The Battle of Cedar Creek

by Jack H. Lepa

The Battle of Cedar Creek was the culmination of Sheridan's 1864 Valley Campaign

Marching and fighting in the Shenandoah Valley since early August of 1864 the Union army commanded by Major General Philip H. Sheridan deserved a rest and by October 10 they began camping along the peaceful banks of Cedar Creek, about twenty miles southwest of Winchester. Sheridan’s army contained over 30,000 men in three infantry and one cavalry corps. The VI Corps under Major General Horatio G. Wright had divisions commanded by Brigadier Generals Frank Wheaton, George W. Getty, and James B. Rickets; the VIII Corps commanded by Brigadier General George Crook had divisions under Colonels Joseph Thoburn and Rutherford B. Hayes and the XIX Corps commanded by Major General William Emory with divisions led by Brigadier Generals James McMillan and Cuvier Grover. The cavalry corps commanded by Major General Alfred Torbert contained divisions led by Brigadier Generals Wesley Merritt, George A. Custer and Colonel William H. Powell. 1

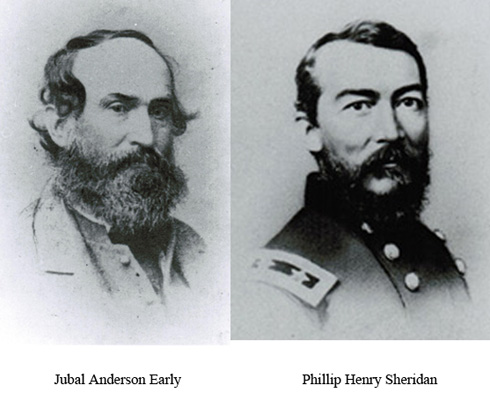

Located between the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains the Shenandoah Valley begins near Lexington and runs northeast approaching Maryland. Controlling the Valley was essential for success in Virginia since forces sent through the mountain gaps could deliver a devastating flank attack on the main armies to the east. Also, a Rebel army emerging from the northern end of the Valley was in position to threaten Pennsylvania or Washington D.C. But most important of all was the land itself, some of the most fertile soil on the continent that consistently produced large wheat and corn harvests and superior livestock. There was a reason the Shenandoah Valley was frequently called “the Breadbasket of the Confederacy.” Sheridan’s assignment was to rid the Valley of Confederate forces and destroy everything that could aid the Southern war effort. Following victories over Lt. General Jubal A. Early’s Confederate forces at Winchester and Fisher’s Hill, Sheridan’s army began methodically destroying barns, mills, and food supplies. Writing to General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant, Sheridan promised that when finished, “the Valley, from Winchester up to Staunton, ninety-two miles, will have but little in it for man or beast.” (2)

On October 14th Sheridan was summoned to Washington for a conference on future operations. On the return trip he arrived at Winchester on the evening of the 18th where a message was received from General Wright, in charge of the army while Sheridan was gone, that all was quiet and a reconnaissance was being sent out in the morning. Sheridan went to bed planning to make a leisurely ride back to the army on the 19th. 3

In the Confederate camp at Fisher’s Hill, Jubal Early had about 16,000 men. The army had five infantry divisions commanded by Major Generals John B. Gordon, Joseph B. Kershaw, Stephen D. Ramseur and Brigadier Generals John Pegram and Gabriel Wharton. There were two cavalry divisions commanded by Major Generals Thomas L. Rosser and Lunsford Lomax. Little food was available in the area so Early either had to fall back or move forward. Not strong enough to make a frontal assault on the Union camp, Early, “determined to get around one of the enemy’s flanks and attack him by surprise….” General Gordon and topographical engineer, Captain Jed Hotchkiss climbed to the signal station on Massanutten Mountain to examine the Federal position while General Pegram inspected the Federal right. 4

From his vantage point Gordon had a clear view of the Federal camps, “every parapet where his heavy guns were mounted, and every piece of artillery, every wagon and tent and supporting line of troops, were in easy range of our vision.” The right side of the Union position looked too strong for a successful assault, however, the Federal left, protected by the mountain was weakly fortified. 5

Gordon saw that, “it required, therefore, no transcendent military genius to decide quickly and unequivocally upon the movement which the conditions invited.” The opportunity for a stunning victory was there for the taking and if Early adopted his plan of battle, “the destruction of Sheridan’s army was inevitable.” Hotchkiss returned to headquarters with a sketch of the Federal camps and information on a difficult but useable route around the mountain to the Union left. 6

Gordon reported his findings to Early and when Pegram confirmed the strength of the Federal right it was clear that an attack on the left was the only viable opportunity. A daring plan was developed and Early ordered the army to move that night. General Gordon would lead three divisions, his, Ramseur’s and Pegram’s, around the mountain. Launching a surprise attack on the Union left Gordon was to push west toward the Valley Pike. At the same time Kershaw’s division would attack the front line of the Federal left along the creek. Wharton was to press up the pike with the artillery while Rosser engaged the Federal cavalry on their right. 7

As Gordon’s men moved through the night, “the long gray line like a great serpent glided noiselessly along the dim pathway above the precipice.” The journey over the rugged trail was difficult enough but then they had to wait for nearly an hour while Federal pickets patrolled nearby. When Kershaw and Wharton moved out they followed the pike to Strasburg where Kershaw moved to the right and Wharton followed the road to Hupp’s Hill, where he was to wait for the artillery. Early stayed with Kershaw and about 3:30 a.m. they came within sight of the Federal campfires. 8

Along Cedar Creek the Union troops passed a beautiful fall day in the Shenandoah Valley. Many in the Union camp were convinced that Early’s army was beaten and no longer a serious threat. A reconnaissance during the day found no enemy in the vicinity. General Wright wrote that “we had been expecting for some days that he would either attack us or be compelled to fall back for the supplies.” But just to be sure, he ordered another reconnaissance to be sent out early on the 19th. 9

That evening, the Union soldiers gathered around the campfires to argue about the coming election and read letters from home until taps was sounded. Colonel A. B. Nettleton of the 2nd Ohio Cavalry remembered that by midnight all that could be heard in the camp was the tramp of the guards and, “all was tranquil as a peace convention” as the men slept. 10

It began about 4:30 a.m. There was just a faint bit of light as Brigadier General Clement Evans led the Confederates across the creek. Gordon’s men “did not hesitate for a moment.” Cold and wet they quickly reached the left flank of Crook’s sleeping men, hitting them like lightning out of a clear sky. Colonel Hayes’ 2nd Division was on the end of the Federal line, at right angles with Colonel Thoburn’s 1st Division facing Cedar Creek. They were overwhelmed in a matter of minutes. Gordon later wrote that the few men who were awake and able to make some kind of stand “were thrown into the wildest confusion and terror by Kershaw’s simultaneous assault in front.” 11

Kershaw’s troops came out of the early morning fog and swarmed over Thoburn’s half-dressed troops. To Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Wildes of the 116th Ohio Infantry it seemed that the enemy was coming from every direction. Wildes reported that he had just formed his men “when I heard firing in the woods immediately in my rear.” Colonel Thoburn was killed as the stunned Union soldiers tried to put up a fight but were quickly overwhelmed and soon most were running for their lives. Hundreds of Union soldiers were captured and many were shot down as they attempted to escape. 12

Colonel T. M. Harris took over command of the 1st Division after Thoburn was killed, but there was nothing he could do to stop or even slow the Confederate tide. The 1st and 3rd Brigades were split by the attackers and hit by heavy fire from the front and flanks. Colonel Harris reported that “these two brigades were driven from the works, and so heavy and impetuous was the enemy’s advance that their retreat was soon, for the most part, converted into a confused rout.” The VIII Corps virtually ceased to exist as a fighting unit. The men who were able to flee headed for the rear past the XIX Corps with the triumphant Confederates right behind them. 13

The VIII Corps collapsed so quickly that General Emory’s XIX Corps had little time to prepare to meet the assault. In the darkness and fog they could not tell where the firing was coming from, but it was getting closer. Staff officer Captain John W. Deforest wrote that, “through the unmanned gaps in the lines poured the Rebels in a roaring torrent.” It was just enough light to see how near the army was to disaster when Emory ordered Colonel Stephen Thomas to block the advancing Confederates with the 2nd Brigade of the 1st Division: “It was a fearful necessity that required a detachment to be sent to almost instant destruction, in order to gain time.” 14

General Wharton’s men were also hitting the XIX Corps front but faced stubborn resistance on their front line. With Gordon’s men coming in from the left and rear, Early directed Wharton to press his assault more vigorously and brought up artillery for support. Desperate to hold his position, General Emory moved some of his men to the reverse side of their breastworks. A soldier in the 159th New York remembered that his regiment “was formed in line in front of the rifle pits to oppose the attack in the rear; but it was impossible to resist the rush of the rebels.” Kershaw’s troops were now joining Gordon’s men on the left and Emory had to pull his men back before they were trapped between the two enemy forces. 15

The fate of the army now rested on the VI Corps under General Rickets who replaced General Wright. Farthest from the initial attacks they had little idea what was happening until the nearby fields began to fill with stragglers. Colonel Warren Keifer, who took over Rickets command, saw so many retreating soldiers, “that for a time the lines had to be opened at intervals in order to allow them to pass to the rear.” Surgeon George T. Stevens of the 77th New York later wrote, “…the truth flashed upon us. More than half of our army was already beaten and routed.” 16

General Ricketts was wounded early in the fighting and command of the corps fell to General Getty. Wright ordered the VI Corps to fall back to cover the left and they formed up with the 2nd Division near the pike and the 1st and 3rd Divisions to the right. There was little time to form a solid defensive line and the three divisions had to face the oncoming Confederates separately. 17

Kershaw’s troops struck the 3rd Division at about the same time Gordon’s men attacked General Wheaton’s 1st Division to the north. Both divisions held their ground for a brief time, but as earlier the Confederates were able to flank the Union positions and come in from the rear and soon both divisions were forced to fall back. 18

Now only the 2nd Division was left to carry on the fight. With two of his three divisions falling back General Getty stayed with these troops and pulled them back about 300 yards to the crest of a hill. There was no support on the right of the division, but on the left Brigadier General Daniel Bidwell’s brigade was loosely connected with Federal cavalry. 19

Soon after Getty had established this latest line, they were attacked. Colonel Thomas Hyde of the 1st Maine reported that fog and smoke made it difficult to see more than a short distance “when suddenly the enemy appeared in two lines, within thirty yards of our line of battle.” Both lines fired almost simultaneously and the Confederates fell back. Colonel Hyde remembered, “We had scarcely reformed on the hill when the enemy appeared again on the crest within thirty yards of our lines, and, as before, we poured a heavy volley into them, charging, when they fled in the wildest confusion.” During this action General Bidwell was mortally wounded by a shell. 20

For over an hour the 2nd Division stubbornly held its ground against multiple Confederate attacks, both Gordon and Early believed they were facing the entire VI Corps and not just one division. With victory almost achieved Gordon recognized that, “Only the Sixth Corps of Sheridan’s entire force held its ground. It stood like a granite breakwater, built to beat back the oncoming flood.” 21

Realizing how strong Getty’s position was Gordon was determined to remove this last obstacle to a complete victory: “I had directed every Confederate command then subject to my orders to assail it in front and upon both flanks simultaneously.” Gordon was making arrangements to begin an artillery bombardment of the 2nd Division’s position when General Early arrived on the scene. 2

General Gordon never forgot the brief conversation that took place. Early said, “Well Gordon, this is glory enough for one day. This is the 19th. Precisely one month ago to-day we were going in the opposite direction.” Gordon replied, “It is very well so far, general; but we have one more blow to strike, and then there will not be left an organized company of infantry in Sheridan’s army.” Gordon informed Early of steps he was taking to destroy the remaining Union force but Early said, “No use in that; they will all go directly.” Gordon protested, “That is the Sixth Corps, general. It will not go, unless we drive it from the field,” to which Early replied, “Yes, it will go too, directly.” Gordon remembered that, “my heart went into my boots,” as he had to settle for an artillery bombardment of the Union position. 23

Although the Confederate shelling caused few casualties Getty decided to pull the division back to a new position about one mile north of Middletown with the left resting on the Valley Pike and cavalry on the right. Gordon had gotten what he wanted but the situation was now totally changed. For the first time that day a Confederate assault had been stopped cold. The 2nd Division occupied a good defensive position and Getty sent out orders for the rest of the VI Corps to regroup at his new location. 24

During the early morning fighting most of the Federal cavalry was protecting the right flank. When Rosser’s troopers moved forward they ran into strong resistance. Colonel James Kidd, commanding Merritt’s 1st Brigade, moved forward to support the picket line and was soon reinforced by Colonel Charles Russell Lowell’s brigade. The heavy Federal cavalry presence forced Rosser to remain on the opposite side of the creek throwing a few shells toward the Union troopers. Brigadier General Thomas C. Devin’s 2nd Brigade was ordered to the left to protect the pike and try to stem the flow of refugees. 25

When the new lines were being set up north of Middletown, General Wright ordered the cavalry to move over to the left of the lines, with Merritt’s 1st Division north of Middletown across the pike, Custer’s 3rd Division to their left and the 1st Brigade of Colonel Powell’s 2nd Division on Custer’s left. The 2nd Brigade of the 2nd Division was confronting General Lomax’s Confederate cavalry where they spent most of the day protecting the supply trains and the Federal rear. About 11:00 o’clock Custer’s division was sent back to the right of the infantry lines where he was “almost in rear and overlooking the ground upon which the enemy had massed his command.” Early was now faced with one of his greatest concerns, Federal cavalry divisions on both his flanks. 26

When it came time to attack the new Federal position Ramseur and Kershaw were ready but Gordon’s troops were still coming up. By the time all was ready Early learned of Custer’s cavalry on his left. Knowing what a cavalry attack on the flank could do to attacking troops, he directed Gordon not to make the assault if the Federal line was too strong. Gordon sent skirmishers forward but they soon returned to report the Federal line was indeed strong. The main attack was canceled. Gordon wanted to continue the assault regardless of what the Federal cavalry might do but he was forced to wait “till the routed men in blue found that no foe was pursuing them and until they had time to recover their normal composure and courage….” 27

Early finally decided to, “hold what had been gained, and orders were given for carrying off the captured and abandoned artillery, small arms and wagons.” His troops were exhausted and most units were scattered and under strength from losses and men absent while looting the Federal camps. The Federal army was growing in strength and their cavalry was now threatening both flanks. Early could have left the field with a spectacular victory intact. Instead he simply held his ground and waited. Major Henry K. Douglas, one of his staff, remembered that Early later commented, “The Yankees got whipped; we got scared.” 28

While the Army of the Shenandoah was being battered, its commander was still in Winchester. Sheridan was twice informed that artillery firing could be heard coming from the direction of Cedar Creek. He believed it was due to the reconnaissance taking place that morning but after the second report he decided to hurry up breakfast and head back to the army earlier than planned. 29

About 9 a.m. as Sheridan and his aides rode south faint but sustained artillery fire could be heard in the distance. One of the general’s aides, Major George Forsyth recalled, “He leaned forward and listened intently, and once he dismounted and placed his ear near the ground, seeming somewhat disconcerted as he rose again and remounted.” Not far out of Winchester they came upon a wagon train in total chaos with wagons facing every direction. The quartermaster in charge said he had been told that the army was defeated and he should head back to Winchester. 30

Sheridan’s first thought was to rally the troops and set up new lines outside of Winchester. But as he gained more information he changed his mind. Confident that the troops trusted in him and that they would rally to him Sheridan decided “I ought to try now to restore their broken ranks, or, failing in that, to share their fate because of what they had done hitherto.” 31

Along the Valley Pike small groups of soldiers were scattered across the fields and Sheridan began riding out among them waving his hat and calling to the men to follow him. Forsyth noted that “one glance at the eager face and familiar black horse and they knew him, and starting to their feet, they swung their caps around their heads and broke into cheers as he passed beyond them.” More importantly most of them followed Sheridan back toward the battlefield. 32

Mile after mile Sheridan rode on his large, black charger named Rienzi, stopping occasionally to ask for news. A legend grew that Rienzi galloped the entire way from Winchester to the battlefield without a stop. For once the truth is very close to the legend: a large black horse, white with foam and charging toward the battle, the small dark man waving his hat and yelling at the men as he went by urging them to follow him. 33

On the VI Corps line the waiting men were not too happy about the situation. Aldace F. Walker, of the Vermont Brigade, remembered that as the army was re-forming they were, “sulkily and it is to be feared profanely growling over the defeat in detail which we had experienced….” Then, suddenly, “we heard cheers behind us on the pike. We were astounded.” They had been driven four miles and had been on the edge of disaster when far to the rear they began to hear the “stragglers and hospital bummers, and the gunless artillerymen actually cheering as though a victory had been won. We could hardly believe our ears.” 34

Sheridan found Wright, who had been slightly wounded on the chin, sitting on the grass, exhausted, with his beard covered in blood. He apologized saying, “Well we’ve done the best we could.” But Sheridan kindly responded, “That’s all right; that’s all right.” Wright had already taken steps to combine the remaining troops into a continuous line. Sheridan approved his dispositions deciding to launch his assault as soon as preparations were complete. 35

It took time but as the stragglers returned to their units the new line of battle gradually took shape. Major Forsyth noted that as the tired and dirty men came up, “Little was said by officers or men, for the truth was nearly all were tired, troubled, and somewhat disheartened by the disaster that had so unexpectedly overtaken them….” Knowing what it took to return to the fight Sheridan wrote in his report, “none behaved more gallantly or exhibited greater courage than those who returned from the rear determined to reoccupy their lost camp.” 36

When the army was formed to Sheridan’s satisfaction, the VI Corps’ line had the 2nd Division on the left, the 1st in the center, and the 3rd on the right. As the men from the XIX Corps returned they formed on the right and behind the VI Corps. Custer’s cavalry stayed on the right and Merritt on the left. As the formations grew Sheridan rode along the line to show the men that he had returned and was again in command. He promised the cheering soldiers that, “…now we are going back to our camps. We are going to get a twist on them. We are going to lick them out of their boots.” 37

It was well after three o’clock by the time Sheridan was ready to launch his attack. The plan was to advance “in a swinging movement, so as to gain the Valley pike with my right between Middletown and the Belle Grove House….” As word of the coming assault spread the men rose from their resting spots forming their ranks and prepared for what lie ahead, quietly leaning on their rifles and grimly gazing toward the enemy. 38

About a mile from the Union lines the Confederates were also waiting, and they knew what was coming. After the early morning fighting the Confederates were drawn up across the Valley Pike a little north of Middletown with Gordon’s divisions now on the left. Pegram and Wharton were on the right near the pike, which they had to protect at all costs. There was a lightly guarded break in the lines on Gordon’s right that the Confederate commanders were unable to fill in time. 39

The Federal line moved forward a little before four o’clock. Getty’s division advanced with their left along the pike with Wheaton and Kiefer to the right. The XIX Corps was further to the right and moving at an angle swinging toward the pike. As the VI Corps advanced they ran into a hail of enemy bullets. Ramseur and Kershaw held their ground tenaciously, pouring fire into the Union ranks from behind hastily erected barricades. The Union line came to a halt and began trading fire. Colonel Keifer’s division, “lost very heavily in this attack.” In the 2nd Division, Colonel Hyde, whose 3rd Brigade was along the pike, reported advancing about 250 yards, “when the enemy opened on us with canister from a battery behind the mill, and an infantry fire from a line posted behind a stone wall in our front and right.” 40

It took nearly an hour of brutal fighting with heavy casualties on both sides before the sheer weight of the VI Corps’ attack forced Ramseur and Kershaw back towards Middletown. General Ramseur rallied his men behind a stone fence about 200 yards in the rear but while trying to hold this position he was mortally wounded. 41

While the VI Corps was heavily engaged on the left, the XIX Corps was also meeting desperate resistance on the right. Emory’s 1st Division was on the right of his corps and their job was to swing around the flank of Gordon’s men and drive them toward the center. Moving forward they ran into a storm of bullets from the Confederates behind a low walls of fence rails and stones. Emory’s men traded fire with the Confederates until suddenly they began receiving fire from their right. Fortunately, General McMillan was able to position a brigade to confront this threat and after a brief but terrible fight Gordon’s men were forced back. 42

Over on the Federal right General Custer was watching the infantry battle from a ridge when he saw that, “it was apparent that the wavering in the ranks of the enemy betokened a retreat, and that this retreat might be converted into a rout.” With the exception of three regiments confronting Rosser’s cavalry Custer led his division forward. 43

As Custer’s troopers moved across the open fields they could be seen from the XIX Corps lines. General McMillan ordered his men forward and they drove the enemy back until Federal infantry came up on the far left and rear of the Confederate line where they poured fire into their exposed flank. Gordon’s men bravely resisted at first but soon the left of the line broke for the rear. 44

General Gordon was conferring with Early when the attack began and hurried to the front to find his troops, “almost completely surrounded by literally overwhelming numbers….” Gordon watched the Federal infantry “assailing our main line on the flank and rolling it up like a scroll. Regiment and regiment, brigade after brigade, in rapid succession was crushed….” 45

As the two divisions of the XIX Corps were pushing Gordon’s men back, Custer’s cavalry could clearly be seen moving around the Confederate flank. Custer reported, “Seeing so large a force of cavalry bearing rapidly down upon an unprotected flank and their line of retreat in danger of being intercepted, the lines of the enemy, already broken, now gave way in the utmost confusion.” 46

Over on the VI Corps front the battle was also nearing its climax. With intensified fighting all across the battlefield Pegram and Wharton had to protect the line of retreat down the Valley Pike and could spare no troops to reinforce the failing left. Finally Early had to concede, “every effort to rally the men in the rear having failed, I had now nothing left for me but to order these troops to retire also.” 47

Merritt timed his last charge perfectly as he and Custer swept around both flanks of the retreating Confederates. Even Gordon knew it was the end, recalling that, “as the tumult of battle died away, there came from the north side of the plain a dull, heavy swelling sound like the roaring of a distant cyclone, the omen of additional disaster.” The sound was unmistakable, Union cavalrymen riding across the open fields to intercept the Confederates before they could get away. Gordon now realized that “the only possibility of saving the rear regiments was in unrestrained flight – every man for himself.” On the right the Confederates also broke for the rear, “the stampede on the left was caught up, and no threats nor entreaties could arrest their flight.” 48

New Yorker George Stevens remembered that, “our men, with wild enthusiasm, with shouts and cheers, regardless of order or formation, joined in the hot pursuit.” Pursuing the fleeing Confederates, Custer noted what had been “a pursuit after a broken and routed army now resolved itself into an exciting chase after a panic-stricken, uncontrollable mob. It was simply a question of speed between pursuers and pursued….” 49

Darkness ended the chase and slowly the victorious Federal troops returned to the camps they abandoned that morning, Sheridan had kept his promise. While sitting around the fire that night Sheridan admitted to General Crook, “I am going to get much more credit for this than I deserve, for, had I been here in the morning the same thing would have taken place, and had I not returned today, the same thing would have taken place.” 50

Sheridan’s army lost 644 killed, 3,430 wounded and 1,591 missing for total casualties of 5,665. A member of Early’s staff reported his casualties at 1,860 killed and wounded and Sheridan reported capturing about 1,600 Confederates. It was an expensive victory but worth the terrible price. The surviving Confederates were devastated, not just from the loss of men and equipment, but their morale was shattered beyond repair. 51

That night Sheridan wired Grant a preliminary report of the battle explaining the early morning defeat and telling how he rallied the men and attacked, but giving most of the credit for the victory to his troops, concluding that, “affairs at times looked badly, but by the gallantry of our brave officers and men disaster has been converted into a splendid victory.” 52

Early fell back to Fisher’s Hill then to New Market. Explaining to General Lee how a brilliant victory turned into a demoralizing defeat Early basically blamed the men who left the ranks to loot and complained that “my left gave way, and the rest of the troops took a panic and could not be rallied, retreating in confusion. But for their bad conduct I should have defeated Sheridan’s whole force….” The next day Early published a long and mostly critical message to his army singling out the men who, “yielded to a disgraceful propensity for plunder,” for deserting their comrades who, “yielded to a needless panic and fled the field in confusion, thereby converting a splendid victory into a disaster.” 53

At the end of October, Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana made a tour of the Shenandoah Valley reporting that “the devastation of the Valley, extending as it does for a distance of about one hundred miles, renders it almost impossible that either the Confederates or our own forces should make a new campaign in that territory….” Philip Sheridan’s mission was completed. 54

1. United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A

Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: United States War Department, 1880-1901, Vol. 43, Part 1, 125-130. Philip H. Sheridan, Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan. Vol. 2, New York: Charles L. Webster & Co., 1888, 68-79.

2. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 31.

3. Sheridan, Vol. 2, 60, 66-68.

4. Jubal A. Early, A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence in the Confederate States of America. New Orleans: Blelock & Co., 1867, 83.

5. John B. Gordon, Reminiscences of the Civil War. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903, 333-334.

6. Gordon, 335. Early, Last Year of the War. 83-84.

7. Early, Last Year of the War, 83-85. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 580.

8. Gordon, 336-37. Early, Last Year of the War, 86.

9. A. B. Nettleton, “The Famous Fight at Cedar Creek,” The Annals of the Civil War, Ed. Alexander Kelly McClure. New York: De Capo Press, 1994, 658. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 158.

10. Nettleton, 659.

11. Gordon, 339. Official Records, Vol. 43. Part 1, 365.

12. Augustus D. Dickert, History of Kershaw’s Brigade. Dayton, Ohio: Morningside Bookshop, 1973, 447-448. Gordon, 339-340. J. W. DeForest, “Sheridan’s Victory of Middletown,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. February 1865, 354. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 380. Gordon, 340.

13. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 372.

14. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 284. DeForest, 354. George N. Carpenter, History of the Eighth Regiment Vermont Volunteers 1861-1865. Boston: Press of DeLand & Barta, 1886, 209-210.

15. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 284-85. Early, Last Year of the War, 86. William F. Tiemann, compiler, The 159th Regiment, New York State Volunteers, in the War of the Rebellion. Brooklyn, NY: William F. Tiemann, 1891, 107-108.

16. George T. Stevens, Three Years in the Sixth Corps. Albany, NY: S. R. Gray, Publisher, 1866, 416. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 226.

17. Stevens, 418. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 158-159.

18. DeForest, 357. Stevens, 420-421.

19. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 193-194.

20. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 215.

21. Gordon, 340.

22. Gordon, 341.

23. Gordon, 341.

24. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 194.

25. J. H. Kidd, Personal Recollections of a Cavalryman. Ionia, MI: Sentinel Printing Co., 1908, 411. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 449, 433.

26. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 433-434, 449, 523.

27. Early, Last Year of the War, 89. Gordon, 344.

28. Early, Last Year of the War, 89-90. Henry Kyd Douglas, I Rode with Stonewall. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1940, 319.

29. Sheridan, Vol. 2, 68-71.

30. George A. Forsyth, “Sheridan’s Ride,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, July 1897, 168. Sheridan, Vol. 2, 80.

31. Sheridan, Vol. 2, 78-79.

32. Forsyth, 170-171.

33. Richard O’Connor, Sheridan the Inevitable. New York: Konecky & Konecky, 1993, 226. Bruce Catton, Bruce Catton’s Civil War. New York: The Fairfax Press, 1984, 643.

34. Aldace F. Walker, The Vermont Brigade in the Shenandoah Valley 1864. Burlington, VT: The Free Press Association, 1869, 146-147.

35. E. R. Hagemann, Ed., Fighting Rebels and Redskins: Experienced in Army Life of Colonel George B. Sanford 1861-1892. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969, 291. Sheridan, Vol. 2, 83-84. Stevens, 422.

36. Forsyth, 176. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 54.

37. Hagemann, 291. Sheridan, Vol. 2, 83-84. Stevens, 422. DeForest, 358.

38. Sheridan, Vol. 2, 88. Forsyth, 177-178.

39. Gordon, 346-47. Early, Last Year of the War, 90.

40. Stevens, 424-25. Deforest, 359. Sheridan, Vol. 2, 88. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 227-228, 216.

41. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 195, 600.

42. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 285. Forsyth, 178-179. Sheridan, Vol. 2, 88.

43. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 524.

44. Forsyth, 179.

45. Gordon, 348.

46. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 524.

47. Early, Last Year of the War, 90.

48. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 600. Gordon, 348-349.

49. Stevens, 425, Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 525.

50. Martin F. Schmitt, Ed. General George Crook: His Autobiography. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986, 134.

51. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 137, 33. Douglas, 319.

52. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 32-33.

53. Official Records, Vol. 43, Part 1, 560. Jubal Early, “Gen’l Early’s Address to His Army,” The Staunton Vindicator, October 28, 1864, Page 2, Col. 3.

54. John Y. Simon, Ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. Vol. 12 Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1982, 365.

If you can read only one book:

Thomas A. Lewis, The Guns of Cedar Creek. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

Books:

John B. Gordon, Reminiscences of the Civil War. Charles Scribner's Sons: New York, 1903. Pg. 327-372.

J. H. Kidd, Personal Recollections of a Cavalryman. Sentinel Printing Company: Iona Michigan, 1908. Pg. 403-433.

George E. Pond, The Shenandoah Valley in 1864. Charles Scribner's Sons: New York, 1886. Pg. 220-242.

Philip H. Sheridan, Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan. Charles L. Webster: New York, 1888. Vol.2.Pg. 53-96.

Jubal A. Early, Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early: Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War Between the States. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1912. Pg. 437-452.

George T. Stevens, Three Years in the Sixth Corps. S.R. Gray: Albany New York, 1866. Pg. 414-428.

Jeffry D. Wert, From Winchester to Cedar Creek: The Shenandoah Campaign of 1864. Carlisle, Pennsylvania: South Mountain Press, 1987.

Aldace F. Walker, The Vermont Brigade in the Shenandoah Valley 1864. The Free Press Association: Burlington, Vermont, 1869. Pg. 130-161.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

The Civil War in the Shenandoah Valley. This website provides a summary of a study of Civil War sites in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia authorized by Public Law 101-628 and completed in 1992.

Cedar Creek Battlefield Foundation. The Foundation’s mission is to preserve lands associated with the Battle of Cedar Creek, and to educate others about the importance of the Battle in our local and national history.

The Battle of Cedar Creek on About.com. This website gives a brief overview of the Battle of Cedar Creek.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.