Partisans and Guerrillas

by Daniel E. Sutherland

The Role of Partisans and Guerrillas in the Civil War

Most Americans in 1861, certainly most political and military leaders, expected the Civil War to be fought along familiar lines. Large massed armies, it was assumed, would confront and maneuver against one another in the open field. The best commanded, most inspired armies would then win the day. The reality of war was quite different, and no more so than in the widespread guerrilla conflict that became an integral part of the wider contest. In point of fact, it is impossible to understand the Civil War without appreciating the scope and impact of the guerrilla conflict. As much as any other single factor, it determined how the war was fought and why it ended as it did. It was also complex, intense, and sprawling, born in controversy, and defined by all variety of contradictions, contours, and shadings. This is not to deny the generals and battles their due, but it is also true that the great campaigns often obscure as much as they reveal.

The guerrilla war began on the Confederate side as a spontaneous reaction to invasion. Large numbers of Confederates considered it a natural way to fight a war. After all, they said, the southern character favored brashness over caution, aggressive, independent action over a defensive, disciplined response to danger. Southern history also endorsed irregular warfare. Southerners recalled how “partizan” leaders of the American Revolution, such as Francis Marion and Thomas Sumter, had turned back British invasion of the South. So, as southerners again braced for invasion by vastly superior numbers, an important part of their collective memory associated military victory with a romanticized brand of partisan resistance. They would again be a nation in arms, every man with a rifle, every clump of rocks or trees a sniper’s nest.

Rebel leaders were not so sure. They knew the historical precedents for guerrilla warfare, but they also considered it a slightly dishonorable way to fight. Jefferson Davis and his chief military advisors had been educated in the nation’s military academies, most notably West point, where they had learned to think of wars in terms of grand, climactic, Napoleonic-style battles. They associated guerrilla combat not, as did the public, with romantic knights of the American Revolution, but with untutored, even uncivilized, peoples. Their experiences fighting Indians and Mexicans in the decades before the Civil War confirmed this prejudice. An extensive guerrilla war also seemed likely to undermine military discipline and cohesiveness, as well as to make the civilized nations of Europe, whose support the Confederacy would need in order to cinch victory, reluctant to aid the rebel cause.

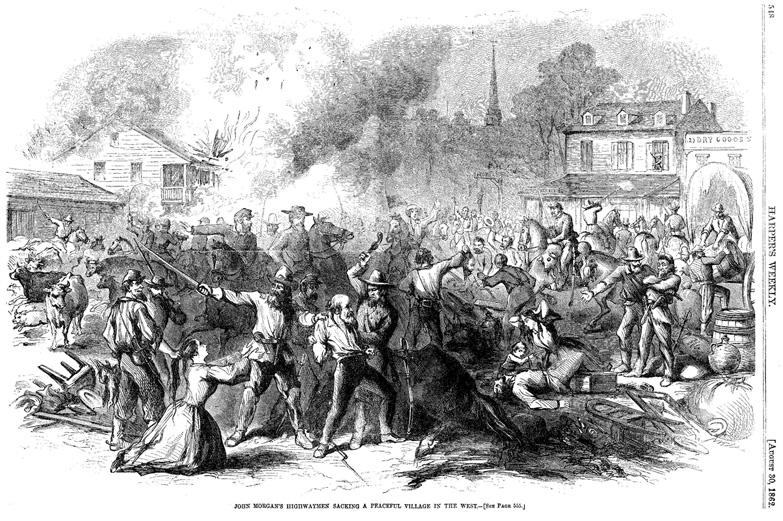

Even so, when forced to employ guerrillas in the early months of the war, Confederate leaders found them extremely useful. Guerrillas helped check invading armies at every turn. They distracted the Federals from their primary objectives, caused them to alter strategies, injured the morale of Union troops, and forced the reassignment of men and resources to counter threats to railroads, river traffic, and foraging parties. They shielded communities, stymied Union efforts to occupy the South, and spread panic throughout the lower Midwest. The politicians and generals could not have hoped for more, and so they vacillated, never fully endorsing their guerrillas but uncertain how best and how long to use them. History had shown that guerrillas could not win wars on their own, but rebel leaders knew not how to make them part of some broader plan.

This indecisiveness hurt the Confederates. Guerrillas grew increasingly independent and ungovernable, very nearly waging their own war. They also drew a devastating response from the enemy. Seeing the dangers posed by guerrillas to their own military operations, the Federals retaliated. They treated rebel guerrillas as brigands, not soldiers, and they punished rebel civilians who supported or encouraged guerrilla warfare. That was not all. As Union armies encountered an entire countryside arrayed against them–guerrillas in the bush, citizens cheering them on–U.S. military and political leaders realized that winning the conventional battles would not end the war. They must also crush rebellion on the southern home front. This revelation yielded profound changes in Union military policies and strategy. Those changes, in turn, produced a more brutal and destructive war that led eventually to Confederate defeat.

However, this was only the military side of the story. An equally important dimension of the guerrilla war was its social impact. First, southerners who opposed the Confederacy, the so-called Unionists, formed their own guerrilla bands and clashed with rebel neighbors in violent contests for political and economic control of their communities. These local struggles often caused people to lose sight of the conflicting national goals, whether Union or Independence, that had inspired the war. The need to maintain law and order reigned supreme. In places where Unionists gained the upper hand, or where rebel guerrillas could not ward off occupation by Union armies, the Confederate war effort splintered. Rebel citizens blamed the government for failing to protect them; winning distant battles became less important than preserving homes. Then the guerrilla war bred cancerous mutations. Violent bands of deserters, draft dodgers, and genuine outlaws operated as guerrillas to prey on loyal Confederates and defend themselves against rebel authorities. This broadened the South's internal war, and where deserters and draft dodgers made common cause with armed Unionists and slaves, anarchy prevailed.

By 1865, support for the Confederacy had eroded badly. People who had entered the war as loyal Confederates came to believe their government could not protect them. Surrounded by violence, all semblance of order–and with it civilization–seemed to collapse. People who originally looked to local guerrillas for defense blamed them for much of the ruin, but they also cursed the government. It was the government’s inability to protect them that had led many communities to rely on guerrillas in the first place. Then, as Union armies retaliated, and mutant forms of the guerrilla war engulfed them, those same people saw that their leaders could not control the upheaval. They lost their stomach for war.

In geographical terms, the spread of the guerrilla war followed a fairly predictable pattern. Viewed primarily as a defensive strategy, reliance on local guerrilla resistance coincided with the first appearance of hostile armies. This is why the guerrilla conflict began and was always most intense in the border states of Missouri, Tennessee, Virginia, and, in a delayed reaction, Kentucky. As Union armies then threatened Arkansas, northern Mississippi, northern Alabama, and North Carolina, the guerrilla war kept pace. This same pattern also fit, if not so exactly, local wars between Confederate and Unionist neighbors. Given that most white southerners were loyal to the Confederacy, at least through the first two or three years of the war, resistance by local Unionists became most intense with the arrival of Union soldiers in their communities.

Definitions are also important for understanding the guerrilla conflict. The name guerrilla is generally used to identify the participants in this irregular war, but it was not the only one. To start with, rebel guerrillas frequently preferred the eighteenth-century name of partisan, and indeed, for at least the first year of the war, the two names were interchangeable. Then, in the spring of 1862, the Confederate government used the name partisan, or partisan ranger, to identify its “official,” government-sanctioned guerrillas. Unlike regular guerrillas, who decided for themselves where, when, how, and against whom to fight, partisans were expected to obey army regulations and coordinate their movements with local military commanders. Generally mounted and organized in company or battalion-sized units, they operated on “detached service” to provide reconnaissance, conduct raids, and attack small groups of enemy soldiers.

Yet, beyond this fairly clear distinction between independent and official guerrillas, Civil War irregulars came in a variety of shapes, sizes, and persuasions. Bushwhackers represented a third general and very amorphous category. They were, strictly speaking, lone gunmen who “whacked” their foes from the “bush.” However, the name also became a pejorative term for anyone who seemed to kill people or destroy property for sport, out of meanness, or in a personal vendetta. It bore the taint of cowardly behavior. All of the outlaws, deserters, and ruffians who behaved like guerrillas fall into this category, but then many Union soldiers referred to all guerrillas as bushwhackers. And the list continues. Some guerrillas and partisans called themselves scouts, raiders, or rangers, and not a few home guards and militia companies operated as guerrillas. On the Union side, there were Red Legs on the Kansas-Missouri border, buffaloes in North Carolina, and jayhawkers, although jayhawker, like bushwhacker, gained more universal application. The Union army tried to define its wily rebel foes more precisely midway through the war, but the resulting list, which included bandits and marauders, did little to clarify matters. There was also much swapping of identities, with partisans often becoming mere guerrillas, and guerrillas calling themselves partisans or behaving like bushwhackers.

It must be said, though, that at least two things defined nearly all “guerrillas,” whatever they called themselves, whatever other people called them, or on whichever side they fought. First, there was the “irregular” way they attacked, harassed, and worried their foes, quite unlike the methods used by regular soldiers in conventional armies. Second, their principal responsibility, their very reason for being in most cases, was local defense, protection of their families or communities against both internal and external foes. Guerrillas often stretched and tested the second of these conditions, especially the rebels, and especially early in the war, when men volunteered from everywhere to halt the invasion of the Upper South. Still, even then, they considered defense of the Confederacy’s borders as tantamount to sparing their own states the enemy’s presence. If this is a somewhat elusive, ungainly, and untidy definition, it only reflects the nature of the guerrilla war.

The same elusiveness confounds efforts to determine the number of guerrillas. We know approximately how many men served in the Union and Confederate armies, but few documents, such as muster rolls and pension applications, have survived to tell us the number of guerrillas. Some thirty-odd years ago, Albert Castel, one of the first scholarly authorities on Civil War irregulars, estimated that as many as 26,550 Union and Confederate guerrillas participated in the conflict, but that number is surely low, perhaps by as much as half. Castel excluded Confederate partisans from his tally, calculated a mere 600 guerrillas as the total for six states, and estimated no more than 300 rebel guerrillas (missing the Unionists entirely) in all of Alabama and Mississippi. In truth, we do not even know how many bands of guerrillas operated during the war, much less the number of individuals. Besides, it may well be argued that precise figures are irrelevant. The central story of the guerrilla war is not so much the number of participants as their impact on military operations, government policies, and public morale.

If you can read only one book:

Daniel E. Sutherland, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Books:

Michael Fellman, Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the American Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Robert R. Mackey, The Uncivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861-1865. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.

Clay Mountcastle, Confederate Guerrillas and Union Reprisals. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009.

Jonathan Dean Sarris, A Separate Civil War: Communities in Conflict in the Mountain South. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006.

John C. Inscoe and Gordon B. McKinney, The Heart of Confederate Appalachia: Western North Carolina in the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Baron A. Myers, Executing Daniel Bright: Race, Loyalty, and Guerrilla Violence in a Coastal Carolina Community, 1861-1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009.

Daniel E. Sutherland, Ed., Guerrillas, Unionists, and Violence on the Confederate Home Front. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Thomas D. Mays, Cumberland Blood: Champ Ferguson’s Civil War. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2008.

Paul Christopher Anderson, Blood Image: Turner Ashby in the Civil War and the Southern Mind. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002.

James A. Ramage, Gray Ghost: The Life of Colonel John Singleton Mosby. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999.

James A. Ramage, Rebel Raider: The Life of General John Hunt Morgan. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1986.

Edward E. Leslie, The Devil Knows How to Ride: The True Story of William Clarke Quantrill and His Confederate Raiders. New York: Random House, 1996.

Albert Castel, William Clarke Quantrill: His Life and Times. New York: Frederick Fell, 1962.

Albert Castel and Thomas Goodrich, Bloody Bill Anderson: The Short, Savage Life of a Confederate Guerrilla. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books, 1998.

Jeffrey D. Wert, Mosby’s Rangers: The True Adventures of the Most Famous Command of the Civil War. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.