Prisoner Exchange and Parole

by Roger Pickenpaugh

Analysis of the prisoner exchange and parole system

The release of prisoners of war on parole actually predated the opening shots of the American Civil War. On February 18, 1861, after Texas seceded, Major General David Emanuel Twiggs surrendered all Union forces in the state to the Confederates. The officers and men were soon on their way north, carrying with them paroles stating that they would not serve in the field until formally exchanged. On April 14, 1861, the opening shots of the war were fired at Fort Sumter. The entire Union garrison was not only paroled to their homes, but the Confederates also provided them with transportation.

As contending forces headed into the field in the summer of 1861, commanders began negotiating individual exchange agreements. One of the first took place in Missouri, and it illustrated many of the concerns that would plague the exchange process in the future. Confederate Brigadier General Gideon Johnson Pillow made the first move. On August 28 he sent a message to Colonel William Hervey Lamme“W. H. L.” Wallace offering to exchange prisoners. Wallace replied by pointing out that the "contending parties" had not agreed to a general exchange and by emphasizing that any exchange to which he agreed would not be interpreted as a precedent.[1]

When Pillow, believing Wallace held a greater number of prisoners, proposed that Federals held in Richmond be included, Wallace declined. He also balked at Pillow’s suggestion to include civilian prisoners in the agreement. Wallace’s superior, Major General John Charles Frémont, added a stipulation that only regular soldiers would be accepted, no home guards. By the time all the restrictions had been put in place, each side received only three prisoners.

Brigadier General Ulysses S. (Hiram Ulysses) Grant was equally cautious when, on October 14, Major General Leonidas Polk proposed an exchange of prisoners. "I recognize no Southern Confederacy myself," Grant was quick to point out. Instead of negotiating any type of agreement, Grant simply returned three Confederates through the lines. The officer who conducted the captives to a flag-of-truce steamer received strict orders to avoid any formal discussions with Confederate officials. Polk responded by returning sixteen captured Union soldiers. The two continued the process for several weeks. Eventually the generals met face-to-face to expedite the exchange of 238 wounded captives. Grant was careful, however, to limit the scope of the talks to his corner of the war.[2]

Similar limited exchanges also took place in the Eastern Theater between individual commanders. The greatest number was arranged by Major General Benjamin Huger, commanding the Confederate Department of Norfolk, and Union Major General John Ellis Wool, who commanded Fortress Monroe. The two generals also arranged for clothing to be shipped to prisoners on both sides. However, like his Western counterparts, Wool never allowed the scope of the discussions to expand to the issue of a general exchange.

Wool’s caution reflected the policy of the Lincoln Administration, which was fearful of adopting any position which would in any way imply recognition of the Confederate government. Philosophically, Lincoln’s views were consistent. His reading of the Constitution led him to believe that the Union was "perpetual." As for secession, as he explained in his inaugural address, "Resolves and ordinances to the effect are legally void."[3]

The war soon raised questions more practical than philosophical. Lincoln learned this when his administration adopted a policy of treating captured Southern privateers as pirates rather than belligerents. In early November the crew of the Confederate brig Jeff Davis was convicted of piracy and sentenced to death in a Philadelphia courtroom. The Confederate president immediately came to the defense of those serving aboard his namesake vessel. Davis sent word through the lines that an equal number of Union prisoners had been selected for like execution in the event that the sentence was carried out. Putting philosophy aside, Lincoln backed down from what threatened to be a senseless blood bath.

Still, the Union president remained opposed to a general exchange agreement. He was, however, an adroit politician, sensitive to the rumblings of public opinion. As 1861 drew to a close, and reports of poor conditions in Confederate prisons reached the North, those rumblings became louder and more numerous. On December 11 a joint congressional resolution called on the administration to "inaugurate systematic measures for the exchange of prisoners in the present rebellion."[4]

Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton attempted to deflect the issue by attempting in January 1862 to send food, clothing, and other supplies through the lines. Methodist Bishop Edward Raymond Ames and New York Congressman Hamilton Fish agreed to run the operation. Wool received orders to secure passes for the emissaries. The Confederates, seeing a potential opportunity in the mission, sent two negotiators to Fortress Monroe to meet with Ames and Fish and attempt to secure an exchange cartel. The two men realized the Southern proposal went well beyond their instructions from Washington. They sought advice from Stanton, who instructed them to return home.

The president and his secretary of war nevertheless realized that they could not hold out much longer in the face of the public outcry for exchange. The same day that he recalled Ames and Fish, Stanton gave Wool authority to negotiate an agreement with Confederate Brigadier General Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb. The two could not agree on language, and the negotiations failed.

On June 23 the Senate adopted another resolution on exchange, and the New York Times, a paper usually friendly to Lincoln, editorialized, "Our government must change its policy, our prisoners must be exchanged!" On July 12 the administration decided to try again to reach an agreement. Stanton gave the assignment to Major General John Adams Dix, Wool’s successor at Fort Monroe. Confederate General Robert Edward Lee sent Major General Daniel Harvey Hill as the Confederate negotiator. This time things went smoothly. Following a series of meetings at Haxall’s Landing on the James River, the two generals reached an agreement on July 22.[5]

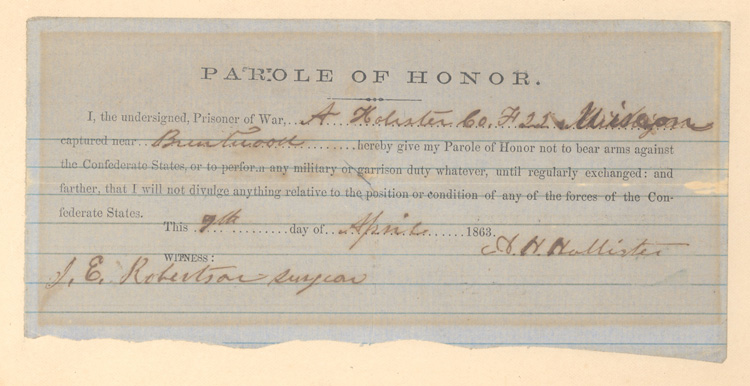

Patterned upon a similar arrangement used by the Americans and the British during the War of 1812, the Dix-Hill Cartel established a sliding scale to calculate the relative values of officers and enlisted personnel. Excess prisoners would be paroled and not permitted to take up arms until properly exchanged. The agreement called upon each side to appoint an agent of exchange to oversee the process. Finally, the terms stipulated that disputes were to be "made the subject of friendly expressions in order that the object of this agreement may neither be defeated or postponed."[6]

Four days after the cartel was signed, some 800 wounded Union captives left Richmond to begin the return journey north. Smaller numbers left over the next several days. On August 3 three thousand enlisted men bid goodbye to the Belle Isle Prison. Similar numbers departed from Richmond during the next two months. Meanwhile, prisons at Salisbury, North Carolina; Columbia, South Carolina; Macon, Georgia; and other points in the Confederacy also began to empty.

In the North, Colonel William Hoffman, the Union commissary general of prisoners, traveled from camp to camp to oversee the departure of Confederate captives. He started in the West, where the vast majority of Southern prisoners were held. Beginning August 22, he gave detailed instructions to commanders at Camp Morton, Camp Chase, Johnson’s Island, Camp Douglas, Camp Butler, and Alton, Illinois. The prisoners were sent away in detachments of about one thousand, each guarded by a company of Union soldiers. Most traveled by rail to Cairo, Illinois, then took Mississippi River boats to Vicksburg, the Western point of exchange. Captives destined for the Eastern Theater headed for Aiken’s Landing on the James River.

The Union prisons emptied dramatically. In July of 1862 there were 1,726 captives at Camp Chase. By the following March the number was down to 534. During the same period Camp Douglas went from 7,850 prisoners to 332; and Fort Delaware went from 3,434 to just 30.

Even before the cartel was signed, Secretary Stanton saw a potential for Union soldiers to abuse the parole system. The Confederates had begun paroling a number of Western prisoners unilaterally, including some two thousand taken at the April 1862 battle of Shiloh. They had also initiated a policy of paroling prisoners in the field. It did not take long for Billy Yank to realize that capture no longer meant months of confinement in a dreary Southern prison. Rather, its likely result would be a lengthy furlough and a trip home until exchanged.

On June 28 the War Department issued General Orders No. 72. The orders announced that furloughs would not be granted to paroled prisoners. Instead, parolees were to report to one of three parole camps established for their reception. Those from the East would go to a facility near Annapolis soon to be christened Camp Parole. Parolees belonging to Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Tennessee, Indiana, and Michigan regiments were ordered to Camp Chase near Columbus, Ohio. The War Department designated Benton Barracks, located near St. Louis, for paroled soldiers from Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri.

Benton Barracks was the first parole camp to receive large contingents of men. On July 13 Colonel Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville, commander of the post, reported that 1,167 had just arrived. They reached the camp "without officers and with extraordinary opinions of duties proper for them." Specifically, the soldiers insisted that the terms of their paroles precluded them from performing any military duties whatsoever. They refused to stand guard duty or to perform garrison duty. Bonneville disagreed, and many ended up in the guard house adorned by a ball and chain.[7]

Many did not bother to remain in the camp, opting instead for "French leave" and risking being charged with desertion. On February 1, 1862, Bonneville reported that there were 818 parolees at Benton Barracks and 971 reported absent.

To the east, paroled soldiers began arriving at Camp Chase in August 1862. By September 9 Ohio Governor David Tod was complaining to Washington, "It is with great difficulty we can preserve order among [the paroled soldiers] at Camp Chase." He suggested arming them and sending them to Minnesota to help quell an uprising of the Sioux Indians. Stanton liked the idea, and on the 17th he sent Major General Lewis “Lew” Wallace to Camp Chase to take charge of the parolees and organize them for a Minnesota campaign.[8]

The conditions Wallace found at the camp, recently a Union prison, appalled him. "They were stained a rusty black," he later wrote of the quarters, "the windows were stuffed with old hats and caps. The roofs were of plank, and in places planks were gone, leaving gaping crevices to skylight the dismal interior." Writing to Washington, Wallace reported that only two thousand of the five thousand men who were supposed to be there were present, "and if they have deserted they should not be blamed." Scores lacked shoes, socks, and breeches. "I assembled them on the parade ground and rode amongst them," Wallace wrote, "and the smell from their ragged clothes was worse than an ill-conducted slaughterhouse." Wallace concluded that the men were no better off than they would have been in a Confederate prison.[9]

Wallace attempted to make effective regiments of the demoralized troops, but the odds were against him. He established a new camp, dubbed Camp Lew Wallace, a few miles away. His plan was to march the men to Columbus to receive back pay then send them on to the new camp to be organized. This, Wallace believed, would separate the willing from the unwilling. Instead, the pay provided the parolees with the means to desert. In one instance, several men from one company fled down the side streets of Columbus, never reaching the new camp.

Those that remained, whether at Camp Chase or Camp Lew Wallace, proved little more cooperative. Neighboring farmers complained of missing fence rails and slaughtered hogs. As at Benton Barracks, the parolees resented orders requiring them to perform various military duties. "There is great dissatisfaction among the paroled men," an Ohio soldier informed his family. "Gen. Wallace requires them to perform camp duty, when their parole positively says they must not perform such duty until exchanged." The controversy was so great, he added, that there was "a prospect of it terminating in a battle." Another man seemed to confirm the prediction, writing in his diary, "Boys have been playing the Devil generaly. Burn the guard house. Whip all the officers who show their heads." As for himself, "I am getting tired of this playing soldier." [10]

Lew Wallace was getting tired of it too. On September 26 he begged Stanton not to send any more paroled men to Columbus. "It is impossible to do anything with those now in Camp Chase," he complained. "Every detachment that arrives only swells a mob already dangerous." On October 18 he announced that he had organized all the parolees into regiments. To make his point clear, he added, "Having thus discharged all the duties required of me at this post I have no doubt of being able to take the field, with a command suitable to my rank."[11]

The story was the same at Camp Parole. One of the first parolees to arrive there noted in his diary, "The officers tried to make us do guard duty around the camp but it was no go as we all hung together and would not do it." At least one officer was sympathetic with the men’s position. A Pennsylvania officer, "who has been in other wars," informed the men that performing "any duties for our government" would be a violation of the men’s paroles.[12]

Of more immediate concern to the parolees was their government’s failure to prepare for them. Rations were in short supply, adding insult to injury for men who had suffered at such Confederate prisons as Belle Isle. Many of the men turned to marauding. One diarist observed that the paroled soldiers spent their days roaming the countryside in search of apples, pears, peaches, and "everything they can lay their hands on." A banner blackberry crop supplemented many men’s rations. Others went fishing for crabs in Chesapeake Bay.[13]

Civilians and their crops were not the only victims of the marauding. "Law and order is not known, and crime goes unpunished," a New York soldier observed of the camp. Fights were common, particularly after dark. Robbery was often the motive. Sometimes the deeds were perpetrated by individuals, but gangs also roamed the camp, seeking out men who had recently received their pay.[14]

Colonel George Sangster, Camp Parole’s commanding officer, put much of the blame on liquor, which the men were able to purchase in Annapolis. When pay was issued in November, the result, according to one parolee, was "gambling, drinking & everything attending to a reckless demoralized collection of thoughtless beings calling themselves human." Sangster attempted to shut down saloons that sold to soldiers, as did his successor, Col. Adrian Root, with virtually no success.[15]

The most serious incident at Camp Parole occurred on September 22. The camp sutler, termed an "army vulture" by parolee, had constructed a dining hall and storehouse and secured a stock of goods reportedly valued at $15,000. A private went there for breakfast only to be told that officers would be served first. When the man objected, he was kicked out and placed under guard. Word of the incident quickly spread, and before long about a thousand angry soldiers were at the scene. They freed their comrade and proceeded to loot the establishment of food, cigars, tobacco, and anything else they could find. The sutler attempted to stop them until a champagne bottle thrown by one of the rioters struck him in the head. Guards sent to quell the disturbance were sympathetic to the men. The raiders did not quit until they had dismantled the store and carried off the lumber for tent flooring.[16]

Dispatched to Camp Parole to investigate reports of a lack of discipline, Colonel Hoffman conceded that there were a few "deficiencies," but overall considered the men well cared for. In his final report, Hoffman put most of the blame on the paroled men, writing, "The greatest obstacle in the way of a favorable state of things [at Camp Parole] is the anxiety of the men to go to their homes and their unwillingness to do anything to better their condition."[17]

Despite the blithe assessment he offered his superior, Hoffman realized that Camp Parole’s problems went deeper. To address them he ordered the construction of a new camp. Barracks would replace the tents in which the men were being housed. The camp would also be made more compact, which the commissary general believed would lead to improvements in policing and discipline. The men occupied the new barracks on September 1, 1863, just as the exchange cartel was collapsing.

Another parole camp opened after the capture of Harpers Ferry, Virginia and its 12,000 Union defenders by Confederate forces on September 15, 1862. The prisoners were quickly paroled and started for Annapolis, where they arrived following a tough four-day march. They soon learned that their stay at Camp Parole would be brief. On the 22nd the men were informed that they were bound for Chicago.

Some ended up at Camp Douglas, a Union training camp that had been pressed into service as a military prison. It was christened Camp Tyler, in honor of Brigadier General Daniel Tyler, the crusty old veteran placed in command of the paroled men at Chicago. Most were housed outside the camp in an area known as the Fairgrounds. Horse stables served as quarters for a large percentage of the parolees, with eight men crowded into the ten-by-fifteen foot stalls. Even these conditions led to few complaints at first. However, with the onset of cold weather and an increase in the sick list, the men’s patience was tried.

Rumors that they were to be sent to Minnesota to help fight Indians soured the parolees’ dispositions even more. On October 5 the Chicago Tribune published the terms of the exchange cartel. The men zeroed in on Article 6, which forbade the paroled soldiers from performing any "field, garrison, police, guard, or constabulary duties" until exchanged. After the article appeared, Tyler predicted, "I shall have hard work to keep our men quiet."[18]

Tyler’s prediction proved accurate. Soon the parolees were attacking the fence every night, the saloons and other attractions of Chicago proving to be a magnet to the soldiers. The guards proved powerless to stop them. The few who were willing to stand duty found their bayonets bent and the barrels of their weapons filled with sand or acorns. Others were physically attacked by the unruly soldiers. One night an enlisted parolee put on a captain’s uniform, gathered some friends, and marched the entire group to the guard line. The phony captain told the guards they were being relieved by a new regiment and ordered them back to quarters. After they departed, so did the supposed relief. When the sergeant of the guard came around with the legitimate relief guard, he found the line vacant.

In mid-October the men at Camp Douglas determined to destroy their camp by fire. The first broke out on the 17th. The blaze, aided by a strong wind, destroyed eleven barracks. It would have claimed more had volunteer axmen not worked quickly to tear down structures in the path of the flames. Four nights later a smaller fire claimed two buildings.

It was on the night of October 22, Tyler reported, that "the crisis came." He placed the blame on the Sixtieth Ohio, a unit that was so insubordinate that he placed the entire outfit under arrest. "To my great gratification," Tyler reported, "our paroled men with arms in their hands stood to duty and the Sixtieth Regiment caved in." Tyler brought in a company of the Sixteenth United States Infantry, with which he hoped to maintain order. "I claim this capitulation covers all the duties and I mean to enforce them," he concluded.[19]

Tyler’s assessment proved accurate. Over the next few days camp diarists recorded a few incidents of drunkenness and other violations, but nothing serious in nature. Meanwhile, Major General John Pope eased tensions even more by announcing that he had quelled the Sioux uprising in Minnesota. Soon the Chicago regiments were being exchanged, which further improved the parolees’ dispositions.

The main Confederate parole camp was first located at Demopolis, Alabama. On June 3, 1863, Maj. Henry C. Davis, the commanding officer, reported that the men were "very comfortably situated here, requiring no tents, as they occupy the Fair Grounds." However, many were also "in a destitute condition, having no clothes or money."[20] The numbers at Demopolis soon swelled, as did the problems. On July 4, 1863, Confederate commander Lieutenant General John Clifford Pemberton surrendered the garrison at Vicksburg, some 20,000 number. General Grant paroled all his prisoners. The Confederates gave the parolees a thirty-day furlough, after which time they were to report to camps in their home states. Those from Alabama were ordered to Demopolis.

The concerns the paroled men brought to Demopolis would have sounded familiar to Union officials. Many believed the terms of their paroles prohibited them from bearing arms, even for the purpose of drilling. Others asserted that they were exempt from all military service, including remaining at a parole camp until exchanged. On September 9 Brigadier General William Montgomery Gardner, then commanding at Demopolis, appealed to the War Department. "Up to this time there has been very little disposition evinced on the part [of] the paroled men to return to this point," Gardner quaintly reported. More bluntly, he continued, "I do not think they will come in in any large numbers unless some strong measures are adopted." Specifically, he called for the publication of "an order from an authoritative source."[21]

Gardner had a personal stake in making his appeal. Many of the men who should have been reporting to Demopolis had been serving under his command when he was forced to surrender Port Hudson, Louisiana after the fall of Vicksburg. Nevertheless, the order he called for would not be issued until January.

In the meantime, Lieutenant General William Joseph Hardee was placed in command of all Vicksburg and Port Hudson parolees. Hardee moved their rendezvous from Demopolis to Enterprise and attempted to appeal to their patriotism. "Soldiers," he declared on August 27, "look at your country! The earth ravaged, property carried away or disappearing in flames and ashes, the people murdered, negroes arrayed against whites... He who falters in this hour of his country’s peril is a wretch who would compound for the mere boon of life robbed of all that makes life tolerable." He appealed to the men, "Come to your colors and stand beside your comrades, who with heroic constancy are confronting the enemy."[22]

In November Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk succeeded Hardee and tried his own patriotic proclamation. "It is hoped," he declared on the 20th, "that the gallant men who, by their courage and heroic sacrifices, have made Vicksburg and Port Hudson immortal, will need no new appeals to induce them to make their future military history as glorious as their past."[23]

Perhaps the men did not see Vicksburg and Port Hudson in the same glorious terms that Polk did; or perhaps they sincerely believed their paroles released them from military duty until exchanged. Whatever the reason, Polk experienced the same problems the commanders before him had encountered. "It is contended by many of them that they are forbidden by that [parole] instrument from assembling in military camps at all, or performing any military duty whatever," he informed the War Department, "and holding that construction they refuse to come into camp or attempt to leave at their pleasure." Many had crossed the Mississippi and gotten beyond his authority. Like Gardner before him, Polk called for stern orders from the War Department.[24]

Although the exchange cartel freed thousands of prisoners, and likely saved the lives of a large percentage, the agreement was doomed to failure. The disagreements surfaced early. On October 5, 1862, Robert Ould, the Confederate agent of exchange, sent a list of nine grievances to Lieutenant Colonel William Handy Ludlow, his Union counterpart. Some of the issues were minor. For example, Ould complained of the small numbers of exchanged men who arrived aboard some flag-of-truce boats. Most of his points concerned citizens or irregular troops held in close confinement. Ould concluded, "I do not utter in the way of a threat, but candor demands that I should say that if this course is persisted in the Confederate Government will be compelled by a sense of duty to its own citizens to resort to retaliatory measures." Of course it was a threat, and it was not the last made by either side.[25]

The issue that eventually ended the cartel was that of black soldiers. In July 1862 congress gave the president authority to accept blacks into the army. Following the Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect the following January 1, many were recruited. Nearly 200,000 served during the course of the war.

The Union policy was greeted with outrage in the South. On May 1, 1863, that outrage was codified by the Confederate congress. A joint resolution declared that captured black soldiers would be turned over to the states and presumably returned to slavery. Their white officers would be "deemed as inciting servile insurrection, and shall if captured be put to death or otherwise punished at the discretion of the court."[26] Ludlow’s response was vociferous. He termed the resolution "a gross and inexcusable breach of the cartel in both letter and spirit" and reminded Ould that color was never mentioned in the agreement. He concluded, "I now give you formal notice that the United States will throw its protection around all its officers and men without regard to color and will promptly retaliate for all cases violating the cartel or the laws and usages of war."[27]

Ludlow’s threats were soon made into formal Union policy. On May 25 orders went out to all department commanders that no Confederate officers were to be paroled or exchanged. On July 13 Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered that no more prisoners of any rank be delivered to City Point, Virginia for exchange. Ludlow believed this order went too far. When he protested, he was relieved and replaced by Brigadier General Sullivan Amory Meredith, who took a hard line in his negotiations with Ould.

The Union’s true motives in rendering the cartel a dead letter have long been the subject of speculation and debate among historians. Victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg had left the Union in a much stronger position militarily. They also left the North with an advantage in the numbers of prisoners held.

General Grant would soon become general-in-chief and a determined foe of exchange. In an oft-quoted message, he would assert, "It is hard on our men held in Southern prisons not to exchange them, but it is humanity to those left in the ranks to fight our battles. Every man we hold, when released on parole or otherwise, becomes an active soldier against us at once either directly or indirectly. If we commence a system of exchange which liberates all prisoners taken, we will have to fight on until the whole South is exterminated. If we hold those caught they amount to no more than dead men."[28]

At the same time, there is nothing in the documentary evidence indicating that the Union government was motivated by anything beyond a concern for the fate of its black soldiers. Stanton’s annual report to the president cited the South’s refusal to exchange black captives as the cause of the collapse of the cartel. Southern leaders at the time and some historians since have insisted that the North’s advantage in manpower was the true motive. The South would never, however, test this theory by offering to exchange black troops. Rather, Ould asserted, the Confederates would "die in the last ditch" before conceding that point.[29]

The strongest evidence that the Union government had no interest in resuming the cartel came in late 1863 when Major General. Benjamin Franklin Butler was named the North’s special agent of exchange. As military governor of Louisiana, Butler had been labeled the "Beast" by Southerners outraged by his actions. Among them was the hanging of a man who had hauled down an American flag. On another occasion Butler announced that any woman who insulted Federal soldiers would be "regarded and held liable to be treated as a woman of the town plying her avocation."[30] Despite the South’s enmity, the publicity-hungry general worked hard to arrange a resumption of the cartel. Working in his favor was the fact that 1864 was a presidential election year, and the public clamor for exchange was as strong as ever. On September 9 Butler and Ould agreed to occasional exchanges of sick and wounded captives who would remain unfit for duty for at least sixty days.

Transports delivered many of the Union parolees to Camp Parole. Two years earlier paroled prisoners had few kind words for the Maryland facility. However, to men who had spent time at Andersonville and other Southern pens, it was a paradise. They received clean clothes, hearty meals, and a certain freedom of movement. As one former Andersonville prisoner observed, "This is a nice camp-- something like living."[31] Many of the men sent from Northern camps started too late for home. Of the five hundred sent in the first detachment from Elmira, thirty died en route. Many others arrived close to death. Some of the blame rested with the Northern Central Railroad, which took forty hours to deliver the men, crammed into boxcars, the 260 miles to Baltimore. Still, Josiah Simpson, Baltimore’s medical director, believed officials at the prison bore the bulk of the responsibility. "The condition of these men was pitiable in the extreme," he reported, "and evinces criminal neglect and inhumanity on the part of the medical officers making the selection of men to be transferred." Visiting the steamer that was about to deliver the prisoners to the Confederacy, Simpson found forty men who were so feeble that he felt they should not be allowed to travel. However, he heeded their pleas to be allowed to continue on toward home.[32]

There matters remained until early 1865. By then Grant had ridded himself of Butler and was largely handling exchange negotiations himself. The Confederacy’s days were clearly numbered, allowing the general-in-chief to moderate his previous position. On January 13 he approved a Confederate proposal for the release of all prisoners held in close confinement. Then, on February 2, Grant suddenly informed Stanton that he was making arrangements to exchange about 3,000 prisoners a week. Still, he had not totally abandoned his practical concerns. He insisted that Confederates from states firmly under Union control and captives unfit for duty be exchanged first.

In one instance Grant’s practicality went too far even for Stanton. At most Union prisons large numbers of captives did not want to return to the Confederate army. Some camp commandants honored their wish not to be exchanged. Hearing of this, Grant insisted that it made sense to return unwilling Rebels first. However, General Henry Halleck, Lincoln’s military chief of staff, concluded that it was "contrary to the usages of war to force a prisoner to return to the enemy’s ranks." This view became Union policy, and orders went out to all commandants against sending away prisoners who preferred not to be exchanged.[33]

For thousands of captives exchange did not come soon enough. At the Confederate prison at Salisbury a burial sergeant recorded 3,406 deaths from October 1864 through January 1865. The toll was also high at the Florence, South Carolina prison. One of the sad ironies of the war is the fact that February 1865, when general exchanges were resumed, was also the month that the number of deaths peaked at the eight largest Union prisons. The toll was 1,646, including 499 at Camp Chase alone. Many had been captured during Lieutenant General John Bell Hood’s disastrous Tennessee campaign. Large numbers arrived at various camps ill, shoeless, and nearly naked.

Those who survived did not have long to wait before the final release came. Eager to get out of the prison business, the government emptied its depots quickly when the war ended and worked hard to return Union captives from the South. Sadly this ultimate exchange came only after the deaths of over 30,000 Yankees and more than 25,000 Rebels in Civil War prisons.

- [1] United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series II, volume 1, 504-505. (hereinafter cited as O.R., II, 1, 504-505)

- [2] O.R., II, 1, 511.

- [3]Philip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln. (Lawrence KS: University of Kansas Press, 1994), 53.

- [4] O.R., II, 3, 157.

- [5] New York Times, June 23, 1862.

- [6] O.R., II, 4, 265-268.

- [7] O.R., II, 4, 191.

- [8] O.R., II, 4, 499.

- [9] Lew Wallace, Lew Wallace: An Autobiography. (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1906), Vol. 2, 632-633; Lew Wallace to Lorenzo Thomas, September 21, 1862, Letters Sent from Headquarters, U.S. Paroled Forces, Columbus, Ohio, Record Group 393, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

- [10] Abner Royce to parents, October 3, 1862, Royce Family Papers, Mss. 1675, Western Reserve Historical Library, Cleveland; William L. Curry Diary, November 6, 1862, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- [11] O.R., II, 4, 563; Wallace to Thomas, October 18, 1862, Letters Sent from Headquarters, U.S. Paroled Forces, Columbus, Ohio, Record Group 393, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

- [12] Henry N. Bemis Diary, July 24, 1862, Musselman Library, Gettysburg College, Gettysburg, PA; Jerome J. Robbins Diary, July 26, 1862, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- [13] Simon Hulbert Diary, September 20, 1862, New York Historical Society.

- [14] William Harrison to "Cousin Frank," November 29, 1862, William Harrison Letter, Accession 40494, Personal Papers Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- [15] Robbins Diary, November 13, 1862, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- [16] Ibid., September 22, 1862.

- [17] O.R., II, 5, 6; O.R., II, 5, 348.

- [18] O.R., II, 4, 600.

- [19] Ibid., 644-645.

- [20] O.R., II, 5, 967.

- [21] O.R., II, 6, pp. 273-274.

- [22] Ibid., 232-233.

- [23] Ibid., 542-543.

- [24] Ibid., 6, 558.

- [25] O.R., II, 4, 602.

- [26] O.R., II, 5, 940.

- [27] O.R., II, 6, 17-18.

- [28] O.R., II, 7, 607.

- [29] O.R., II, 6, 226.

- [30]Patricia L. Faust, ed., Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War. (New York: Harper & Row, 1986), 840.

- [31]Henry H. Stone Diary, December 17, 1864, Andersonville National Historic Site, Andersonville, GA.

- [32] O.R., II, 7, 894.

- [33] O.R., II, 8, 239.

If you can read only one book:

Pickenpaugh, Roger, Captives in Blue: The Civil War Prison of the Confederacy. Tuscaloosa AL: University of Alabama Press, forthcoming.

Books:

Gillespie, James M., Andersonvilles of the North: The Myths and Realities of Northern Treatment of Civil War Confederate Prisoners. Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, 2008.

Hesseltine, William Best, Civil War Prisons: A Study in War Psychology. Columbus OH: The Ohio State University Press, 1930.

Levy, George, To Die in Chicago: Confederate Prisoners at Camp Douglas 1862-65. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 1999.

Speer, Lonnie R., Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1997.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

Roger Pickenpaugh Books. This website includes information on the author’s books and speaking engagements.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.