The Battle of Rich Mountain

by Charles P. Poland, Jr.

In May 1861 Federal forces under Major General George B. McClellan invaded western Virginia to protect the B&O Railroad, a vital rail link between the Midwest and East. After a small Confederate force under Colonel George Porterfield was defeated at Philippi, Confederate authorities sent a force of 4,000 men under Brigadier General Robert Garnett to block the Federals advancing from Philippi and to attempt to cut the B&O. Garnett placed a force of 800 men under Colonel John Pegram blocking the pass at Rich Mountain to the south, 2,800 under his command blocking the pass at Laurel Hill twenty-three miles to the north and 400 men at his base of supply in the town of Beverly in the valley behind the passes. McClellan sent a 4,000-man force under Brigadier General Thomas Morris to pin Garnett at Laurel Hill while he led a 7,000-man force to attack Pegram at Rich Mountain. Morris and Garnett sparred ineffectively from July 7 to July 11. McClellan reached Rich Mountain on July 10 and deciding a frontal assault would be too costly, sent a force under Brigadier General William S. Rosecrans, guided by a local unionist sympathizer on a route through the mountains around the Confederate left. Simultaneous attacks by McClellan in front of Pegram’s Confederates and Rosecrans in their rear were planned. On the afternoon of July 11 Rosecrans attacked. Hearing cheering from Pegram’s Confederates, McClellan did not attack as planned. Rosecrans pressed his attack successfully, but with darkness and not understanding the degree of his success, he did not pursue the Confederates. Pegram’s men scattered during the night and the next morning Rosecrans captured the sick and wounded Confederates left behind at Rich Mountain. Learning of the defeat of Pegram at Rich Mountain, Garnett ordered a rearguard on the road between Rich Mountain and Beverly and began to retreat. By midday July 12 McClellan crossed Rich Mountain and occupied Beverly then moved south through Cheat Mountain to Huttonsville. Mistaking retreating Confederates for advancing Federals, Garnett chose to retreat north east through difficult terrain rather than south through Beverly and Cheat Mountain. The retreat in bad weather and on poor roads turned into a disaster with sick, hungry men separated or left behind. Finally, on July 19 the remnants of Garnett’s command reached Monterey with stragglers arriving over the next week. The victory at Rich Mountain led to the creation of the state of West Virginia and the elevation of George McClellan to general-in-chief of all Union forces.

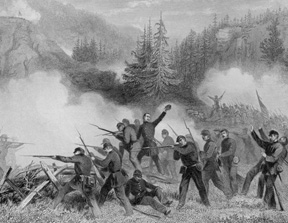

1864 Steel Engraving of the painting Battle of Rich Mountain by Alonzo Chappel.

Picture courtesy of: US Army Center for Military History Army Art Collection.

Virginia, like the nation in 1861, was sharply divided over slavery and the preservation of the union. Both were divided by divisions that originated from geographic differences that led to conflicting economic interests. The Allegheny Mountains cut diagonally across the Old Dominion, separating the two Virginias. Most of the commonwealth’s whites and almost all of the half-million slaves lived east of the Alleghenies in what would become present-day Virginia. The trans-Allegheny region comprised about one-third of the state’s territory and would make up most of what would become West Virginia. Much of what would become West Virginia had an economy that was more closely tied to that of the Ohio Valley and the North rather than to the neighbors to the east and south. This led to strong Unionist sentiment in western Virginia (twice that for the Confederacy) and difficulties for Confederate recruitment.

The Alleghenies not only divided Virginia but also served as a barrier against Union penetration into the Shenandoah Valley. As the war progressed, Union forays across the gaps in the mountains and movements up and down the seams created by the narrow valleys between numerous mountain ridges in the Allegheny chain would increasingly threaten eastern Virginia’s breadbasket, the Shenandoah Valley, also known as the Great Valley.

What caused the first Federal invasion in western Virginia was the security of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (the B&O), a vital rail link between the Midwest and East. Well aware of its important logistical role, Southerners attempted to cut this rail link used by the Union. Under the command of a young ambitious officer, Major General George Brinton McClellan, Ohio volunteers joined Unionist volunteers from the western regions of the Old Dominion in late May 1861. By the end of July 1861, the Federals were in control of Virginia west of the Allegheny Mountains. This had been achieved by thwarting Confederate plans to capture the town of Grafton, chasing southward a Southern force of 600 ill-equipped men under Colonel George Alexander Porterfield from Philippi and an even larger Southern force further south in the Rich Mountain campaign.

McClellan’s Plan

Southern authorities hoped the promising young brigadier general with fine credentials, Robert Selden Garnett, with additional troops could do what Porterfield could not. Garnett arrived at Huttonsville on June 14, 1861. He moved his command northward to block the approaching Federals. Part of his force was positioned at the western base of Rich Mountain, on the Parkersburg Turnpike, seven miles west of Beverly. Garnett and the rest of the men went more than twenty miles further north, where they took possession of Laurel Hill on June 16. The two entrenched Confederate camps were located on two vital turnpikes that led to Stanton and were on the most westerly range of the Alleghenies of the Appalachian system. Garnett strategically positioned his 4,000 men in an area that has been called the “gates to southwest Virginia.” He placed a fifth of his men under Lieutenant Colonel John Pegram at Rich Mountain, placed nearly 400 at Beverly, which became his supply base, and placed the remainder of his men, the bulk of his command, at Camp Laurel, two miles south of Belington.

The topographical features of the mountains in the region of the Confederate camps formed the shape of a gigantic yawning worm. Rich Mountain formed the belly, in the middle of which was Pegram at Camp Garnett. To the north, at the opening of the mouth, was Garnett at Laurel Hill. To the east of Laurel Mountain, at the top of the head of the configuration, was Valley Mountain. The back was formed by Cheat Mountain. It curved southward forming the eastern boundary of the approximately two-mile wide, long valley. The valley was traversed north-south by a turnpike and the Tygart Valley River. On the turnpike that cut southward through the middle of the valley were three towns: in the north, Leadsville (modern-day Elkins), in the center, Beverly, and to the south, Huttonsville. This made Beverly the logical place for storing Confederate supplies from Stanton. From the Beverly depot, they could be moved westward to Pegram and northward to Garnett.

Garnett, as urged by General Robert E. Lee, hoped to do more than guard the two passes. He wanted to destroy the B&O Railroad, but lacked the manpower to take it. He proposed to Richmond that General Henry Alexander Wise’s command be moved from the Kanawha Valley and moved in the direction of Parkersburg and the Northwest Railroad. This would produce a diversion that would allow Garnett to move from Laurel Hill to the B&O Railroad.

It was too late, even in the unlikely event that Richmond would agree to move Wise. The very day—July 11, 1861—that Garnett was again proposing his plan to Richmond, Union Brigadier General Jacob Dolson Cox was launching an invasion into the Kanawha Valley, and McClellan was attacking Garnett’s forces at Rich Mountain, while Brigadier General Thomas Armstrong Morris confronted him at Laurel Hill.

McClellan launched a two-pronged movement in which he hoped to trap Garnett, who in the Union general’s view, had foolishly divided his army, leaving its two main bodies twenty-three miles apart. Morris’ 4,000-man force from the north (at Philippi) was to hold Garnett’s 4,000 men at Laurel Hill while McClellan led a 7,000-man force from the west that would turn and defeat Pegram’s 1,300 men at Rich Mountain. McClellan’s enthusiasm for the plan was such he was greatly annoyed with subordinates who were less eager. He brutally rebuked Thomas Morris for expressing apprehensions about facing Garnett and the need for more men. McClellan told Morris that if he could not do the job with the men he had, “I must find someone else who will…Do not ask for further re-enforcements. If you do, I shall take it as a request to be relieved from your command and to return to Indiana.” [1]

Standoff at Laurel Hill

Admonished by his superior, Morris moved his command out of Philippi in the middle of the night of July 6 and rushed toward Garnett at Laurel Hill. He did so in such a hurry that much of the baggage and needed provisions were left behind. His adversary had taken up a position behind two hills south of the town of Belington, blocking the turnpike, which ran through the middle of his entrenchments and earthworks of rocks, cut trees and abatis. Garnett’s position was not a strong one and could be more easily turned than the Confederate’s position at Rich Mountain. As Morris neared Belington on July 7, he scattered Confederate pickets with several artillery blasts, seized several hills around the town, and raised a large U.S. flag from a house on Elliott’s Hill.

For nearly a week, amid rain and sun, the two combatants were at a standoff in what some have called the Battle of Belington. Their clashes were limited and casualties were light—a dozen or so— despite sniper fire from trees, occasional infantry and cavalry charges, and exchange of artillery fire. Any territorial gains or losses on the wooded hills south of Belington were meager and temporary, as lost positions were almost immediately re-occupied by the original possessor. On one occasion, it was unclear who was friend and foe: one evening at twilight, four companies of the newly arrived Twenty-third Virginia fired on their approaching reinforcements.

The stalemate at Laurel Hill came to an end on July 11, 1861. That morning Garnett was informed that the enemy was marching to turn Pegram at Rich Mountain. That afternoon Garnett and his men could hear the artillery and musket fire from the battle on that mountain. Later news was received that Federals had seized the top of Rich Mountain cutting off Pegram’s route of retreat to Beverly and Staunton, and imperiling Garnett’s retreat route to those same towns. To buy time, Garnett ordered the 44th Virginia to hold the road, if possible, between Rich Mountain and Beverly by probing and intensely engaging the enemy to give the appearance of an imminent attack; meanwhile, Garnett would begin his withdrawal.

Rich Mountain

Earlier, while sending Morris to distract Garnett from the north, McClellan gathered another force, sending it south by way of Clarksburg to Weston and then eastward by the way of Buckhannon to Rich Mountain. There he set up camp near Roaring Creek, which separated his force from the enemy, who were two miles away at Camp Garnett.

McClellan arrived at the Federal camp on July 9, the same day the Confederate commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Pegram, apparently unaware of the size of his opponent (seven times that of his own), was unsuccessfully seeking General Garnett’s permission to attack. McClellan was more cautious than Pegram and was nervous about fighting his first battle as the commander. Reconnaissance on July 10 revealed that Pegram was strongly fortified at the base of the mountain. A Union frontal assault would be too costly. That night, the Federals found a solution when a young man appeared in their camp; he was attempting to pass through Union lines to return to his home at the mountain gap on the road behind Pegram’s camp.

The youth was David Hart, a Unionist returning from visiting relatives. After being closely examined by Brigadier General William Starke Rosecrans, Hart was taken to see McClellan— along with a plan for turning the enemy. Hart agreed to guide a Federal force to his father’s house over a circuitous route through the forest, around the enemy’s left, to a point on the mountaintop one and half miles from the gap. From there they could follow a rough road to his father’s house. The rough terrain would prevent them from taking artillery. McClellan consented, perhaps reluctantly, to allow Hart to lead Rosecrans with 1,917 men to the mountain gap. From there, less than three miles from the enemy camp, Rosecrans could descend the western slope of the mountain on the turnpike and approach Camp Garnett from the rear. The sound of Rosecrans’ attack would signal McClellan, with the bulk of the Union force, to attack the enemy from the front. Rosecrans planned to attack the rear of Pegram’s works by 10:00 a.m. the next morning, July 11. A company of cavalry was taken to keep McClellan apprised of Rosecrans’ progress in case something happened unexpectedly. A message, carried by a cavalryman, was to be sent every hour.

Things did not go smoothly for the four infantry regiments (the 8th, 10th, 13th, and 19th Ohio) and Captain H. W. Burdsal’s seventy-five cavalrymen. They were to secretly gather at 3:00 a.m., but one regiment sounded assembly and lit fires. It was daylight before the Federal force moved out; this delay, along with their fear that they might have alerted the enemy, caused them to decide it was best to climb the slope much further to the right than had been planned. This lengthened the route. Intermittent rain pelted them from 6:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. as they made their way through what Rosecrans described as “a pathless forest, over rocks and ravines,” with the added difficulty of “using no ax to clear their way to avoid discovery by the enemy.” Eight hours after their start they were halted—wet, hungry and weary—for rest as Rosecrans and Colonel Frederick William Lander reconnoitered the terrain. The Federal force still had not reached the mountaintop. Rosecrans now sent his first and only message to McClellan, telling of his difficulties and stating that because of the roughness of the terrain and the exhaustion of horses, no additional dispatches would be sent until there was “something of importance to communicate.” Frustration led to threats against young Hart, whom Rosecrans said was so scared he was about to leave. Hart seemed to have run off, but might have returned to help guide the soldiers to his father’s house by midafternoon. [2]

Rosecrans’ march to the mountain gap lasted about ten to twelve hours, and in the meantime, the fear that Confederates might learn of his turning movement had become a reality. The night before Rosecrans’ march, sights and sounds—lights flashing, axes chopping, and bugles calls—alerted the Confederates to possible enemy movement. Pegram was afraid he would be attacked from the rear, so he sent two companies to the gap at Hart’s house. The next morning around 9:00 a.m., a Federal courier—who had mistakenly ridden into Pegram’s camp carrying a dispatch from McClellan to Rosecrans—was wounded and captured, and it was revealed to Pegram that a Union turning movement was indeed in progress.

Pegram wrongly assumed this was taking place over a country road to his right and sent one of his force’s artillery pieces and Captain Julius Adolph De Lagnel, Garnett’s chief of artillery, to command a 310-man force at the Rich Mountain pass at Hart’s residence. The force was comprised of two squads of cavalry from the 14th Virginia and six companies of infantry from 20th and 25th Virginia. One company from the 20th, was known as the College Boys, consisting of students from Hampden-Sidney College and commanded by one of their professors, Captain John Mayo Pleasants Atkinson. To further aid in the protection of his rear, Pegram ordered Colonel William C. Scott at Beverly to position his regiment (the 44th Virginia) at the junction of Merritt Road and the Beverly-Buckhannon Turnpike to protect his rear from the enemy’s turning movement.

At 2:30 p.m. on July 11, Rosecrans’ force arrived on the hill to the south overlooking the mountain pass. Half a mile from the Hart farm, Confederate pickets unexpectedly fired upon his skirmishers. The pickets pulled back to their main force at the pass, shouting repeatedly, “Yanks from the South!” The Confederates were expecting an enemy attack from the north. They turned their only artillery piece to the south and opened fire on the oncoming enemy. Union skirmishers fired from behind rocks and trees several hundred yards away at the Confederates, who concentrated their artillery fire of spherical shot at the rate of four per minute upon the main Union force. After a brief time, the Federals withdrew. Twenty minutes later they advanced and renewed the fighting, firing from the protection of the woods. The Confederate gun was pulled a short distance northward across the road to a slope and again commenced firing. Unable to see the enemy, the Confederates fired in the direction of rising smoke that emanated from the edge of the wood. [3]

Thinking they had been successful De Lagnel notified Pegram that they had twice repulsed the enemy and won the fight. This news set off an uproar of cheering at Camp Garnett that was heard by McClellan in his camp just west across Roaring Creek. He too assumed Rosecrans had been defeated. Earlier McClellan had moved his force closer to the enemy fort in anticipation of attacking. Concerned that a frontal assault without Rosecrans attacking from the rear would be costly, McClellan moved his force back to camp and armed even teamsters in case the enemy attacked. In the meantime, a road was being cut to a rise on the enemy left where the next morning McClellan planned for the Union artillery to enfilade Pegram and drive him from his camp.

Rosecrans was far from defeated. His force suffered few casualties in the first two advances—the woods had shielded his men as the shot from the Confederate brass six-pounder flew over their heads. Rosecrans was determined to take the enemy’s six-pounder and overwhelm them with an all-out attack. Some regiments misunderstood his orders and were positioned incorrectly, which caused a delay of nearly three-quarters of an hour. Rosecrans, personally leading one of his regiments, moved his whole force forward. Some men stamped through Hart’s garden near the house as the Union force converged on the Confederates. Southerners who had earlier fired with relative impunity from the windows and chinks between logs of the Hart house were driven from the dwelling as Federals swarmed to the left, center, and especially to the right flank of the Southerners, placing De Lagnel in danger of being cut off from the road to Camp Garnett. Frightened artillery horses pulling the ammunition caisson became unmanageable and stampeded down the road, carrying away their drivers and most of the ammunition. They soon collided with a brass six-pounder being pulled from Camp Garnett, which De Lagnel had requested. Drivers were hurled from their seats, a dozen horses were injured or killed, and their mangled bodies were mixed with smashed equipment as the artillery piece careened down an embankment. (Federals would later capture it.)

Back at the battle site, the Virginians’ situation was desperate. Overwhelmed by vastly greater numbers, the Southerners pulled the six-pounder behind Hart’s barn just north of the road, but attempts to fire the piece proved futile. There were only two artillerymen left. Captain De Lagnel was injured, he was pulled out of the sight of the enemy by a young artilleryman. The wounded captain ordered his men to escape to Beverly if they could. Federals now swarmed over the hastily constructed log works that paralleled the road. One Federal repeatedly bayoneted a wounded Confederate. This infuriated De Lagnel, who attempted to retaliate and struggled to stand, but he lost consciousness and fell down a bank, where he lay, unconscious and undetected, for a couple of hours. The remainders of his command on the left made their way to Beverly. Those on the right returned to Camp Garnett after leaving the main road to escape the enemy’s fire. They left behind thirty-three dead and wounded. Fourteen Federals and sixty Confederate wounded were also scattered over the saddle-shaped terrain of the Hart farm, where the mountain sloped downward from the back of the house to the turnpike and then rose to wooded heights.

Pegram attempted to reverse his sagging fortunes. Arriving at 6:00 p.m. as the three-hour battle was ending, he saw his men fleeing their works at Hart’s. Despite great personal effort he was unable to rally them. Finding the situation hopeless, Pegram hurried back to camp and ordered his regiment’s remaining companies toward the battle site, leaving the right side of the Camp Garnett works totally unmanned. Approximately midway up the mountain, he met the men who had fled from battle down the western slope of the mountain-under the command of Major Nat Tyler waiting in the woods to ambush the enemy. Pegram asked them if they were willing to go back and fight. While the men were responding with a cheer, a captain interrupted, saying, “Colonel Pegram these men are completely demoralized, and will need you to lead them.” Taking his place at the head of the column, Pegram led the men single-file in the rain through what he called “laurel thickets and through almost impossible brushwood” to the top of the mountain, a quarter-mile away from Rosecrans’ right flank. There Pegram was about to position his men to attack when Major Tyler informed him that during the march up the mountain “one of the men in his frightened state had turned around and shot the first sergeant of one of the rear companies, which had caused nearly the whole company to run to the rear.” Soon after a captain told Pegram, “the men were so intensely demoralized that he considered it madness to attempt to lead them into an attack.” Pegram wrote in his official report, “A mere glance at the frightened countenances around” him convinced Pegram that his distressing news was true. It was confirmed by the opinion “of the company commanders around him.” They all agreed with Pegram, who stated, “there was nothing left to do but to send the command under Major Tyler” to join Garnett at Laurel Hill or to Colonel William C. Scott’s regiment, which was believed to be near Beverly. [4]

It was 6:30 p.m. when Pegram sent Tyler’s men northeastward to escape off the mountain. Pegram started back to camp. He frequently lost his way and was thrown from his horse and was injured, so he did not arrive until 11:15 p.m. The situation was becoming desperate. A council of war was breaking up when Pegram arrived. Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan M. Heck, the second in command, had called the meeting and had related Pegram’s orders to hold the camp at all costs. Pegram immediately reconvened the officers, and they concurred it was time to leave. Heck would lead all the able-bodied men over the mountains to join Garnett, while Pegram, battered by his ordeals, would stay behind with the sick.

Totally unaware of the demoralized state of his opponent, Rosecrans feared for his own safety at the mountain gap. He called his men back after they had pursued the fleeing Southerners for only several hundred yards. Darkness was approaching, and it was too late to attack a well-fortified enemy camp almost three miles away that could only be reached by a road described by Pegram as “skirted with almost an impenetrable thicket of underbrush.” Nor did he feel he could head eastward to Beverly, as he was already separated from the main Union force by an enemy whom, he believed, had 5,000 to 8,000 men. McClellan had made no attack, so no help could be expected from him. Rosecrans tried to find a cavalryman to carry a message of his plight to McClellan, but this proved futile. No one who would undertake such a venture could be found. Feeling vulnerable and isolated between an entrenched enemy camp to his west and another unknown force to the east, Rosecrans decided to spend the night on top of the mountain. It was a very dark, cold, and rainy summer night. The wounded of both sides were huddled together in the Hart house and on its porch, and they filled all the outbuilding to protect themselves from the inclement weather. The next morning a detail buried thirty-two Confederate dead in two trenches in or near Hart’s garden. Among those buried were three of the four men of the 25th Virginia who had previously carved their names on two rocks they fought behind. (One of the rocks they fought behind is today known as the Dawson’s Boulder, named for the only survivor of the four, Private George W. Dawson.) [5]

That night was an anxious one for Rosecrans who wrote that his men “turned out six times…on account of the pickets firing on the front, expecting an attack of the enemy.” At 3:00 a.m. welcome news arrived. A prisoner who was brought before Rosecrans revealed that the enemy was attempting to leave. This news led Rosecrans to move on to camp Garnett at daylight, where he found a white flag flying. [6]

Retreat and Disaster

The approximately 170 men, mostly sick and wounded, whom Pegram left behind surrendered to Rosecrans and turned over to him the two remaining artillery pieces, their wagons, the equipment, and the quartermaster’s store. McClellan’s force was positioned a short distance in front of Fort Garnett and was preparing to send artillery to a hill by way of the road they had cut during the night to enfilade the Confederate camp. Amidst their preparations, one of Rosecrans’ cavalrymen reported that the enemy camp had been abandoned. When McClellan sent someone to verity this report, his scout found the camp occupied by Rosecrans. McClellan soon moved out, leaving behind several companies of the 13th Indiana to destroy the Rebel fortifications and bury the dead.

By midday McClellan had moved across Rich Mountain via the gap at Hart’s farm and had occupied Beverly. The most eventful part of the march occurred during a half-hour rest at the site of the previous day’s battle. The soldiers’ eyes were drawn, as if magnetically, to the sobering sight of the dead. Some were half-naked and scattered over the field; others had been placed in a long trench, which was still open.

Colonel Heck had left Camp Garnett at 1:00 a.m. on June 12 with most of the remaining Confederates—except for the disabled—who were west of the mountain, in order to join Garnett. Jedediah HotchKiss, who had recently been appointed Confederate topographical engineer and was known as Professor Hotchkiss, led the way, followed by Captain Robert Doak Lilley’s company of the 25th Virginia. Meanwhile, Pegram, who was nicknamed Little Corporal by his men, changed his mind about staying behind. He sent word for the column to halt so he could lead them. The message never reached Hotchkiss and Lilly’s company and they proceeded forward, separating themselves from the rest of the column. Somewhere behind them was the main body, with the exhausted Pegram, who had a high fever and had to be conveyed over the mountain in a blanket carried by four men.

Frustration and exhaustion would only increase. Three-fourths of his men had no rations, and the rest had only enough for one meal. It took eighteen grueling hours to move twelve miles and cross the mountain to the Tygart Valley. Pegram was told that Garnett was at Leadsville, so he hired a horse and made his way near that town-only to be informed that Garnett had been there, but had fled northeastward, pursued by a large federal force. With no chance of joining Garnett, Pegram returned to his fatigued men. He found them in a state of confusion, firing randomly into the darkness, believing the enemy had surrounded them. Knowing a federal force was above him and McClellan was below him at Beverly, and there was little in the way of food to be obtained on the back roads, their only possible route of escape, Pegram called a council of war. Most agreed with their commander that surrender was the only alternative to starvation, but forty men left during the night rather than surrender. The rest, 600 men, surrendered to McClellan at Beverly on July 13, 1861. When the hungry Confederates were marching, still fully armed, to Beverly to capitulate, they were met by several wagon loads of bread benevolently sent by McClellan.

Some of the Confederates involved in the Rich Mountain battle escaped across Cheat Mountain by way of Huttonsville. They made their way to safety before McClellan seized Beverly. First was William Scott and his 44th Virginia infantry, then Nat Tyler with part of Pegram’s command, followed by Jed Hotchkiss with fifty men who had led the evacuation from Camp Garnett. While crossing Rich Mountain, they encountered darkness, drenching rains, fallen trees, dense thickets and precipices. These obstacles were burdensome for Hotchkiss and his small band, as well as the rest of Pegram’s retreating force.

The day Pegram surrendered, McClellan moved through Huttonsville to secure Cheat Mountain Summit. Finding no Confederate force in the vicinity of the mountain pass, McClellan became convinced that the retreating enemy would not stop until they reached Staunton. He moved his force back to Huttonsville. A few days later on July 15, leaving two regiments of infantry, a battery, and a cavalry company at Huttonsville to patrol Cheat Mountain Summit, he moved the rest of his force back to Beverly. He felt he was in a better position there to move rapidly in any direction necessary.

In the meantime, Garnett and his men north of Beverly were having a difficult time escaping; at Beverly on the morning of July 12, they had mistaken fleeing Confederates for the enemy. This mistake cost the Confederates a relative easy and shorter escape southward through the Tygart Valley to Cheat Mountain. (McClellan would not occupy the town until that afternoon.) Garnett instead moved northeastward toward Red House, in the panhandle of Maryland, in an attempt to escape the enemy from above and below.

It was a difficult time. Rain poured down on them, turning the road into a nearly bottomless pit of soupy mud that resisted every exhausting step. Wagons fell off narrow, winding, slippery roads and crashed into trees below. The farther they went the greater the disorganization, especially in the rear of the line, which spread out for ten miles. Many discarded their weapons. Shoeless soldiers limped along, leaving bloodstained paths. The sick crawled into whatever structures they could find, from houses to barns to pigpens, where they lay for several days until taken prisoner by Northern patrols. Starvation forced able-bodied men away from their hiding places in the woods to give themselves up. From Red House, hungry Confederates, in disarray and panic, feared the enemy was upon them. They moved south, back into Virginia, through a valley seam between the formidable mountain ranges that prevented direct eastern movement. Men became separated, included the rear guard, the 1st Georgia, which was compelled to climb over a steep mountain, wandering if they would ever again see those they had left at home. A father and son in this group attempted to ease the pain of hunger after going without food for four days; they shared a one-inch tallow candle found in the father’s knapsack. Finally, on July 19, after an arduous and circuitous eight-day trip of 150 miles, and after wading through rivers two dozen times, the remnants of Garnett’s bedraggled army reached Monterey. Stragglers continued to arrive for the next week. They had escaped the Federals, but their weakened bodies now had to cope with outbreaks of measles and mumps. They had escaped, but they lost their commander early in their retreat at Corrick’s Ford and had been pursued by two Federal forces in McClellan’s attempt to trap them.

While Confederate authorities struggled with the crisis in western Virginia, the authorities in Washington struggled with the problems resulting from the Union disaster at Bull Run. A shaken Washington would turn to the North’s first victorious military war hero. McClellan had driven the enemy beyond Cheat Mountain as well as away from the B&O and Northwestern Virginia Railroads. He was the man of the hour. Everywhere he went crowds gathered to look upon their new savior. Such popularity amazed him, but the rigors of war would soon dim his shining star. The victory at Rich Mountain led to the creation of the state of West Virginia and the elevation of George McClellan to general-in-chief of all Union forces.

- [1] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 2, p. 229 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 2, 229).

- [2] Ibid., 215.

- [3] Fritz Haselberger, Yanks from the South (Baltimore, MD: Past Glories, 1987), 137.

- [4] O.R., I, 2, 265.

- [5] Ibid.

- [6] “Testimony of Major General W. S. Rosecrans, April 22, 1865,” in Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, H.R. Rep. No. 38(2) (1865) part 5, Rosecrans’s Campaigns, 5.

If you can read only one book:

Poland Jr., Charles P. The Glories of War: Small Battles and Early Heroes of 1861. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2004.

Books:

Haselberger, Fritz. Yanks from the South. Chelsea, MI: Book Crafters, 1987.

Newell, Clayton R. Lee vs. McClellan. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, 1996.

Zinn, Jack. The Battle of Rich Mountain. Parsons, WV: McLean Print Co, 1971.

Organizations:

Rich Mountain Battlefield Foundation

The Rich Mountain Battlefield Foundation is working to preserve the Rich Mountain Battlefield and Camp Garnett.

Rich Mountain Battlefield Civil War Site & Visitor Center

The Rich Mountain Battlefield Civil War Site & Visitor Center is located west of Beverly WV and features interpretive signs, walking tours and a picnic area. The Beverly Heritage Center is the interpretive center for the site and is located at 4 Court Street Beverly WV 26253, telephone 304 637 7424. Hours are seasonal.

Web Resources:

The History of the Battle of Rich Mountain is a useful overview of the battle produced by the Rich Mountain Battlefield Foundation.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.