The Jones-Imboden Raid

by Darrell L. Collins

In April 1863 Confederate forces launched a raid into the new state of West Virginia designed to wreak economic havoc on the region.

In Washington on April 20, 1863 President Abraham Lincoln signed the proclamation that gave his formal approval to the admission of West Virginia as the thirty-fifth state of the union. Out in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia that same day, by coincidence and intent in equal measure, Confederate forces numbering more than 6,000 men prepared to launch into the new state what some would label a raid designed to wreak economic havoc on the region, and what others would consider to be nothing less than an invasion for the purpose of challenging the viability of the new state.

When Virginia had pulled out of the union two years before, the state’s western counties, from the Allegheny Mountains to the Ohio River, having far fewer slaves than the eastern Tidewater and Piedmont regions, and being more generally oriented north geographically, culturally, and economically, strongly objected to the act of secession. Mass unionist meetings sprang up throughout the disgruntled region, ultimately producing the movement to form first, a loyal Virginia government, and then a separate state altogether. This is not to say, however, that the western counties, particularly those lying along the north-south spine of the Alleghenies, did not have Southern sympathies. Several had a majority of such, all of which produced in the area a vicious form of warfare that included the bushwhacker, the partisan, and the guerilla, what we might label today as terrorists.[1]

The plan for the raid/invasion, as originally proposed by local partisan leader Captain John “Hanse” McNeill and approved by Confederate Secretary of War James Alexander Seddon, was quite simple—to use a relatively small force to make a lightning strike at what was perceived to be the most crucial accessible point on the line of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Stretching 379 miles from Baltimore in the east to Wheeling on the Ohio River in the west, the B&O was arguably the most important line serving the Union war effort, providing from the Midwest vast amounts of men and materiel for the Army of the Potomac. Destroying the bridge and two viaducts at Rowelsburg on the Cheat River in Preston County, less than forty miles from the Pennsylvania border, and some eighty-five miles southeast of Wheeling, promised to inflict severe damage on the line that would put it out of commission for some considerable length of time.

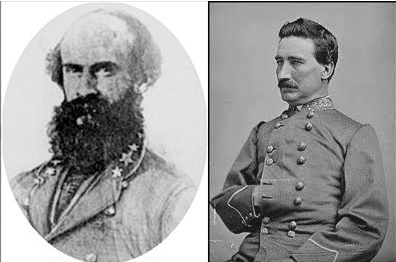

Brigadier General John Daniel Imboden, however, had other ideas. An attorney practicing in Staunton before the war, Imboden helped raise and became commander of what now was styled the Northwest Brigade, some 1,800 men of the Sixty-second Virginia Mounted Infantry, 18th Virginia Cavalry, and McClanahan’s Virginia Battery. He envisioned the proposed strike on Rowelsburg as a grand opportunity to not only hit the B&O, but to enter the western counties as a liberator from “Yankee oppression,” that would in turn disrupt the formation of the new government of the “so-called” state of West Virginia, while reaping a great harvest of men, horses, and cattle for General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Lee heartily approved of this bold new expanded plan.[2]

Brigadier General William Edmondson “Grumble” Jones, however, had other ideas. Originally assigned by Lee to act as a diversion from the lower Shenandoah Valley in favor of Imboden, Jones now wanted to reverse those roles. He argued, reasonably enough, that his famed Laurel Brigade of cavalry (6th Virginia Cavalry, 7th Virginia Cavalry, 11th Virginia Cavalry, 12th Virginia Cavalry; plus the 34th Battalion Virginia Cavalry, 35th Battalion Virginia Cavalry, and 1st Battalion Maryland Cavalry, some 2,200 men altogether) had a far better chance of success than Imboden’s relatively untried troops. After weeks of such planning and haggling, his argument won the day and the great adventure began on April 20.

Reinforced by two regiments sent from Lee’s army, the 25th and the 31st Virginia Infantry Regiments, so called trans-Allegheny regiments composed mostly of men from the western counties, Imboden set out from near Staunton in the Shenandoah, crossed the mountains, and on the April 24 descended on the small town of Beverly in Randolph County. After a brief fight, he drove off a detachment of the 4th Separate Brigade, some 878 West Virginia and Ohio troops led by Colonel George Robert Latham, and seized the town. Four days later, he occupied Buckhannon in Upshur County, some twenty miles northwest of Beverly. Now Imboden, having created his assigned diversion, sat and waited for Grumble Jones to do his job.

On April 21, Jones set out from near Harrisonburg in the lower Shenandoah. After forcing his way past some eighty-six stubborn Illinois and West Virginia soldiers holed up in two sturdy log structures at Greenland Gap, he pushed on to Altamont and Oakland, where he inflicted his first damage on the B&O. On April 26, he reached Rowelsburg, the primary objective of the entire expedition. A determined effort probably would have won him the great prize, but Jones was somewhat inexplicably turned away by the hasty assessment that the place was too well defended.

Unwilling to admit failure, he pushed on to Morgantown, then Fairmont, where he brought down the massive 615-foot iron bridge, then on to Weston, scooping up horses and cattle on the way while destroying track and bridges owned by the B&O. On May 9, he entered Burning Springs, only forty-two miles from Parkersburg and the Ohio border. Not part of the original plan, Burning Springs proved to be his greatest success, though barely recognized as such then and since. He burned some 20,000 barrels of oil, and severely crippled for some time the production capacity of the nearby oilfields. After a brief rendezvous with Imboden at Summersville on May 14, both commands were back home in the Shenandoah Valley by the May 25.

In their official reports (and the general, congratulatory order Imboden issued to his men) both commanders proudly and loudly proclaimed the expedition, despite its many hardships, to be a great success. Both commands indeed had endured much suffering with little open complaint, but was it worth it? How successful were Imboden and Jones in realizing the major objectives they set out to achieve on April 20?

Imboden stated that he captured some 3,100 head of cattle, whereby he proudly declared that he had saved the government about $300,000 in purchasing costs. Jones brought in about 1,200 more head. Jones’ and Imboden’s men consumed some of these animals, others went to the Department of Western Virginia, but the overwhelming majority were put out to pasture in the friendly counties of Pocahontas, Greenbrier, Monroe, and Augusta. Lee probably used the West Virginia beeves to feed his men over the winter, thus rendering at least this aspect of the raid a moderate success.

Horses were another matter. Jones reaped the greatest harvest, taking some 1,200 to 1,500. Imboden gave no figure on the number he took, instead placing an estimate of $100,000 on their value, so probably a few hundred animals were captured. But all these barely offset the terrible losses sustained by both commands. Hundreds of horses gave out along the way and many of those that made it back to the Shenandoah Valley were unfit for further service for some time, if not indefinitely. The expenditure thus proved hardly worth the gain, making for a very small net profit.

Almost the same might be said of the effort to gather in new recruits. The number fell far short of Imboden’s prediction in March of “several thousand.” Overestimating Southern support in West Virginia while underestimating the alienating impact of the raid, even among sympathizers, he took in not more than 500 new enlistments. Jones received perhaps a few dozen more. “In this respect we were all disappointed,” Imboden bitterly admitted in his report. “The people now remaining in the northwest are, to all intents and purposes, a conquered people. Their spirit is broken by tyranny where they are true to our cause, and those who are against us are the blackest hearted, most despicable villains upon the continent.” And as with the horses, these modest gains were largely if not wholly offset by the losses sustained along the way, mostly, surprisingly and ironically enough, by desertion.[3]

What about the destruction of B&O property, particularly its bridges, and the subsequent disruption of traffic along the line? Jones claimed to have destroyed sixteen bridges, Imboden eight more, and the Federals preemptively brought down two, making for twenty-six altogether. Having learned from past experience, the officers of the B&O (not the Federal government) had taken remarkable precautions to protect the property of their company, even going so far as to have wooden duplicates made ready for the quick replacement of bridges along the line. With supreme organization and foresight, they had gathered and stockpiled all the necessary material to deal with such an emergency. Sometimes within only hours, therefore, after the rebels had left the scene, workers swarmed in like bees to begin repairing the damage. Thus a mere ten days after the raiders began their work of destruction, the entire B&O main line in West Virginia had reopened, save for the gap at Fairmont. For ten days more at that place passengers and freight crossed the West Fork of the Monongahela on ferries and pontoons. On May 14, a special large work force completed a temporary wood trestle to replace the fallen 615-foot iron bridge. Thus the destruction wrought by Jones and Imboden on the rail line proved to be little more than an annoying inconvenience.

How successful was the expedition in destroying and capturing the Union forces scattered throughout western Virginia? Grumble Jones reported that his command had killed twenty-five to thirty of the enemy, wounded perhaps three times that many, and captured with their arms nearly 700 soldiers, militiamen, and home guards. Adding the few casualties inflicted by Imboden’s command, Union losses amounted to around 800 men. Combined reported Confederate losses, not counting desertions, amounted to eighty-three men, a figure probably too low, but the overall score greatly favored the Southerners. Nonetheless, this hardly can be considered a stunning success.

What makes these casualty figures truly remarkable, however, is the fact that they occurred in the face of incredible odds. Jones and Imboden commanded no more than 6,000 men between them. When the Confederates entered West Virginia, Brigadier General Benjamin Franklin Kelley’s division of 10,000 men was positioned at various points along the B&O line, from Harper’s Ferry to the Ohio River. Brigadier General Benjamin Stone Roberts’ 2,500 men of the Fourth Separate Brigade held various positions throughout the state, and perhaps 3,000 more Federals were in the Kanawha Valley under Brigadier General Eliakim Parker Scammon. Moreover, as the raid progressed those odds increased dramatically. From Winchester, Brigadier General Robert Huston Milroy sent several detachments to Clarksburg; from the Department of the Ohio Major General Ambrose Burnside sent what troops he could spare to Marietta and Bellaire, and he arranged for two gunboats to speed up the Ohio River for Parkersburg; thousands of militiamen and home guards reported for duty in eastern Ohio, western Pennsylvania, and throughout West Virginia, with many being sent on to Clarksburg, Fairmont, and Grafton. Thus by the end of the first week in May, perhaps as many as 25,000 of the enemy had been roused against Jones and Imboden.[4]

These four-to-one odds, however, were evened considerably by those fortuitous circumstances that so often appear during war, in this case the most influential being the right combination of skillful daring and resourcefulness on the one side, with the timidity and incompetence on the other. The swift moving Confederate forces that seemed to be everywhere in such great numbers, striking several targets simultaneously, baffled and confused the Union commanders to the point of paralyzing impotence. This kept the initiative in Confederate hands throughout the raid, whereby Imboden drove the Federals out of Beverly, Philippi, and Buckhannon, while Jones conducted a bold counter-clockwise sweep across the new state, both Confederate commanders along the way easily frustrating the Federal defensive strategy of anticipated interception. But such bold audacity, so successfully executed, produced the effect of ensuring, by way of Union reinforcement and reorganization in the area, that such Confederate success never again occurred in West Virginia.

The raid’s greatest failure, as measured against its initial lofty expectations, was the attempt, or at least the hope, to bring down the Wheeling government and thereby open the way for nothing less than the liberation of the oppressed people of northwestern Virginia. Other than the temporary, brief disruption of political conventions at Parkersburg and Wheeling, the Confederates achieved nothing in that regard. Ironically, the raid for the most part produced quite the opposite effect, whereby its destructions and confiscations crystallized and hardened opinion against the Southern cause, even among some sympathizers. Moreover, the raid created a severe backlash, with loud, angry and effective calls for increased repressive measures against Southern sympathizers. Imboden had come to avenge and bring relief from such oppression, only to see it intensified in his wake.

Jones and Imboden had departed West Virginia, leaving behind them death, destruction, and bitterness. “The rebels have now left for Dixie,” the Wheeling Intelligencer scornfully remarked on May 8, “with the just execrations of all loyal Virginians and most of their former sympathizers. Also, their father the devil left with them. May West Virginia never be again disgraced with such greasy Southern ‘chivaly.’”

- [1] A personal illustrative example, passed down to me through my family, concerns the time a Union soldier stopped at the farm home of my great grandparents on the Greenbrier River in Pocahontas County to ask for a drink of water. While standing in the doorway speaking to my great grandmother he was shot dead by an unseen sniper firing from the nearby woods. My father recalled that as a boy he remembered seeing bloodstains on the wood floor of the house some sixty years after the event, and the soldier’s grave is clearly marked in the nearby family cemetery to this day. [2] United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 25, part 2, p. 652-3 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 25, pt. 2, 652-3).

- [3] O.R., I, 25, pt. 2, 653; O.R., I, 25, pt. 1, 104.

- [4] O.R., I, 25, pt. 1, 90-3.

If you can read only one book:

Collins, Darrell L. The Jones-Imboden Raid. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007.

Books:

Boehm, Robert B. “The Jones –Imboden Raid Through West Virginia,” in Civil War Times Illustrated 3, Issue 2 (May 1964): 15-22.

French, Steven. “The Jones-Imboden Raid,” in The Blue and Gray Education Society Paper # 10 (March 2001).

Summers, Festus P. “The Imboden Raid and Its Effects,” in West Virginia History 47 (1988).

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.