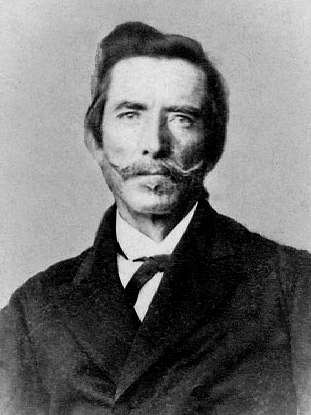

Raphael Semmes and the CSS Alabama

by Stephen Fox

Raphael Semmes took his swift commerce raider CSS Alabama on a 22 month rampage that captured 65 and burned 52 Union merchant ships and sank 1 Union warship.

Raphael Semmes was the first and most important Confederate naval hero. In one of the great feats in the history of naval warfare, he took his swift commerce raider, the CSS Alabama, on a 22-month rampage through the Atlantic and Indian oceans, hunting Union merchant vessels. He captured 65 of them, burning 52, and sank a Union warship as well. Semmes and his ship thereby generated rippling impacts on Northern morale and commerce, Southern war expectations, wartime (and postwar) diplomatic relations between the United States and Great Britain, and the long term prospects of the American merchant marine. All this from one rather small ship on the immense ocean!

Semmes had grown up on the border between North and South, and his eventual zeal as a Confederate patriot developed slowly over decades. He came from a well-established Roman Catholic family in Maryland. For generations his ancestors raised tobacco and owned slaves in Charles and St. Mary’s counties in the southern part of the state. Orphaned at age fourteen, Semmes joined the US Navy three years later as a midshipman. He spent 35 years in the Navy, often frustrated by the slow pace of promotion in peacetime. During extended leaves on shore he became a lawyer to augment his naval salary. He married a woman from Cincinnati, Anne Spencer, an anti-slavery Protestant. They had five children.

His marriage and naval service pushed Semmes toward national over regional loyalties. The Mexican War extended this process. For fifteen months he served in various capacities in the eastern theater, notably in the Marine invasion of Vera Cruz. Afterward he wrote an excellent history of the conflict, Service Afloat and Ashore During the Mexican War. [1] Critical at some points, fair in its judgments, the book still celebrated the easy US victory and the ongoing national march across the continent. “A work of standard merit,” Harper’s Magazine enthused. “We congratulate the noble-spirited author on the signal success of his work.”[2]

For Semmes and his wife the war also had harsher impacts. While he was fighting in Mexico, Anne risked an affair and became pregnant. She delivered a baby girl shortly after Semmes returned from the war. As a devout nineteenth-century Roman Catholic, he could not consider divorce. They remained married. At some point the child was dispatched to a distant convent school in Philadelphia. (Later, with her husband absent for years during the Civil War, Anne brought her back into the family home.)[3]

As though to compensate for his national service and Northern wife, Semmes moved his household to the Deep South, near Mobile, Alabama. He spent the 1850s in professional frustration, denied the commands of fighting ships that he thought he deserved. In 1858 he reluctantly took a desk job in Washington as secretary of the lighthouse board in the Treasury Department. Living and working in the national capital, he could observe at close hand the flailing politicians who were driving the nation toward a catastrophe.

In general Semmes agreed with Southern positions on slavery and states’ rights, and he accepted the widespread Southern notion that North and South comprised two incompatible cultures: Puritan, industrial, and Saxon against cavalier, agrarian, and Norman. But he did not think these differences required secession and war. In the showdown presidential election of 1860, he voted for Stephen Douglas, the relative centrist in the field.

His detachment meant that Semmes would be carried along by events, his decisions shaded by the most recent news. When seven Deep South states seceded in December, he remained at his federal job in Washington, expressing Southern sympathies but waiting for a job in the putative Confederate Navy. Finally the decision was made for him: on February 14 he was summoned to naval duty for the provisional government in Montgomery, Alabama. Prodded by the tumbling chaos of events, Hamlet suddenly became Hotspur. “The rude, rough, unbridled, and corrupt North,” he wrote in May, “threatens us with nothing less than utter subjugation.”[4]

Semmes urged the incipient Confederate Navy to engage “a small organized system of private armed ships, known as privateers.”[5] A traditional weapon of weaker nations against stronger ones, privateers had been well deployed by the United States in its two wars against Great Britain. But they operated in murky shadows as freelancers outside normal naval chains of command, capturing prizes and selling them for easy profits. “They are little better than licensed pirates,”[6] Semmes himself had declared in his Mexican War book. Now he saw a similar role for himself—but as the duly authorized captain of a commerce raider in the Confederate Navy, not as a freelance privateer. To the Lincoln administration, which did not recognize the Confederate government, Semmes was always nothing better than a pirate.

In New Orleans he took command of the CSS Sumter, a leaky little steamship plying the run down to Havana. After refitting she became the first oceangoing ship of the Confederate Navy. During six months of roaming the Caribbean and the North Atlantic, Semmes caught eighteen Union merchantmen, burning seven of them. In January 1862 the Sumter limped into Gibraltar, utterly worn out, its service ended. Semmes was soon promoted to a better, bigger, faster ship.

The vessel that became the CSS Alabama was then nearing completion at the Laird shipyard in England, across the river Mersey from Liverpool. No American shipbuilder of the time could have produced so fine a vessel. For decades, British naval architects and marine engineers had more quickly seen the advantages of screw propellers and iron hulls over the wooden paddle wheelers still favored by American builders. Thirty years earlier, John Laird had helped pioneer iron hulls in Britain. But the Alabama was expected to spend its career at sea, encountering uncertain port facilities, and a wooden hull was much easier to repair. So the Lairds crafted this ship of tough English oak.

The Alabama was uncommonly beautiful. In profile it resembled one of the crack American clipper ships of the 1850s: 220 feet long, 32 feet wide, with a sharply-cut clipper bow, three masts raked backward, an undercut “champagne” stern—and a stubby single smokestack that could be lowered for disguise. To blend into the ocean, the ship rode low in the water, and the hull, masts, lifeboats, and other fittings were all painted black. The steam engine produced 300 horsepower for special occasions of pursuit or flight. A crucial steam condenser distilled enough freshwater for the crew to remain at sea for months at a time. Six broadside cannon and two pivot guns, mounted amidships, proclaimed the Alabama a bristling vessel of war.

The ship was built under false pretenses. By law, no British shipyard was supposed to provide warships to a combatant in the American Civil War. But Liverpool was a stronghold of Confederate sympathy in Britain, and everyone there knew the Lairds were building a special warship for the secessionists. It was so obvious that the matter needed no discussion, indeed required a discreet, evasive silence. The U.S. consul in Liverpool, Thomas Dudley, tried to stop the ship with depositions and legal flurries. Through a tangled process that still remains quite mysterious, the Alabama was allowed to escape to sea in late July 1862.

Semmes, his new ship, and a supply ship from London reconnoitered in the Azores. With Confederate naval officers and barely enough British crewmen, the ship was formally commissioned. They went hunting near the Azores. In two weeks in early September, they caught and burned ten Union vessels, mostly New England whalers. Nobody was killed or injured. The Alabama, swifter than any whaler or merchant vessel, easily overtook the prey. A pattern then emerged: The Union officers and crews were transferred to the Alabama; a boarding party searched the captured ship for anything useful, then set it ablaze; the captured men were soon put ashore or transferred to a passing ship. In two months the Alabama burned twenty prizes, an average of one every three days.

Given that blazing start, Semmes and the Alabama made their historical reputations during the first five months of the cruise. From the Azores they shifted to the heavily trafficked shipping lanes off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, taking major merchant ships from Boston and New York. “Can one vessel do as she pleases on the high seas,” asked the New York Herald, the largest newspaper in the US, “and we, with all our resources of ships, guns, men and money, be unable to prevent it?”[7] Semmes kept showing up somewhere he was not supposed to be. Off Cuba in December, he took the passenger steamer Ariel with its 500 passengers (but had to release the ship on bond because the Alabama had no room for so many captives). A month later, in the Gulf of Mexico near Galveston, he sank the Union gunboat Hatteras, killing two of its crew—the first deaths of the cruise. “He does everything with a daring and a celerity that have rarely been surpassed,” the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin said of Semmes. “Cannot some one of our naval commanders show himself a match for the pirate? It is disgraceful.”[8]

Most of the historical literature on Semmes and the Alabama has been drawn from the readily available internal sources: shipboard journals kept by Semmes and Master’s Mate George T. Fullam, both later published, and memoirs written after the war by Semmes and two of his officers, John McIntosh Kell and Arthur Sinclair. External sources—the impressions of outsiders who were brought aboard—have been relatively ignored, in part because they appeared in less accessible places such as newspapers, manuscript collections, and obscure government documents. The internal sources describe a well-regulated ship, tidy and ordered, sending proper boarding parties to captured prizes. The external sources—mostly from Union viewpoints—describe a truly piratical atmosphere of sloppy discipline, filthy conditions, and boarding parties that routinely got drunk and larcenous. The truth presumably lies somewhere between the two versions.

Of all the Confederate commerce raiders, the Alabama had by far the most impact on the conduct of the war because of when and where Semmes and his ship were most effective. From the fall of 1862 through the spring of 1863, the Confederate land forces notched a remarkable string of wins. Paired with the recurring good news about the Alabama at sea, these successes pushed Southern hopes to a peak of optimism, with reasonable expectations that the war would soon end in victory. During those first five months of the cruise, Semmes generally stayed close to the US coastline. The news of his exploits therefore quickly reached Union newspapers, and his released captives came home and told lurid stories to the press, further stoking the new legend of the Alabama. Other Confederate cruisers took prizes later on—but so far from the US, or so late in the war, that they did not affect the conflict.

Gideon Welles, the US navy secretary, was forced to divert major resources to a hapless, hopeless pursuit of Semmes and his ship. Welles sent seven of his warships to chase the Alabama, then two more, then three more: a dozen Union steamers burning coal, time, and money to catch one marauding cruiser. Instead of trying to guess where Semmes might appear next, his pursuers instead went to where he was last reported—and thus arrived long after he had disappeared to somewhere else. The pursuing force reached fourteen vessels, then eighteen. The Union naval blockade of the Confederacy became even more porous. “It is annoying,” Welles wrote in his diary, “when we want all our force on blockade duty to be compelled to detach so many of our best craft on the fruitless errand of searching the wide ocean for this wolf from Liverpool.”[9]

For the Union merchant fleet, marine insurance companies tripled and quadrupled their “war risk” surcharges to 4 to 6 percent beyond the usual marine rates of around 8 percent of the total value of ship and cargo. That surcharge eventually reached 10 percent. Many ship-owners therefore carried no insurance at all, risking a total loss, or sold their vessels into foreign ownership, mainly British, knowing that should protect them from the terrible Semmes. The American merchant fleet was dealt hammer blows from which it has never quite recovered.

The states of the Confederacy had, compared to the North, no long tradition of oceangoing commerce. Southern steamships were mainly restricted to river and coastal traffic. The startling news of the Alabama in the fall of 1862 pushed some thoughtful Southerners to a fundamental rethinking of Dixie’s role in the world. “If Northern commerce upon the ocean could be destroyed,” the Richmond Dispatch mused, “or even to any great extent crippled, we should do the Lincoln empire more damage, at less cost, than by any land invasion of their territories.”[10] The Alabama had wreaked so much harm so cheaply—a persuasive bargain.

Good news about Semmes and his ship kept coming. “The Alabama at intervals electrifies the South by one of her daring and splendid exploits,” said the Richmond Examiner after the Hatteras was sunk off Galveston. “Glorious and gratifying as are the performances of the Alabama, they are in fact but reproaches to us, when we consider the splendid field of enterprise which she alone has dared to enter.” The Jefferson Davis administration, the Examiner insisted, should have deployed an entire fleet of fast cruisers. “Captain Semmes is still demonstrating that the true theatre for Southern raids is the great ocean.”[11] Carried to its logical conclusion, this proposition would have fundamentally redefined an agrarian, inward-looking nation into a commercial, outward-looking polity suited to the progressive nineteenth century. But the South could not transform itself in the middle of a war, and Davis was immune to suggestions.

Meantime the shadow games of the Alabama’s construction and release from Liverpool were driving the US and British governments toward, perhaps, the third Anglo-American war in less than a century. Charles Francis Adams, the besieged US minister in London, peppered the British Foreign Office with protests and warnings about the cruiser. Since the ship was illegally built, equipped, and mostly manned from England, Adams demanded British payments for Union shipping losses. The Foreign Office denied any British responsibility and gave Adams no satisfaction whatever. “The subject which presses most upon me just now,” Adams noted in December 1862, “is the controversy with this Government about the Alabama.”[12] The squabbling continued through the war and beyond, keeping the two nations on the edge of a persistent crisis.

After the extraordinary first five months of the cruise, Semmes and the Alabama sailed into a long afterlife. They roamed the Caribbean, lighting bonfires, and then headed for the high-traffic shipping lanes off the northeast coast of Brazil. There in ten days they caught four prizes, in particular the Sea Lark on May 3: with its ship and cargo valued at $550,000, the richest prize the Alabama ever took. Knowing that Welles’s gunboats would soon descend on the Brazilian coast, Semmes set a course eastward for the other side of the world, off Indonesia and Southeast Asia. In that lush nexus of Union merchant shipping, far from any hostile gunboats, the captain hoped for easy pickings.

On the way they stopped at Cape Town in South Africa. Their reception in that Anglo-Dutch colony, after a year at sea, brought the cruise to its climax. The British colonists giddily embraced the ship and its men. For a local newspaperman Semmes recounted his achievements: 54 captures since the previous September, an average of more than one a week, for a total estimated value of burned ships and cargoes of $4.2 million. Though he did not make the claim, his ship was already the most effective commerce raider in the annals of naval warfare.

This outward success masked grave internal concerns. At sea Semmes always had to keep his boiler fires banked, not extinguished, in case he needed sudden, emergency steam power. That prevented routine maintenance of the boilers, which had become leaky, encrusted with scale, and less efficient. The hull below the waterline had grown a thick, shaggy overcoat of plants and marine organisms which hobbled the fast cruiser and its frightening reputation for speed. Semmes himself felt old and worn out at age 54. “I am supremely disgusted with the sea and all its belongings,” he complained to his journal. “The fact is, I am past the age when men ought to be subjected to the hardships and discomforts of the sea....The very roar of the wind through the rigging, with its accompaniments of rolling and tumbling, hard, overcast skies, etc., gives me the blues.”[13]

With little enthusiasm, they embarked on the 5000-mile course across the southern Indian Ocean. “A weary, monotonous, and boisterous voyage,”[14] Lieutenant Arthur Sinclair later recalled. They went three long, blank months without a single capture. Bored and restless, the crewmen became nearly mutinous. Back in the Azores in August 1862, Semmes had dangled the lures of prize money, exciting naval battles, and roistering liberty on shore to recruit his crew of British sailors. In fact they had been given no prize money, just the one battle with the Hatteras, and infrequent, unsatisfying shore leave. The justifiably aggrieved mutterings in the forecastle would eventually endanger the cruise.

They reached Indonesia in late October 1863. The long prize drought finally ended on November 6 as they took the bark Amanda of Bangor, Maine. But in the next seven weeks of cruising around the East Indies, Semmes managed only two more captures. He had done his job too well: by this time too many Union merchant ships were either hiding in port or sold into foreign ownership. His quarry had largely disappeared from the ocean.

Facing few options, none of them appealing, Semmes decided to turn around and return to the Atlantic Ocean, the site of his best hunting. It was a slow slog of two months and, again, no prizes. The Alabama needed major overhauling in a European port equipped to repair the boilers and machinery. They stopped at Cape Town in March, but it seemed anticlimactic after their extravagant reception seven months earlier. Semmes took two final prizes near Cape Town—and then nothing at all for the final three months of the cruise.

Running down, exhausted and worn, in June they pulled into Cherbourg, across the channel from the English coast. “And thus,” Semmes wrote in his journal, “thanks to an all-wise Providence, we have brought our cruise of the Alabama to a successful termination.”[15] As repairs and coaling began, news of the famous cruiser’s appearance spread quickly. The US minister in Paris notified the Union gunboat USS Kearsarge, trolling off the Netherlands. The Union ship arrived at Cherbourg two days later, anchoring outside the harbor and blocking the Alabama. Semmes, with no realistic alternatives, announced that he would come out and fight when his preparations were finished.

The battle took place on Sunday, the 19th of June. After 22 months at sea, the Alabama’s powder and fuses were weakened by long exposure to ocean dampness and steam from the freshwater condenser, located adjacent to the powder magazine. Because of nearly-mutinous conditions among the crew, in recent months the Alabama had also neglected gunnery drills. The Kearsarge, just overhauled in London, had new boilers, a clean hull, and well-practiced gun crews.

The two ships were about the same size, but the Yankee had two big Dahlgren cannon that fired solid shot weighing 160 pounds, heavier and more penetrating than any of the Confederate’s ammunition.

So the fight was quite unequal. Semmes hoped to approach the Kearsarge, grapple and board it, but the Yankee was too nimble and skipped away. The two ships settled into a circular pattern, starboard to starboard, firing at each other across a distance of 400 to 900 yards. Shots from the Alabama sounded muffled and dull, with thick smoke like heavy steam; those from the Kearsarge cracked clear, sharp explosions that burned off into a thin vapor. The booming Dahlgrens did most of the damage. A shot crippled the Confederate’s rudder; another broke into the engine room at the waterline and exploded. The Alabama trembled from stem to stern, as though recoiling from that gaping mortal wound, large enough to swallow a wheelbarrow. The rising water snuffed out the boiler fires, cutting off steam power and disabling the pumps.

The Alabama settled at the stern. The bow went up and the ship went down after a battle of only 70 minutes. Under suspicious circumstances, a hovering English yacht, the Deerhound, plucked Semmes, John Kell, and twelve other officers—and 27 more Alabama crewmen—from the water and took them to safety in Southampton, across the channel. The Kearsarge had suffered minor damage and only three wounded men, one of whom died three days later. The Alabama counted nine killed in action, sixteen drowned or lost afterward, and one man who died of his wounds on the Kearsarge. With 21 men wounded as well, the Alabama took 47 casualties in all—almost a third of the ship’s company.

In London, Semmes recuperated with friends and pursued an apparent flirtation with a woman named Louisa Tremlett: a wartime romance like his wife Anne’s back in 1847, inspired and enabled by the unique, temporary upheavals of war.[16] Worried by Union agents in England, on July 30 Semmes, Tremlett, and four other friends fled for almost seven weeks on the Continent. The tour was a restful, romantic, sybaritic interlude after those hard, lonesome, dangerous years at sea. Finally, on October 3, Semmes left London for home.

The journey, routed carefully for security reasons through Cuba, Mexico, and Texas, took more than two months to reach Mobile. After his tumultuous services on the Sumter and Alabama for three years, Semmes quite reasonably believed that he had completed his war duties. Instead he was summoned to Richmond for sad, pointless assignments as the war wound down. Again he then returned to Mobile, in his second and final homecoming of the war. When he reached home, Anne was out in the family vegetable patch, hoeing with three former slaves.

For Semmes, as for many beaten Confederates, the war was not over. After retrieving his Sumter and Alabama journals from England, he wrote Memoirs of Service Afloat, During the War Between the States, an 833-page tome published in 1868. It screamed one long cry of stubborn, righteous refusal to admit defeat. In that spirit, he revised his own record on the touchy issue of slavery as the cause of the conflict. On the Sumter in 1861, he had noted that “we were fighting the first battle in favor of slavery.”[17] After the war, as the myth of the Lost Cause gained credence, Semmes insisted in his book that the South was actually fighting for its independence and freedom, in the noble revolutionary spirit of 1776, and not for slavery. Aside from that blatant rewriting of his personal history, Memoirs of Service Afloat remains one of the finest, fullest accounts by a major participant in the war. Considered just on its literary merits, the book is far deeper, wider, and better written than many more acclaimed Civil War memoirs.

As time passed, Semmes began to accept the outcome of the war. He finally came down from his perch on the horse block of the Alabama. “Men’s opinions are what circumstances make them,” he wrote in 1872, “and if the people of Boston had been born in Mobile, and the people of Mobile in Boston, there can be little doubt, that they could have reciprocally exchanged opinions. This reflection should moderate our human pride, and teach us charity.”[18] Indeed.

He died in August 1877, a few weeks short of his sixty-eighth birthday.

Raphael Semmes

- [1] Raphael Semmes, Service Afloat and Ashore During the Mexican War (Cincinnati, OH: Wm. H. Moore & Company, 1851).

- [2] “A Work” Harper’s Magazine, October 1851.

- [3] Stephen Fox, Wolf of the Deep: Raphael Semmes and the Notorious Confederate Raider CSS Alabama (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007), 30-2.

- [4] Fox, Wolf of the Deep, 39.

- [5] Ibid.

- [6] Semmes, Service Afloat and Ashore, 82.

- [7] New York Herald, November 3, 1862.

- [8] Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, January 27, 1863.

- [9] Fox, Wolf of the Deep, 98.

- [10] Richmond Dispatch, October 31, 1862.

- [11] Richmond Examiner, January 23, 1863.

- [12] Fox, Wolf of the Deep, 119.

- [13] Fox, Wolf of the Deep, 174.

- [14] Ibid., 175.

- [15] Ibid., 208.

- [16] Fox, Wolf of the Deep, 230-3, 250-3.

- [17] Ibid., 249.

- [18] Ibid., 255.

If you can read only one book:

Fox, Stephen. Wolf of the Deep: Raphael Semmes and the Notorious Confederate Raider CSS Alabama. New York: Knopf, 2007.

Books:

Bowcock, Andrew. CSS Alabama: Anatomy of a Confederate Raider (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002).

Kell, John McIntosh. Recollections of a Naval Life Including the Cruises of the Confederate States Steamers (Washington, D.C.: Neales Publishing Company, 1900).

Marvel, William. The Alabama and the Kearsarge: The Sailor’s Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1996).

Semmes, Raphael. Service Afloat and Ashore During the Mexican War (Cincinnati, OH: Wm. H. Moore & Company, 1851).

———. The Cruise of the Alabama and the Sumter: From the Private Journals and Other Papers of Commander R. Semmes C.S.N. and Other Officers, 2 vols. (New York: Carleton Publisher, 1864).

———. Memoirs of Service Afloat, During the War Between the States (Baltimore, MD: Kelly Piet & Co. 1869).

Sinclair, Arthur. Two Years on the Alabama (Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1895).

Spencer, Warren F. Raphael Semmes: The Philosophical Mariner (Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 1997).

Spencer, Warren F. Raphael Semmes: The Philosophical Mariner (Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 1997).

Summersell, Charles Grayson. CSS Alabama: Builder, Captain, and Plans (Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 1985).

Summersell, Charles G., ed. The Journal of George Townley Fullam: Boarding Officer of the Confederate Sea Raider Alabama (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1973).

Taylor, John M. Confederate Raider: Raphael Semmes of the Alabama (McLean, VA: Brassey’s, 1994).

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

Semmes’s invaluable journals from the Alabama and Sumter were published in The Official Records.

United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series 1, volume 1, pp. 691-744, 783-817; volume 2, pp. 720-807; and volume 3, pp. 669-77. MMost of Semmes’s unpublished papers are in the collection of Semmes Family Papers.

Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery.