The Battle of Kelly's Ford

by Daniel T. Davis

On February 5, 1863, ten days after assuming command of the Army of the Potomac, Major General Joseph Hooker issued General Orders Number 6. It outlined Hooker’s organizational plans. A critical element of the order involved the army’s mounted arm. For the first time in its existence, Hooker’s cavalry would operate in a single corps under one commander, Brigadier General George Stoneman Jr. Prior to this Union cavalry was disorganized and split up in small units among corps, division and brigade commanders. General Orders Number 6 placed Stoneman and his troopers on the same structural level as their Confederate counterparts led by Major General James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart. In early March 1863 Hooker dispatched Brigadier General William Woods Averell, commander of the Second Division of the new cavalry corps, to attack Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee who commanded three Confederate cavalry regiments in camp across the Rappahannock River near Kelly’s Ford. At 8:00 a.m. on March 17, Averell arrived opposite the ford and fighting began as the federals tried to force a crossing. By noon Averell’s whole force was across the river and began to advance on the road northwest from the river. The federal cavalry ran into Lee’s advancing cavalry and the two forces charged forward. At some point during the attack, Major John Pelham, the commander of the Stuart Horse Artillery, rode forward with the Virginians, fell mortally wounded by a round fired by the federals. Attack followed counterattack until darkness began to fall. At that point Averell decided to withdraw and return to union lines. Averell and his men returned triumphantly to their camps. He not only vindicated himself but proved the value of Hooker’s decision to reorganize the mounted arm. The Federals inflicted 133 casualties on the Confederates while only losing 78 killed, wounded, and missing. “The principal result achieved by this expedition has been that our cavalry has been brought to feel their superiority in battle; they have learned the value of discipline and the use of their arms,” Averell reported. Kelly’s Ford began the ascension of the Union cavalry. Subsequent fighting later that summer at Brandy Station, Aldie, Upperville and Gettysburg proved for the first time in the war, they were equals of Stuart and his troopers.

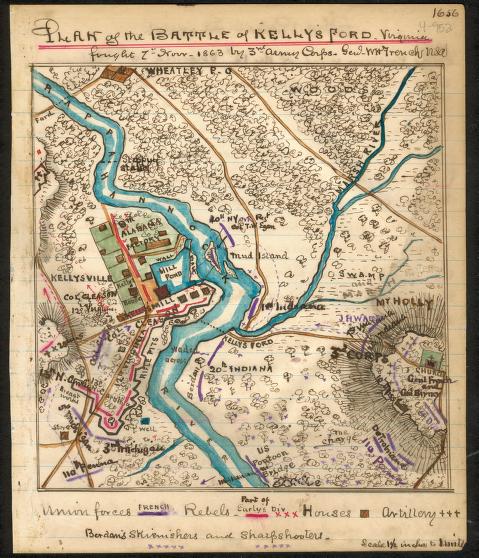

17th March 1863 Kelly’s Ford Va – Plan Showing Battle Ground and Cavalry Fight by Robert Knox Seldon 1863-1865

Map Courtesy of the Virginia Museum of History & Culture

On February 5, 1863, ten days after assuming command of the Army of the Potomac, Major General Joseph Hooker issued General Orders Number 6. It outlined Hooker’s organizational plans. A critical element of the order involved the army’s mounted arm. For the first time in its existence, Hooker’s cavalry would operate in a single corps under one commander, Brigadier General George Stoneman Jr.

Prior to Hooker’s order, the cavalry “was disorganized by furnishing details as escorts, guides, orderlies and small scouting parties” wrote Wesley Merritt, an officer in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. The cavalrymen were “divided…up….among [the] infantry corps, division and brigade commanders so that the smallest infantry organization had its company or more of mounted men, whose duty consisted in supplying details as orderlies for mounted staff officers, following them mounted on their rapid rides for pleasure or for duty, or in camp acting as grooms and boot-blacks at the various headquarters…this treatment demoralized the cavalry” recalled an incredulous Merritt.[1]

General Orders Number 6 placed Stoneman and his troopers on the same structural level as their Confederate counterparts led by Major General James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart. It remained to be seen, however, if their fighting prowess could rise to that of the Confederates. A week later, Hooker issued another order regarding his new corps. The administrative measure assigned Brigadier General William Woods Averell to command of the second division.

Averell was born on November 5, 1832, in Cameron, New York. As a young man he worked as a clerk in a drugstore. Through the work of Congressman David Rumsey, Averell entered the United States Military Academy at West Point. He graduated in 1855 and received a commission in the Regiment of Mounted Rifles. Averell served at Jefferson Barracks and the cavalry school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania before heading to the frontier. He received a wound while on operations against the Navajo and returned east to recover. Averell served as a staff officer at First Manassas. On August 23, 1861 he received the colonelcy of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry. A little over a year later he was promoted to brigadier general.

In February 1863, Hooker transferred the IX Corps, Burnside’s old command, from the army to Newport News under the command of Brigadier General William Farrar “Baldy” Smith. Confederate scouts operating on the fringes of the armies along the Rappahannock River reported the movement to General Robert E. Lee. Hoping to ascertain Hooker’s intentions and whether the detachment was the beginning of a larger movement, he ordered a reconnaissance of the Union encampment.

On February 24, Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee, the commanding general’s nephew, along with detachments from the First, Second and Third Virginia cavalry regiments crossed the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford. Lee camped that night at the hamlet of Morrisville and the next morning headed toward the Federal lines near the village of Falmouth, opposite the city of Fredericksburg.

Lee, born in Fairfax County, Virginia on November 19, 1835, graduated from West Point in 1856. He resigned his officer’s commission to serve the Confederacy several weeks after the firing on Fort Sumter. He served on General Joseph Eggleston Johnston’s staff at First Manassas before taking command of the 1st Virginia Cavalry. Lee received a promotion to brigadier general and command of a brigade of Virginia cavalry in July 1862. Like so many officers on both sides, Lee and Averell served together in the old army at the cavalry barracks in Carlisle, Pennsylvania and became fast friends.

Averell’s stint as division commander, along with the reorganized cavalry, did not get off to a strong start. Lee’s troopers collided with pickets from his former comrade’s division at Hartwood Church, northwest of Falmouth. The Confederates soon gained the upper hand, driving the Federals back nearly four miles to Berea Church. There, Lee ran into the 86th New York and 124th New York infantry regiments. Judiciously, Lee decided to break off the fight. Before he withdrew, Lee left behind a surgeon and a note for Averell.

“Dear Averell”, Lee wrote, please let this surgeon assist in taking care of my wounded. I ride a pretty fast horse, but I think yours can beat mine. I wish you’d quit shooting and get out of my State and go home. If you won’t go home, why don’t you come pay me a visit. Send me over a bag of coffee.”[2]

The episode profoundly embarrassed Averell and infuriated Hooker. “We ought to be invincible, and by God we shall be,” Hooker exclaimed in a subsequent meeting with Stoneman. “You have got to stop these disgraceful cavalry ‘surprises’. I’ll have no more of them. I give you full power over your officers to arrest, cashier, shoot—whatever you will—–only you must stop these ‘surprises’. And by God, sir, if you don’t do it, I give you fair notice, I will relieve the whole of you, and take command of the cavalry myself!”[3]

Both men were eager to settle the score with the Confederates. A couple of weeks after Hartwood Church, Hooker dispatched Averell on an expedition across the Rappahannock to attack and destroy Lee, believed to be around Culpeper Court House, west of Fredericksburg. Averell and his troopers rode out from their winter encampment.

With him were the brigades of Colonels. Alfred Napoléon Duffié and John Baillie McIntosh. Captain Marcus Albert Reno along with the 1st U.S. Cavalry and 5th U.S. Cavalry. Lieutenant George Browne Jr. and the 6th New York Independent Battery rounded out Averell’s command.

Averell camped that evening at Morrisville and sent his scouts ahead to Mount Holly Church, about a mile from Kelly’s Ford. They returned to report sighting Confederate campfires across the river. At 4 a.m. on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1863, Averell and his 2,100 troopers departed Morrisville and headed to Kelly’s Ford.

A contingent from Major. James Cary Breckinridge’s 2nd Virginia Cavalry from Lee’s brigade picketed the ford. The Virginians had placed obstructions on both sides of the river. Breckinridge posted his men in earthworks on the south bank. Company K from the 4th Virginia Cavalry under Lieutenant William Moss stood in reserve.

The Federals arrived opposite the ford at 8:00 a.m. Averell directed two squadrons from Colonel Luigi Palma di Cesnola’s 4th New York Cavalry from Duffié’s brigade to clear the obstructions and force a crossing. Di Cesnola’s men were supported by the 5th U.S. The New Yorkers made three separate attempts to take the ford, only to be driven back by Breckinridge.

After a half an hour of fighting, Major Samuel Emery Chamberlain, Averell’s chief of staff, picked twenty men and placed them under Lieutenant Simeon Brown of the 1st Rhode Island. He ordered Brown to “cross the river and not return.”[4] Chamberlain accompanied the charge and fell wounded. Despite the loss of Chamberlain, Brown’s men stormed ahead and splashed across to the south bank. The Federal troopers managed to work around Breckenridge’s flank. Running low on ammunition, Breckinridge decided to pull out before Moss could reinforce him. The remainder of the 1st Rhode Island followed to solidify the Union position.

Now in possession of the ford, Averell began the tedious task of crossing. The current was fast and the river was about four and a half feet deep. Around noon, Averell struck out from the ford. He placed the 4th Pennsylvania from McIntosh’s brigade on the left of the road leading northwest from the river. With the 4th New York on the right, the column moved out.

It was not long before the lead elements encountered Fitzhugh Lee. The morning of March 17 found Lee in Culpeper. Apprised of the fighting, Lee first marched to Brandy Station before turning down the road leading to Kelly’s Ford. Jeb Stuart arrived on the scene shortly after Lee. Approaching the Federals, Lee sent Colonel Thomas Howerton Owen’s 3rd Virginia forward. Owen’s men slammed into the Keystoners and Empire Staters, who deployed dismounted behind a stone wall perpendicular to the road.

Recognizing an opportunity, Owen sent his men around the 4th New York’s right to get between Averell and his line of retreat at Kelly’s Ford. Watching from the rear, John McIntosh sent Averell’s old regiment, the 3rd Pennsylvania, along with Colonel John Irvin Gregg’s 16th Pennsylvania to reinforce di Cesnola’s regiment. At the same time, Browne sent a section to reinforce each end of Averell’s line.

Joined by Colonel Thomas Lafayette Rosser’s 5th Virginia Cavalry, Owen launched another assault but was unable to make any headway. At some point during the attack, Major John Pelham, the commander of the Stuart Horse Artillery, rode forward with the Virginians, fell mortally wounded by a round fired from Browne’s guns. Carried from the field, he died the next day in Culpeper.

Sensing a shift in momentum, Averell sent Duffié forward with his brigade including the 1st Rhode Island along the 6th Ohio. Lee parried with the 1st, 2nd and 4th Virginia.

“Yelling and firing their pistols, the rebels came on, in good order, for square work” recalled the chaplain of the 1st Rhode Island, Frederic Denison. “The men of the First Rhode Island and Sixth Ohio sat quietly in their saddles, with drawn sabres, till the enemy had approached within a hundred yards, when the swelling order “Charge!” was given. Now came the work…the two forces came together at full speed – horse to horse – man to man – sabre to sabre. What a fight!”[5]

Supported by squadrons from the 5th U.S., Duffié soon gained the upper hand. “The Virginians…stood up well to their work” recalled the historian of the 3rd Pennsylvania, “but used their pistols rather freely. Soon after this meeting was heard the shout remembered and spoken of by so many, from the Confederates, “Draw your pistols, you Yanks, and fight like gentlemen. But as our men had established to their own satisfaction the fact that they were gentlemen, and were now anxious to fix their status as cavalrymen, they replied only with cut, point, parry and thrust.”[6]

The pressure was too much for Lee, who withdrew back to the farm of James Newby to reform. Averell also regrouped before sending Lieutenant Robert Sweatman’s squadron from the 5th U.S. forward. The rest of the Union command followed.

As the Federals approached, Lee decided to attack. He sent the1st Virginia, 3rd Virginia and 5th Virginia toward the center and right of Averell’s line, while the 2nd Virginia and 4th Virginia attacked on the left. Averell countered by shifting the 1st U.S. to support the 3rd PA and the two regiments repulsed the 1st, 3rd, and 5th Virginia.

Duffié, meanwhile, watched the 2nd Virginia and 4th Virginia move forward and ordered a charge. The 1st Rhode Island along with elements from the 5th U.S. and the 6th Ohio slammed into the Virginians, driving them back.Reno followed up with an attack of his own with the 1st U.S. and 5th U.S. and pushed the Virginians back across Carter’s Run.

By this time, darkness began to fall over the landscape. Rather risk isolating his men by spending the night on the south bank of the river, Averell judiciously decided to pull back and return to the Union lines. Averell ordered Reno and the regulars to cover the withdrawal. While covering the rest of the force, Reno’s horse was shot out from under him. The animal fell on top of him, causing a hernia and forcing him to take a leave of absence.

Before he departed, Averell left behind a note for Lee. “Dear Fitz: Here’s your coffee. How is your horse?”[7]

Averell and his men returned triumphantly to their camps. He not only vindicated himself but proved the value of Hooker’s decision to reorganize the mounted arm. The Federals inflicted 133 casualties on the Confederates while only losing 78 killed, wounded, and missing. “The principal result achieved by this expedition has been that our cavalry has been brought to feel their superiority in battle; they have learned the value of discipline and the use of their arms,” Averell reported.[8]

An officer in the 3rd Pennsylvania echoed this sentiment. “The most substantial result of this fight was the feeling of confidence in its own ability which the volunteer cavalry gained. This feeling was not confined to the regiments engaged, but was imparted to the whole of our cavalry. The espirit de corps and morale were greatly benefited,” he wrote.[9]

Kelly’s Ford began the ascension of the Union cavalry. Subsequent fighting later that summer at Brandy Station, Aldie, Upperville and Gettysburg proved that, for the first time in the war, they were the equals of Stuart and his troopers.

For his actions on March 17, 1863, Averell received a brevet to the rank of major in the Regular army. He would, however, suffer the embarrassment of being relieved of command twice, first by Hooker during the Chancellorsville Campaign and a second time two years later in the Shenandoah Valley by Major General Philip Henry Sheridan. Still, he eventually received a brevet to major general, but resigned in May 1865. Averell became a consul to British North America ( now Canada) after the war and became heavily involved in the asphalt business. Under President Grover Cleveland, Averell served as the Assistant Inspector General of Soldiers Homes.He passed away in 1900 and is buried in Bath, New York.

His old comrade Lee eventually rose to division command and was wounded at the Battle of Third Winchester. After the war, Lee farmed briefly in Stafford County, Virginia and served as governor of the stat. When the war with Spain broke out, he received a commission as major general of U.S. Volunteers, however, he never saw combat. He retired with that rank in 1901. Lee died five years after his old friend and at one time foe. He is buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

- [1] Theophilus F. Rodenbough, From Everglade to Canyon with the Second United States Cavalry: An Authentic Account of Service in Florida, Mexico, Virginia and the Indian Country, 1836-1875 (New York: D. Van Nostrand, Publisher, 1875), 283-4.

- [2] Frank W. Hess, “The First Cavalry Battle at Kelly’s Ford, Va.” National Tribune (Washington D.C.), May 29, 1890

- [3] Frank Moore, ed., Anecdotes, Poetry and Incidents of the War, North and South, 1860-1865 (New York: Printed for the Subscribers, 1866), 305.

- [4] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 25, part 2, p. 48 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 25, pt. #, 48).

- [5] Frederic Denison, Sabres and Spurs: The First Regiment Rhode Island Cavalry in the Civil War, 1861-1865 (Rhode Island: The First Rhode Island Cavalry Veteran Association, 1876), 211-2.

- [6] William Brooke Rawle, History of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry Sixtieth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers in the American Civil War, 1861-1865 (Philadelphia, PA: Franklin Printing Company, 1905), 210.

- [7] Ibid., 214.

- [8] O.R., I, 25, 50.

- [9] Rawle, History of the Third Pennsylvania, 215.

If you can read only one book:

Wittenberg, Eric J., The Union Cavalry Comes of Age: Hartwood Church to Brandy Station, 1863. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press/Potomac Books, 2003.

Books:

Blumberg, Arnold D., "Battle of Kelly's Ford, Virginia," in David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, eds. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Cooke, Jacob B., Battle of Kelly’s Ford, March 17, 1863. By Jacob B. Cooke, (Late First Lieutenant, First Rhode Island Cavalry). Providence: Soldier’s and Sailors’ Historical Society of Rhode Island, 1887.

Maxwell, Jerry H., The Perfect Lion: The Life and Death of Confederate Artillerist John Pelham. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2011.

Organizations:

Kelly's Ford Interpretive Center

An interpretive center has been opened at Kelly’s Ford.

Web Resources:

This is the American Battlefield Trust page on the Battle of Kelly’s Ford.

Historian Clark B. Hall describes the Battle of Kelly’s Ford in this short video. Additional resource links are provided on this page.

The Battle of Kelly’s Ford is a website that provides a repository of resources on the battle.

This is the Emerging Civil War’s essay on Kelly’s Ford written by Daniel Davis.

Other Sources:

FROM THE RAPPAHANNOCK; The Late Brilliant Affair at Kelly's Ford. The First Real Cavalry Fight of the War. The Rebels Driven Six Miles Beyond the River. Gallant Charges and Hand-to-Hand Conflicts. The Effectiveness of the Sabre Tested. OUR CASUALTIES LESS THAN FORTY. A large Number of Rebels Killed and Wounded and Sixty Taken Prisoners.

This New York Times article on the Battle of Kelly’s Ford was published on March 20, 1863.

Kelly’s Ford: The Most Important River Crossing of the Civil War

This essay on Kelly’s Ford, written by Clark B. Hall.

Kelly’s Ford Interpretive Center

The Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park is operated by the National Park Service and includes Kelly’s Ford. The park is open from sunrise to sunset seven days a week all year. It is located at 20 Chatham Ln

Fredericksburg, VA 22405. (540) 693-3200.The Battle of Kelly’s Ford, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park

This is the park’s page on the battle which includes directions to the battlefield and a self-guided tour.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper Volume 16 1883

The complete issues of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper from 1860-1865 is available on DVD for $12.50.