves, and how to deal with the vigilante violence that sprang up around occupied areas. All of these problems had to be worked out during the course of the war. Because of its complexities few scholars until recently have focused directly on occupation but many have written around the topic.[2]

The first serious examination of occupation during the American Civil War began in response to the experiences of the United States during World War II and sought explanations and roots of occupational policies. In his 1951 essay Robert Futrell claimed that the topic of Federal military government in the South was “virgin territory” in the history of the American Civil War and that given the “worldwide governmental activities of American leaders” an examination of the development of the field of military government was now pertinent. Other articles had in fact appeared in the 1940’s which had traced the origins of occupational politics as set out by General Winfield Scott during the Mexican American War in his General Orders No. 20 leading up to General Orders No. 100, of 1863 which provided a comprehensive framework of how to deal with questions of martial law and the treatment of noncombatants and private property. Most of these early scholars were seeking the roots of a distinctive true American occupation policy and they agreed that, despite a standard interpretation of the laws of war, the methods employed were very much dependent on individual commanders and the specific geographical context.

Although Futrell was not the first to examine the topic, he did provide an early comprehensive study. While he agreed with others that much discretion lay in the hands of individual commanders, he concludes that most pursued remarkably similar policies. Mostly they used their martial powers to control recalcitrant populations. Nevertheless, military commanders did not seek to reform the Southern social system. While Futrell made extensive use of letter books, military records, and other ground-level primary sources his interpretation very much reflected the view of his generation that it was politicians who had pursued a policy of continued military occupation during Reconstruction.[3]

The following two decades saw an increasing number of case studies that examined specific occupations in Arkansas, Virginia and Florida. These more focused examinations looked at the challenges of encouraging loyalty over extremely recalcitrant populations. Many of these anticipated later explorations of guerrilla warfare and of the development of both official policies regarding civilian-military relations and the ground level experience of ordinary soldiers interacting with local populations. One of the first scholars to look at the view from the bottom up was Bell Wiley who examined Southerners’ reactions to Federal invasion. A pioneer in the study of the common soldier, Wiley turned his focus on civilians and, in particular, the attitudes of Southern women to enemy soldiers. Wiley argued the early animosity displayed by many decreased over time as personal interactions increased. This, he argues, was largely shaped by the good behavior of Yankee soldiers and by pragmatism among civilians who needed to survive with some sense of normality.[4]

Gerald Capers’ study of New Orleans provided the first in depth examination of an occupied city. The largest city in the Confederacy fell to Union forces in April 1862 and remained under Union control for the entire war. Capers goal was to examine “the problems of the conqueror and the response of an urban population to military occupation.” Among these problems were the unemployment and food shortages that existed even before the city fell. Capers argues that New Orleans actually suffered very little under occupation and that the economy of the city actually benefited from Federal rule. The goal of the Union was to make New Orleans a base for further conquest, to encourage Unionism, and to return Louisiana as a loyal state, thus establishing a model for future reconstruction plans. As in other places this proved challenging as long as the city hoped for deliverance by the Confederate forces. Benjamin Butler, the first military commander, was determined to rule with an iron fist, earning him the nickname of “Beast.” When Butler was replaced by the far more conciliatory Nathaniel Banks, Louisiana saw this as a sign of weakness. Despite the fact that a new constitution was adopted in 1864 that accepted emancipation, the city retained a Confederate heart and thus Lincoln’s early restoration model proved a failure.[5]

The opportunities that occupation offered for experimentation was a factor in Willie Lee Rose’s study of the transition from slavery to freedom in the South Carolina Sea Islands. Rose claimed that what had begun as a move to establish a base for a naval blockade became what he termed a Rehearsal for Reconstruction. In late 1861 when the Union Navy captured the region, many planters fled leaving behind large cotton crops and thousands of slaves whose status was unclear. Rose examined the complex interrelationships between government agents, soldiers, missionary volunteers and newly freed people. This early experiment in occupation policy and plans for reconstruction highlighted problems rather than provided solutions. It soon became clear that while missionaries were eager to provide education to ex-slaves, economic interests dictated that cotton production be resumed. Rather than provide solutions, this particular experiment highlighted the problems of competing interests.[6]

Two of the most compelling of these competing interests were the thirst for profits versus military necessity. Nowhere was this more evident than in the problems that surrounded trade. The question of “Blockade or Trade Monopoly” was thoroughly explored by Ludwell Johnson in his study of “John Dix and the Occupation of Norfolk Virginia.” This was a more expanded and focused version of a study Johnson had completed fifteen years earlier tracing early Confederate policy towards the question of trade with the North. Johnson argued that the term “military necessity” proved to be very elastic as it encompassed not only the war effort, but the new demands on occupation forces to provide for civilians under their jurisdiction. As the Union occupied much of the rich agricultural land, destroyed railroads, and tightened blockades, they jeopardized Southern supplies, both domestic and foreign. Yet at the same time Southerners gained easier access to Northern markets. While logic dictated that cotton should be exchanged for much needed food this was a difficult decision. Such a move might demoralize the Southern people and there was a growing danger that more and more Southerners were becoming dependent on the North for vital supplies. Thus in April 1862 the Confederate Congress had forbidden the transportation of any goods to areas under Union occupation. Despite this, trade continued after the fall of Memphis and New Orleans. By 1863 Confederate President Davis acknowledged that shortages of provision might present one of the greatest dangers to the war effort. His efforts to encourage Southerners to raise less cotton and more food was somewhat unrealistic as the Union controlled much of the productive areas of the South and were making distribution of provisions increasingly difficult. Looking at the situation from the Union perspective in occupied Norfolk, Johnson examined the possibility that occupation might actually facilitate supplies reaching the enemy. He also highlighted the larger ramifications in international policy. Lincoln had issued a proclamation stating that neutral countries (specifically Britain and France) were not permitted to trade with states in rebellion. But once occupied was a state still in rebellion? And could the Union maintain a blockade once it occupied those ports? By examining these questions Johnson highlighted the connections between occupational policy and international diplomacy.[7]

One of the first scholars to recognize that occupation encompasses a variety of themes was Peter Maslowski in his study of military occupation and wartime reconstruction in Nashville. Maslowski examined the evolution of civil military relations, policies for reconstruction, as well as the slavery question. Nashville, the first Confederate capital to fall, was occupied in February 1862 and within two weeks Lincoln appointed Andrew Johnson as military governor with the charge of reestablishing Tennessee’s loyalty. By August Johnson had determined that “Treason Must be made Odious” as Maslowski entitled his study. Johnson called for harsher measure against Confederate sympathizers and although he did succeed in establishing a functioning civil government large numbers still remained loyal to the Confederacy clinging to the hope that Confederate forces would liberate them from Yankee rule.[8]

Walter Durham, the state historian of Tennessee during the 1980s followed Maslowski on this path of early social histories with two books on the occupation of Nashville. Durham examined the multiple ways that occupational politics affected the lives of the people and concurred with Maslowski’s finding that most never shifted their loyalties. Despite the best efforts of the army and military governors, Nashville remained a Confederate city. For the most part both authors agreed that it was inexperience with occupation that made for the inconsistent policies exercised by military government.[9]

Reflecting the post-Vietnam interest in guerilla warfare, Michael Fellman moved away from traditional military history into a study of irregular warfare. His study of war torn Missouri examined the predicament of civilians and proved especially insightful on the experiences of women. When Union regiment secured the state, they forced Confederate sympathizers to flee or go underground. This action, in turn, initiated an irregular warfare designed to free communities from occupying troops. By mid-1862 Missouri was bloodier than any battlefield. As the lines between civilians and combatants became increasingly blurred, Union soldiers came to see all southerners as the enemy and partisan warfare produced horrendous acts of violence that neither side was prepared to handle. Policies varied from mild to brutal, from executions of suspected guerrillas to wholesale evacuations of civilian population. Fellman reveals that because these boundaries became so blurred, it was the ordinary soldiers that more often determined policy than their commanders, while civilians became trapped in a cycle of blood and terror. Ultimately, according to Fellman, this type of guerrilla warfare that occurred not only in Missouri but also in Arkansas and Kansas had less impact on the military situation than in civilian suffering. Fellman’s study represents yet another methodological turn as he incorporated psycho-history and concluded that, for Missourians, the war was less about secession or slavery and more about cultural survival.[10]

The occupation that Wayne Durrill studied the following year was indeed “war of another kind.” This micro-history of a north-eastern North Carolina county focused on an inner war of economic interest. Union troops occupied the county in August 1861 and by the following summer their presence had transformed the political landscape. The previous planter-yeoman alliance collapsed while landless whites and some slaves seized the opportunity to restructure their world. Landless white laborers allied themselves with disenchanted yeoman farmers; slaves who had been moved upcountry tried to renegotiate their relationships with displaced masters. Although Confederate forces regained control for a short period in 1864, it was too late for planters to reassert their authority. According to Durrill this was more than a conflict for independence, it was also a power struggle for who would wield political power the wake of war. Durrill’s focus on an inner socio-economic war reflected an interest in the changes that occupation brought to the ante-bellum social structure.[11]

Another book length study of a community under occupation appeared in 1995 when Daniel Sutherland examined Culpepper County, Virginia. This was a highly strategic area on the sole railroad that connected North and South in the east and the nearest station to Richmond. Both armies contested control over the area which led to increased tensions in the community. And, this being one of the first occupied regions in the Confederacy, the Union Army experimented in its treatment of civilians, many times in a harsh manner. In fact, as Sutherland’s title makes clear, his evaluation of the experience was an “ordeal” for this community. According to Sutherland, Culpepper County remained committed to the Confederacy and there is little indication of the inner divisions that Durrill found in North Carolina. The agony of the Culpepper community drew the white community together in a downward spiral of despair.[12]

Sutherland’s study is less an analytical than a narrative approach designed to tap into the emotional experiences of both civilians and the military communities. In contrast to this vivid and evocative exploration of the pain and suffering of civilians, that same year brought two complementary studies that brought a more analytical eye to the same subject. Mark Grimsley’s study of the evolution of Union policy towards civilians is not specifically about occupation, but, because occupation brought civilians and the military into day to day contact it adds a vital dimension to the topic. Grimsley rejected the term “total war” arguing instead that Union policy towards Southern civilians evolved from one of conciliation to “hard war” but never escalated into violence against civilians.[13]

An initial policy of conciliation sought to limit civilians’ exposure to wartime hardships, but especially in the western theater, this policy lost its allure and a more pragmatic policy emerged. Grimsley argues that this move was largely forged by ordinary soldiers’ attitudes as they came into increasing contact with civilians in areas of occupation and where guerrilla warfare raged. This bloody violence led to increasing blame being placed on the shoulders of civilians which, in turn, challenged conventional war tactics. Nevertheless, the army still exercised restraint and controlled their severity, reflecting the fact that Union soldiers were not “brutes” but often “men from good families, with strong moral values that stayed their hands as often as they impelled retribution.” Although Grimsley’s work is largely a top down study of military policy, he does illuminate the influence of the attitudes of lower ranking officers and ordinary soldiers and provides an enlightening journey through the twists and turns of evolving union policy.[14]

While Grimsley provides a predominantly Northern perspective, Stephen Ash examines the way in which Southern civilians experienced those evolving policies. In the first comprehensive study of the occupied South, Ash concurs with Grimsley that the Yankees never waged a “total” war against civilians and always maintained a distinction between combatants and non-combatants. Nevertheless, he makes us acutely aware of the perceptions of those white civilians who saw the presence of Yankees in terms of “violation, pollution, and degradation.” Ash argues that occupation had not only a “temporal dimension” as explored by Grimsley in the transformation of policy over time, but also “a spatial dimension.” He identified three distinctive areas: the “garrisoned town” where citizens lived in the constant presence of the enemy; the “confederate frontier,” where only sporadic encounters took place and finally “no man’s land,” a liminal space surrounding the garrisoned towns where the worst episodes of guerrilla warfare were most likely to occur. The arrival of Federal forces engendered conflict between rebels and Unionists, particularly outside the garrisoned towns which provided the safest haven for Unionists. But even in the relative safety of garrisoned towns, Southerners often became dependent on Yankees for provisions which increased class tensions. Occupation not only shaped Union policies it also created unrest within Southern society, and as Ash’s evocation of “conflict and chaos” in his subtitle suggests, this was a painful process with severe disruptions and dislocations. Although Ash found some uneasy alliances within Southern society, he argues that in the end elites were never truly toppled. These conclusions do contrast with Durrill’s argument for North Carolina, however, Ash gives us an overview of the occupied Confederacy whereas Durrill’s book is a micro-history of the experience of one particular county.[15]

In East Tennessee, a particularly volatile and geographically isolated area, Noel Fisher found a continuously divided populace. Occupation proved a brutal experience for many civilians and a frustrating one for soldiers whose exposure to irregular warfare and enduring resistance only increased their tendency to throw restraints by the wayside and employ more draconian measures. These geographically specific studies not only point to the challenges in dealing with occupation in an all-encompassing manner but also leaves open the question as to whether we need more community studies to further modify or confirm that larger picture of military strategy.[16]

The early years of the twenty-first century have brought more case studies on St. Louis, Winchester, Natchez, Winchester, and Alexandria and also the first textbook to include a chapter on Occupation. But 2009-11 proved to be bumper years producing three books that tackle the topic in new and innovative ways. Daniel Sutherland’s study of guerrilla war is a reflection of contemporary interest in events in Iraq and Afghanistan that has raised new questions about occupation and guerilla warfare. Sutherland examines the ways in which this “savage conflict” disrupted civilian life and affected military policy. He identifies three separate groups: guerrillas operating independently of armies; partisan rangers who were officially sanctioned by the Confederate government; and bushwhackers, who were predominantly deserters or outlaws. Although many shared attack strategies Sutherland found that different cultures across the home front spawned regionally specific methods. Most importantly Sutherland finds that this irregular warfare fundamentally shaped military policy in its struggle to come up with an adequate response. Although standard codes of war were in place, local experiences challenged their viability. Sutherland also suggests that guerrilla warfare might actually have weakened the Confederacy by exposing civilians to such levels of violence that they lost their trust in the ability of their government to protect them. As the war continued, many of these guerrilla warriors became more concerned with personal gain than Confederate independence and ultimately may have been more of a burden than an advantage to the Southern war effort. Sutherland also argues that the Union counter-response was an even more vigorous occupation and was part of what hastened the war’s end.[17]

As his title suggests, Judkin Browning found “shifting loyalties” in occupied eastern North Carolina among both civilians and soldiers. Browning wishes to fill a vacuum in the story by examining the change in attitudes of ordinary soldiers who served as the occupying forces. Moving beyond Grimsley, Browning examined the ways in which these soldiers interpreted their own roles. Ultimately Browning argues that Union soldiers became increasingly cynical as a result of their frustration at the lack of action and the enduring hostility of Southern civilians. Although they had initially congratulated themselves on being liberators after prolonged periods of being despised by the local population and denied the glory of active combatant they often found themselves cast in the role of oppressors. From the civilian perspective Browning found the nature of Southern Unionism to be an ambiguous one largely shaped by pragmatism rather than patriotism. In fact, the policy of cultivating Unionism frequently backfired and many inhabitants who had been only conditional Confederates became even more dedicated to the Southern cause as a direct result of the occupation which lasted from March 1862 until the end of the war. Browning gives a new dynamism to the concept of loyalty in his examination of the ways in which occupational politics affected all the players.[18]

LeeAnn Whites and Alecia Long’s collection of essays on “Occupied Women” is deigned to illuminate the merger of home front and battle front that created “a new kind of battlefield” where civilians, many of whom were women actively resisted what they saw as “illegitimate domination.” In the introduction Whites and Long argue that most studies of military occupation have focused on Union military policy and that even those who focus on the home front have limited their views to conflict between men. Their view is that occupation “both activated and was often fought as a gender war” The failure to examine the critical role of gender has, they argue created a blind spot that obscures the vital roles of the female population. Their efforts seek to redress this by examining the role of female activism in shaping military policy as well as the race, class and cultural difference among these women that exposes “occupations within occupation.” Their purpose is to use the term “occupied” in the active, not just the passive sense. Although frequently victims of occupation, the interaction of women with the enemy made their roles critical, and thus it takes our understanding of occupation to a place where it is driven by the occupied. While this volume certainly succeeds in focusing on female actions in occupied territories it does not consider the “gendered” roles of occupied men which would be a further step in approaching the study of occupation.[19]

Clearly there is a growing subfield of occupational studies and it is one that helps us move beyond the artificial division of home front and battlefront into an area that encompasses a variety of topics. New monographs are currently under way that range from a focused study of the early occupation of New Orleans, to a more comprehensive examination of the cultural meaning of occupation itself. Jacqueline Glass Campbell’s forthcoming examination of the occupation of New Orleans under Benjamin Butler goes beyond an examination of the controversies surrounding his administration. Setting Butler’s administration in its larger social, political, military, and international context this work promises to reveal their complex interconnections. Andrew Lang’s project makes three broad arguments. First, that occupational practices collided with a long-standing culture of citizen-soldiering; second, that race emerged as a central determinant of wartime occupation and, finally, that white Union soldiers’ aversion to wartime military occupation ultimately predicted the national retreat from Reconstruction.[20]

This is a burgeoning new field and one that touches on myriad themes including the evolution of military policy, wartime diplomacy, economics, and strategies for reconstruction. As such it offers historians an opportunity to write a much more integrative history of the American civil war.

- [1] Aaron Sheehan-Dean, ed., A Companion to the U.S. Civil War, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 328-337.

- [2] Paul Foos, A Strange, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict During the Mexican-American War. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Irving Levinson, Wars within Wars: Mexican Guerrillas, Domestic Elites, and the United States of America, 1846-1848. (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 2005).

- [3] Robert J. Futrell, “Federal Military Government in the South, 1861=1865,” Military Affairs, Vol. 15, No. 4 (Winter, 1951): 181, 191; see also Ralph H. Gabriel, “American Experience with Military Government,” American Historical Review, Vol. 49, No. 4 (July, 1944): 630-43; Administrative Activities of the Union Amy During and After the Civil War,” Mississippi Law Journal, Vol. 17, (May, 1945): 71-89; Frank Freidel, “General Orders 100 and Military Government,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Mar, 1946): 541-56.

- [4] Omega G. East and H. B. Jenckes, “St. Augustine during the Civil War,” Florida Historical Quarterly Vol. 21, No. 2 (Oct., 1952): 75-91; Ruth Caroline Cowen, “Reorganization of Federal Arkansas, 1862-1865,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly Vol. 18, No. 2 (Summer, 1959): 32-57; Susie M. Ames, “Federal Policy toward the Eastern shore of Virginia in 1861,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 69, No. 4 (Oct., 1961): 432-59; James I. Robertson Jr., “Danville under Military Occupation, 1865” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Vo. 75, No. 3 (July, 1967): 331-48; Nola A. James “The Civil War Years in Independence County,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly Vol. 28, No. 3 (Autumn, 1969): 234-74; Bell I. Wiley, “Southern Reaction to Federal Invasion,” Journal of Southern History, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Nov., 1950): 491-510.

- [5] Gerald J. Capers, Jr., Occupied City: New Orleans under the Federals 1962-1865 (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1964), vii; For the most recent work on Butler in New Orleans see Jacqueline Glass Campbell, “The Unmeaning Twaddle about Order 28: Benjamin F. Butler and Confederate Women in Occupied New Orleans, 1862” The Journal of the Civil War Era, Vol. 2, No. 1 (March 2012): 11-30; and “A Unique but Dangerous Entanglement”: Benjamin Butler in New Orleans, April-December, 1862 (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming).

- [6] Willie Lee Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill,1964).

- [7] Ludwell H. Johnson, III, “Trading with the Union: The Evolution of Confederate Policy.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 78, No. 3 (July 1970): 308-25; and his “Blockade or Trade Monopoly? John A. Dix and the Union Occupation of Norfolk,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 93, No. 1 (Jan., 1985): 54-78.

- [8] Peter Maslowski, “Treason Must be Made Odious”: Military Occupation and Wartime Reconstruction in Nashville, Tennessee, 1862-1865 (Millwood, N.Y.: KTO Press, 1978).

- [9] Walter R. Durham, Nashville, The Occupied City, The First Seventeen Months – February 15, 1862 to June 30, 1863 (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society, 1985); and his Reluctant Partners: Nashville and the Union, July 1, 1863 to June 30 1865 (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society, 1987).

- [10] Michael Fellman, Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the American Civil War. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989).

- [11] Wayne K. Durrill, War of Another Kind: A Southern Community in the Great Rebellion. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

- [12] Daniel E. Sutherland, Seasons of War: The Ordeal of a Confederate Community, 1861-1865. (New York: The Free Press, 1995).

- [13] Mark Grimsley, The Hard Hand of War: Union Policy Toward Southern Civilians 1861-1865. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- [14] Ibid., 190-91, 204.

- [15] Stephen V. Ash, When the Yankees Came: Conflict & Chaos in the Occupied South 1861-1865 (ChapelHill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 40, 76-77.

- [16] Noel Fisher, War at Every Door: Partisan Politics and Guerrilla Violence in East Tennessee, 1860-1869. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997).

- [17] Louis S. Gerteis, Civil War St. Louis. (Lawrence: University Press, of Kansas, 2001); Richard R. Duncan, Embattled Winchester: A Virginia Community at War, 1861-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007); Joyce L. Broussard, “Occupied Natchez, Elite Women, and the Feminization of the Civil War” Journal of Mississippi History Vo. 70, No. 2 (Summer, 2008): 179-207; Diane Riker, “This Long Agony”: A Test of civilian Loyalties in an Occupied City” The Alexandria Chronicle, No. 2 (Spring, 2011): 1-10.; Scott Nelson and Carol Sheriff, A People at War: Civilians and Soldiers in America’s Civil War, 1854-1877 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 85-98; Daniel E. Sutherland, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

- [18] Judkin Browning, Shifting Loyalties: The Union Occupation of Eastern North Carolina (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2011) .

- [19] LeeAnn Whites and Alecia P. Long, eds., Occupied Women: Gender, Military Occupation, and the American Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), 3-10.

- [20] Jacqueline Glass Campbell “A Unique but Dangerous Entanglement”: Benjamin Butler in New Orleans, April-December, 1862 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming); Andrew F. Lang, Waging Peace in the Wake of War: United States Soldiers, Military Occupation, and the American Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, forthcoming, Fall 2017).

If you can read only one book:

Ash, Stephen V. in the Occupied South 1861-1865. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Books:

Ames, Susie M. “Federal Policy toward the Eastern shore of Virginia in 1861,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 69, no. 4 (Oct., 1961): 432-59.

Broussard Joyce L. “Occupied Natchez, Elite Women, and the Feminization of the Civil War” Journal of Mississippi History Vo. 70, no. 2 (Summer, 2008): 179-207.

Browning, Judkin. Shifting Loyalties: The Union Occupation of Eastern North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Campbell, Jacqueline Glass. “A Unique but Dangerous Entanglement”: Benjamin Butler in New Orleans, April-December, 1862. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming.

Capers, Gerald J. Jr. Occupied City: New Orleans under the Federals 1862-1865. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1965.

Cowen, Ruth Caroline. “Reorganization of Federal Arkansas, 1862-1865,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly Vol. 18, no. 2 (Summer, 1959): 32-57.

Duncan, Richard R. Embattled Winchester: A Virginia Community at War, 1861-1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007.

Durham, Walter R. Nashville, The Occupied City, The First Seventeen Months – February 15, 1862 to June 30, 1863. Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society, 1985.

———. Reluctant Partners: Nashville and the Union, July 1, 1863 to June 30 1865. Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society, 1987.

Durrill, Wayne K. War of Another Kind: A Southern Community in the Great Rebellion. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

East, Omega G. and H. B. Jenckes. “St. Augustine during the Civil War,” Florida Historical Quarterly Vol. 21, no. 2 (Oct., 1952): 75-91.

Fellman, Michael. Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the American Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Fisher, Noel. War at Every Door: Partisan Politics and Guerrilla Violence in East Tennessee, 1860-1869. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Foos, Paul. A Strong, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict During the Mexican-American War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Freidel, Frank. “General Orders 100 and Military Government,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 32, no. 4 (Mar., 1946): 541-56.

Futrell, Robert J. “Federal Military Government in the South, 1861-1865,” Military Affairs, Vol. 15, no. 4 (Winter, 1951): 181-191.

Gabriel, Ralph H. “American Experience with Military Government,” American Historical Review, Vol. 49, no. 4 (Jul., 1944): 630-43.

Gerteis, Louis S. Civil War St. Louis. (Lawrence: University Press, of Kansas, 2001).

Grimsley, Mark. The Hard Hand of War: Union Policy Toward Southern Civilians 1861-1865. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

James, Nola A. “The Civil War Years in Independence County,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly Vol. 28, no. 3 (Autumn, 1969): 234-74.

Johnson, III, Ludwell, H. “Trading with the Union: The Evolution of Confederate Policy.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 78, No. 3 (July 1970): 308-25.

———. “Blockade or Trade Monopoly? John A. Dix and the Union Occupation of Norfolk,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 93, no. 1 (January 1985): 54-78.

Lang, Andrew F. In the Wake of War: Military Occupation, Emancipation, and Civil War America. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017.

Levinson, Irving. Wars within Wars: Mexican Guerrillas, Domestic Elites, and the United States of America, 1846-1848. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 2005).

Maslowski, Peter. “Treason Must be Made Odious”: Military Occupation and Wartime Reconstruction in Nashville, Tennessee, 1862-1865 (Millwood, NY: KTO Press, 1978.

Nelson, Scott and Carol Sheriff. A People at War: Civilians and Soldiers in America’s Civil War, 1854-1877. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Riker, Diane. “This Long Agony”: A Test of civilian Loyalties in an Occupied City” The Alexandria Chronicle, no. 2 (Spring, 2011):1-10.

Robertson, Jr., James I. “Danville under Military Occupation, 1865” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Vo. 75, no. 3 (July, 1967): 331-48.

Rose, Willie Lee. Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1964.

Russ, Jr., William A. “Administrative Activities of the Union Army During and After the Civil War,” Mississippi Law Journal Vol. 17, (May, 1945), 71-89.

Sutherland, Daniel E. Seasons of War: The Ordeal of a Confederate Community, 1861-1865. New York: The Free Press, 1995.

———. A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Whites, LeeAnn and Alecia P. Long, eds. Occupied Women: Gender, Military Occupation, and the American Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009.

Wiley, Bell I. “Southern Reaction to Federal Invasion,” Journal of Southern History, Vol. 16, no. 4 (Nov., 1950): 491-510.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.