The Mexican American War

by Michael A. Morrison

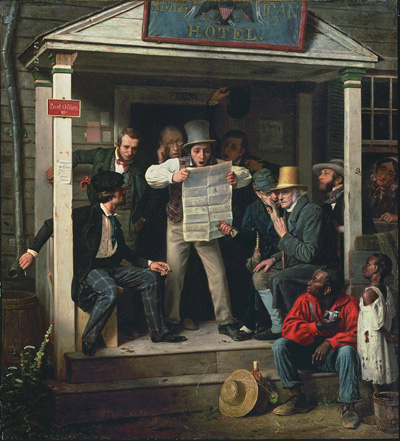

Territories obtained in the Mexican American War of 1848 caused further sectional strife over the expansion of slavery in the ante bellum period.

The origins of the Mexican War are rooted in the rapid expansion of American settlers west and the annexation of the Texas Republic to the United States in 1845. The ideological seeds of the American Civil War, in turn, were sown during that conflict. In their quest to expand Thomas Jefferson’s and Andrew Jackson’s empire of liberty, Americans succeeded in rending the Republic in 1860 over the question of the expansion of slavery into the newly acquired territories of the West. And it was the war with Mexico, the first step in President James Knox Polk’s quest for a continental empire for free white men, in which the first skirmishes into the commonly owned territories between North and South over slavery’s restriction or expansion were fought.

Texans had achieved their independence from Mexico in 1836 when, under duress, General Santa Anna signed a treaty that brought the conflict with the revolutionaries to an end. Now free and having withdrawn safely across the Rio Grande, Santa Anna and the Mexican government immediately repudiated that agreement. Texas was a prominent element in President Andrew Jackson’s empire of liberty. Yet the threat of war with Mexico, charges of presidential complicity in the revolt, the possible growth of sectional tensions issuing from the addition of slaveholding Texas to the Union, and unwillingness to jeopardize the election of Martin Van Buren stayed his hand. Continued agitation in and out of Texas for annexation and mounting evidence of widespread American support for expansion persuaded the Senate to recommend formal recognition of the republic on March 1, 1837. Recognition was formalized by the appointment and confirmation of Alcée la Branche as chargé to the republic on March 3—Jackson’s last day as president. President Martin Van Buren, Andrew Jackson’s successor, would go no further. Preoccupied with an economic depression, he believed that annexation would strain a Union seriously distracted by severe financial problems and rising agitation over slavery.[1]

Poor John Tyler. He was a president without a party. Having assumed the presidency in 1841 upon the death of William Henry Harrison (Van Buren’s successor who lived only one month after his inauguration), Tyler, a former Democrat, broke with Henry Clay and the Whigs over his vetoes of bills that would have re-chartered the Bank of the United States. In retaliation, Clay then had Tyler read out of the party and banished into the political darkness. With a diminished and diminishing “corporal’s guard” of supporters, Tyler was in need of an issue upon which he could run for reelection in 1844. Understanding the power and attraction of western expansion, Tyler seized on the question of Texas annexation to restore his lost prestige and popularity. After protracted negotiations a treaty of annexation was concluded in April 1844. Tyler sent it along to the Senate later that month.

Tyler’s treaty and the question of widespread territorial expansion generally generated a debate in the chamber that produced both heat and light. Democrats, most of whom favored annexation, feared that economic dependency and wage slavery were increasingly jeopardizing personal independence. They believed that the annexation of Texas and the addition of thousands of square miles of territory to the Union addressed this most important requirement for republican freedom. Gauging the effect of Tyler’s treaty of annexation on the public (from the president’s perspective its intent of course was to ensure his reelection), a supporter contended that the impact of cheap territory in Texas “would be to invite a large number of individuals who had settled in the eastern cities, who were half-starved and dependent on those who employed them, to go West, where with little funds, they could secure a small farm on which to subsist and . . . get rid of that feeling of dependence which made them slaves.” If the United States annexed Texas, a Mississippi editor predicted, “many a poor man that has been a renter for half a life time will be able to become a land holder very soon. . . . To all such the annexation of Texas is a measure of vital importance."[2]

Whigs, fearing the economic effect of a widely dispersed population chained to and enslaved by a subsistence economy on small farms, opposed rapid western expansion. As the population grew increasingly nomadic, they would develop a distaste for peaceful, civilizing occupations. Whigs saw Texas annexation as but another appeal, however powerful—and it was—calculated to pander to the prejudices of the laboring classes to ensure Tyler’s election. Worse, should Democrats support it, the treaty could be the means of their victory in 1844. Annexation would “array, in most unnatural hostility, the poor against the rich—the laborer against the employer—the mechanic against the merchant—the farmer against the manufacturer.” Put simply, Texas annexation would produce economic dependency, depopulation of the East, concentrated land holdings, and, as a result, class conflict. Standing solidly against Tyler’s treaty of annexation, Whigs joined by a handful of free-soil Democrats killed it.[3]

Despite the Whigs’ best efforts to quash the Texas question, it became the dominant issue in the 1844 presidential campaign. The presumptive presidential candidates of both parties—Martin Van Buren and Henry Clay—came out against immediate annexation. In April while the Senate was debating the treaty, Van Buren declared in a letter published in the Washington Globe that annexation would be inexpedient as long as Mexico opposed it. He would however favor the addition of Texas to the Union if that state and Mexico resolved their differences and if a majority of Americans and senators supported annexation. The former president’s re-nomination prospects were already dim. His opposition to annexation did nothing to improve them. Van Buren was not well liked, the Democratic Party was rent with factionalism, and spring elections at the state level had gone badly. Not surprisingly the Whigs relished the prospects of his candidacy. They were to be disappointed. At the party’s nominating convention in May the party threw Van Buren overboard and nominated James K. Polk of Tennessee. Polk had few enemies and was an enthusiastic supporter of Texas annexation. He ran on a platform that called for the “re-annexation” of Texas and the “re-occupation” of the Oregon territory. Tyler’s candidacy, already clouded by the Senate’s defeat of his handiwork, found his prospects for election in total eclipse following the Democratic convention. He ended his third-party bid in August.[4]

The Whigs ran Clay as expected. And as expected he ran on a platform that emphasized economic issues—a Bank of the United States, a judicious tariff, and federally funded internal improvements. He and other party leaders wished rather than hoped that the Texas issue would go away. It did not. Momentum for expansion among the electorate seemed to build. Clay had already publicly opposed annexation in the spring, fearing as he did that it would precipitate a war with Mexico and inject slavery into the national political discourse. Finding it difficult to restructure the campaign debate along established economic lines, Clay modified his position on Texas in July. In two published letters, he reasserted that his primary goal was to preserve the Union but that “far from having any personal objection to the annexation of Texas, I should be glad to see it, without dishonor—without, war, with the common consent of the Union, and upon just and fair terms.”[5]

Clay could have saved his paper and ink. Polk carried the election by 170 electoral votes to 105. His margin in the popular vote was slim, capturing a narrow plurality of 38,367 out of more than 2.7 million cast. At the county level Democrats increased their hold in every section including New England. Widespread economic gains in the North and Northwest suggest that Democrats there understood Texas annexation and expansion generally to be consistent with the party’s established principles. In the South Whigs did well, increasing their totals from 1840 in every state except North Carolina, Alabama, and Tennessee.

Tyler, believing that the outcome of the election was a mandate for its ratification, pressed Congress to approve a joint resolution that was largely a restatement of the rejected treaty’s terms. It did in late January 1845. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee rejected the House’s proposition. Both houses finally agreed to a proposal that empowered the president to offer Texas the choice of the terms in the joint resolution of annexation or the negotiation of a new treaty of annexation. Most supporters of annexation assumed President-elect Polk would carry out the proposal. On the last night of his administration, Tyler, vindicated and vain, ordered the American chargé in Texas to present the House resolution to the Texas government at once. Texas ratified the resolution in October and entered the Union in December.

As Polk assumed his office in March 1845 Mexico, which had not recognized Texas independence, broke off diplomatic relations. Ultimately the breach between the two nations suited the aggressive president’s purposes. He was determined to make the United States an ocean-bound republic. Polk preferred to acquire his empire of liberty through negotiation or coercion and purchase. The president, however, was given to impatience, intrigue, and political calculation to enhance his own personal and the nation’s geopolitical goals. By turns stolid, sober-minded, disciplined, and politically willful, he was possessed of an iron-willed perseverance. As a recent biographer has observed, Polk was “a smaller-than-life figure [who] harbored larger-than-life ambitions.”[6]

And so he did. In the fall of 1845 Polk began forcefully to pressure Mexico into ceding Upper California and New Mexico in exchange for a satisfactory adjustment of the Texas boundary, the surrender of American claims against Mexico, and an appropriately large compensatory payment from the United States. In September he decided to send Representative John Slidell (Louisiana), to conduct the negotiations. Slidell, who had no diplomatic experience, was an ardent supporter of slavery, Andrew Jackson, and the president. Polk reiterated his goal that Upper California and New Mexico be acquired but added that the most agreeable boundary would be the Rio Grande River then west to the Pacific Ocean. And he informed Slidell that he was willing to go as high as $25 million if the Mexican government would agree to dismember the nation. Not surprisingly, Mexico refused to receive the Slidell mission. Slidell, who thought Mexico “feeble and distracted,” advised the president that “a war would probably be the best mode of settling our affairs with Mexico.” Ironically, Polk had already come to the conclusion that a show of force would prevent war inasmuch as in his view Mexico was weak and financially and morally bankrupt. He now decided to act on his own prejudices and Slidell’s suggestion.[7]

In January 1846 the president ordered General Zachary Taylor’s forces, which had been camped at Corpus Christi, to the Rio Grande. The river constituted the extreme, dubious, and diplomatically indefensible Texas claim of its border with Mexico. In late April, 2,000 Mexican troops crossed the river trapping a detachment of American dragoons. Vastly outnumbered, the detachment of 70 surrendered. In the brief but fierce skirmish, 16 dragoons were killed and 5 wounded. News of the attack reached Washington in May. Polk, asserting that “war exists by the act of Mexico herself,” asked Congress to recognize (rather than declare) that a state of war existed between the nations. So it did on May 13 by a vote of 40-2 in the Senate and 174-14 in the House.

Polk’s bellicose diplomacy was particularly foolhardy and rash given the depleted and unprepared state of U.S. forces. Although Mexico’s army outnumbered U. S. forces by nearly a 5 to 1 ratio, it too was unprepared for a sustained conflict. Mexican generals faced the same problems as did U.S. commanders with training, discipline, and munitions. Thus in many ways and despite the original numerical imbalance, these opposing forces were mirror images of each other. Still the war went well for American forces in 1846. Taylor captured Monterrey in September. The conquest of California under John Frémont was underway before news of the Mexican conflict arrived. In the summer of 1846 Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny captured Santa Fe and then moved his forces into southern California. By fall the conquest of California was complete.[8]

Polk made it clear to his cabinet that the price of peace would be territorial acquisitions in the West, though he was vague about the extent of the territorial settlement. Polk would later insist that the nation had not gone to war for “conquest” and without irony added that the United States would insist on “indemnification for the past and security for the future.” Indemnification and security would come in the form of acquisition of at least New Mexico and California. It would also come at a great political and human cost. August 8, 1846, he sent a message to Congress expressing his desire to end the two-month-old war with Mexico on a basis of peace that was honorable to both parties. The president requested an appropriation of $2 million (down from the $25 million he proposed to Slidell) to pay for any territorial concessions that might be made by Mexico. That evening the House took up the request.

Whigs immediately took the floor to condemn the president and scorn his message of peace. Suspecting as they did that Polk provoked a conflict with Mexico to seize what he could not acquire peacefully, they charged that the war was unnecessary and unjustifiable. The $2 million was not to buy a peace but to pay for a land grab. After four Whigs pummeled the president along these lines, the chair recognized David Wilmot, a first-term Democrat from northern Pennsylvania. Wilmot, a supporter of the war, asserted the president’s actions were necessary and proper. He hailed the president’s willingness to negotiate an honorable peace. To that end, Wilmot offered an amendment to the appropriation bill that as a fundamental condition for any acquisition of territory from the Mexican Republic “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory.” In one parliamentary stroke the twin questions of territorial expansion and slavery restriction were joined. As a Whig editor observed at the time, Wilmot’s proviso “brought to a head the great question which is about to divide the American people.”[9]

Wilmot spoke for a number of northern Democrats who were dismayed by what they considered to be a southern tilt in the Polk administration. Northern and eastern Democrats opposed the reductions in duties in the tariff of 1846. The president’s veto of a river and harbors bill incensed western Democrats. And Polk’s willingness to compromise on the Oregon dispute with England, ceding American claims north of the 49th parallel, outraged Democrats in the Old Northwest who had insisted on a boundary of 54º40'. Although these alienated Democrats supported the war, they and their constituents were troubled by this southern president’s plan for land acquired from Mexico. As Eric Foner has astutely argued, Wilmot’s proviso was at one level an expression of alienation and frustration by northern Democrats. At another, it was an attempt to quell growing free-state opposition to the war.[10]

Political principles and ideology also informed the logic of the proviso. These strict-construction Democrats argued that the national government lacked the power to create local institutions such as slavery in the national domain. Adopting the language of the Northwest Ordinance, Wilmot also insisted that free territory would be devoted to the expansion of American free institutions. These restrictionists also insisted that the defense of individual liberty, which lay at the heart of the proviso, also motivated the Founding Fathers in their revolt against England. Just as those revolutionaries defended their autonomy from the despotic encroachments of a distant government, so too would supporters of the proviso defend western settlers from the evils of slavery and the pretensions of slaveholders.

Southerners responded that if individual liberty constituted one of the animating objects of the American political system so did the principle of equality: the equality of slaveholders under the Constitution and of the slave states within the Union. Restriction, they contended, would reduce southern citizens—slaveholders and non-slaveholders alike—to a second-class, degraded status. Wilmot’s proviso would be the means of their enslavement within the Union. Southerners would oppose this threat to their equality just as the revolutionary generation had resisted British efforts to reduce the colonies to a condition of vassalage within the empire. The proviso, then, signaled an abandonment of that revolutionary heritage and the resuscitation of that eternal struggle between tyrannical majorities and abused minorities.

Although the House of Representatives passed the appropriation bill with Wilmot’s amendment attached in a vote along sectional lines, the Senate failed to act on Polk’s request before Congress adjourned. In the next session when the president asked for $3 million to end the war and acquire territory as the price of peace, both the Senate and House rejected the slavery restriction amendment—with voting again along sectional lines. Nonetheless slavery restriction (or extension) became the political issue that would be debated and divide the American people North and South in the coming decade, lead to the formation of the Republican party, and secure Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 which itself provided the grounds and the rationale for secession of the South.

Opposition to the war and to the imperious Polk’s imperial republic would also extend beyond and broadened established party lines. The demand for slavery restriction made political antislavery a potentially broad-based platform that would unite Liberty Party and other reformers in the North with antislavery Whigs and free-soil Democrats. The effect if not the intent of Wilmot’s proviso was to marginalize Garrisonian abolitionists at the same time it it brought the issue of slavery to the fore front in political discourse through opposition to the war and to territorial expansion. The territorial question that would sectionalize the revolutionary political heritage would also make clear, distinct, and permanent the gulf in the political culture of the abolitionist movement. “We need to get back to the true spirit of the revolution—to those great principles on which the nation declared itself free and independent,” a Liberty Party supporter asserted. “The hope of our country lies in resuscitating the great principles of law—the great doctrines of the Declaration of ’76 and of the Constitution of ’89.”[11]

From the spring to the fall of 1847 American troops led by Taylor and Major General Winfield Scott won a series of victories at Buena Vista, Vera Cruz, Cerro Gordo, Contreras, Churubusco, Molino del Rey, and Chapultepec. By mid-September, Scott had entered and occupied the capital of Mexico City and the “Halls of the Montezumas.” Still the Mexican government would not surrender or negotiate a peace. In fact civilian attacks on occupying American forces grew more widespread and violent. “Mexico is an ugly enemy,” a disgusted Daniel Webster scorned. “She will not treat--& she will not retreat.” By the late fall of 1847, the American public, led by the Democratic Party, became more rabid in its demand that the United States annex all or most of Mexico. The irascible Polk’s imperial vision had by then come to encompass Baja California and the northern departments of Mexico. In April he had dispatched Nicholas Trist, a State Department clerk, a loyal Democrat, and a devoted companion and confidant of Thomas Jefferson (whose granddaughter Trist married), to Mexico to negotiate a peace the price of which would be extensive territorial acquisitions.[12]

Although most Whigs (save for the “immortal 14”) had cravenly voted to recognize that a state of war existed between the United States and Mexico, as a party they continued to criticize Polk and condemn the conflict. Charging Polk with executive usurpation in fomenting the conflict with Mexico (Congress never formally declared war), they asserted that wars of conquest were inconsistent with the spirit of American institutions. Once embarked on a career of territorial aggrandizement, they argued, Americans would become filibusters, giving up the peaceful pursuits of industry and thereby undermining the social basis of republican government. Forced to rule distant provinces like conquered territories, the United States would compel other nations to adopt our form of government. Territorial aggrandizement would not only incorporate hostile peoples, Whigs claimed, it would integrate into the fabric of American government and society inferior races. Whig antiwar sentiment had a hard edge.[13]

Accordingly in early 1847 Senator John Berrien of Georgia added his amendment to the administration’s request for a $3 million to make peace with Mexico that the Congress’s intent in making the appropriation would not lead to the dismemberment of that republic. At first glance, Berrien’s “no territory” proposal seems to be at least an evasion of responsibility and reality. At most, and given the success of U.S. forces in the field and the growing appetite of the administration and the public for more—not less—territorial acquisitions, his proviso seems laughable if not insane. But Berrien spoke for Whigs North and South who wished to force the slavery issue introduced by Wilmot’s initiative out of national politics to preserve the integrity of the party system, the Constitution, and the Union. Bloated empires, scattered settlements, and alien peoples weakened the bonds of Union; slavery agitation promised to sever them.

Unhappily for Whigs—and especially Polk—the president had dispatched an envoy to Mexico who had a conscience and a spirit of independence. Moreover Trist had never forgotten and had internalized Thomas Jefferson’s personal pole stars of justice and morality, neither of which the diplomat believed applied to this war. In October 1847 Polk recalled his peace emissary primarily because he and his cabinet were convinced that Mexico did not intend to bargain in good faith or wanted peace. Rather than return to Washington, Trist sent an infuriating (to Polk) message in which he claimed that continued negotiations would result in an accord with Mexico. It was his moral duty, Trist wrote, to ignore the recall and remain in Mexico as a private citizen to continue negotiations. So he did.

On February 2, 1848, Trist and representatives of the Mexican government signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ending the Mexican-American War. By terms of the agreement, Mexico gave up all claims to Texas above the Rio Grande and ceded New Mexico and California. In return for the cession of 619,000 square miles of territory, the United States agreed to pay Mexico $15 million and assume the claims of American citizens against that government up to $3.25 million. Including Texas, the United States had acquired approximately half of Mexico.

The terms of the treaty put Polk on the horns of a dilemma. The treaty conformed generally to his original instructions to Trist, and the ceded territory included his major goals at the war’s outset. The price of peace seemed reasonable. But Polk’s own territorial ambitions and those of many in his party now went beyond New Mexico and Upper California. Yet the president realized that Whigs, free-soil Democrats, and Liberty party members were fully arrayed against the administration and the war. If he were now to reject a treaty made on his own stated terms, Polk anticipated that Congress would grant neither men nor money to sustain American forces in the field. Thus against his party’s inclinations but not his own better judgment, Polk sent the treaty to the Senate for its consideration. The Senate ratified the treaty on March 10, 1848.

The war that grew out of and made real Polk’s ambitions dramatically reshaped the nation’s geographic boundaries. But it also transformed antebellum political culture and made salient sectional fault lines. Quick to embrace and promote the expansionist impulse that both grew out of and shaped the national consciousness, Polk remained oblivious to the threat that the slavery extension issue posed to his party and the nation. Polk’s presidency, a recent biographer sighed, “suggested he didn’t always have the keenest awareness of where events were taking him.” More is the pity. But Ralph Waldo Emerson did. He predicted that a Mexican cession “will be as the man [who] swallows arsenic, which brings him down in turn. Mexico will poison us.”[14]

It already had.

- [1] Jackson believed that John Quincy Adams had wrongly given away Texas for other considerations from Spain in the Transcontinental Treaty in 1819. Jackson and others contended that it was part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Liberty, he maintained, was coeval with the boundaries of the United States. Texas was therefore integral to an American empire of liberty. See Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833-1845 (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 352.

- [2]Michael A. Morrison, Slavery and the American West: The Eclipse of Manifest Destiny and the Coming of the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 17.

- [3] William Robinson Watson, An Address to the People of Rhode Island, Published in the Providence Journal, in a Series of Articles during the Months of September and October, 1844 (Providence: Knowles and Vose, Printers, 1844), 5.

- [4] Van Buren letter, Washington Globe, April 27, 1844; Supporters of annexation insisted that John Quincy Adams had wrongly (some would hint traitorously) ceded the area that encompassed the Texas republic in the Adams-Onís treaty (1819) which established the southwest border between the United States and Mexico. Spain ceded this territory in 1821 when it granted Mexico its independence. Unable to establish a satisfactory border with Canada in the northwest, the United States jointly occupied the Oregon territory with Great Britain. Expansionists in 1844 were determined to make good on their shadowy claim to a boundary as far north as 54 degrees, 40 minutes.

- [5] Clay to Stephen Miller, July 1, 1844, and Clay to Thomas Peters & John M. Jackson, July 27, 1844, in Henry Clay, The Papers of Henry Clay, eds. James F. Hopkins et al (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1959-92), 10:78-79, 91.

- [6] Robert W. Merry, A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, The Mexican War, and the Conquest of the American Continent (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009), 131.

- [7] Amy S. Greenberg, A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico (New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2012), 79.

- [8] James D. Richardson, comp., A Compilation of the Messages and papers of the Presidents, 1789-1897, 10 vols. (Washington DC: Published by the Authority of Congress, 1896-99), 4:442.

- [9] Morrison, Slavery and the American West, 41.

- [10] Eric Foner, “The Wilmot Proviso Revisited,” Journal of American History 56 (1969): 267-79.

- [11] Oberlin (OH) Evangelist, October 28, 1846.

- [12] Morrison, Slavery and the American West, 81-2, Webster to Fletcher Webster, Aug. 6, 1846, in Daniel Webster, The letters of Daniel Webster, from Documents Owned Principally by the New Hampshire Historical Society, ed. Claude H. Van Tyne (New York: McClure, Phillips, 1902), 348.

- [13] The “immortal 14” were the handful of Whigs who voted against the war measure that passed by a 174-14 margin in the House of Representatives.

- [14] Merry, A Country of Vast Designs, 407; Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks, ed., William Gilman et al. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960-82), 9:430-31.

If you can read only one book:

Greenberg, Amy S. A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 Invasion of Mexico. New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2012.

Books:

Bauer, K. Jack. The Mexican War, 1846-1848. New York: Macmillan, 1974.

Blue, Frederick J. The Mexican War, 1846-1848. New York: Macmillan, 1974.

Brack, Gene M. No Taint of Compromise: Crusaders in Antislavery Politics. Baton Rouge. Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Clary, David A. Mexico Views Manifest Destiny, 1821-1846, An Essay on the Origins of the Mexican War. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1975.

DeVoto, Bernard. The Year of Decision: 1846. Boston: Little Brown, 1943.

Eisenhower, John S. D. So Far From God: The U.S. War with Mexico, 1846-1848. New York: Random House, 1989.

Foos, Paul. A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict During the Mexican-American War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Francaviglia, Richard V. and Douglas W. Richmond, eds. Dueling Eagles: Reinterpreting the U.S. Mexican War. Fort Worth: Texas A&M University Press, 2000.

Graebner, Norman A. Empire on the Pacific: A Study in American Continental Expansionism. New York: Ronald Press, 1955.

Henderson, Timothy J. A Glorious Defeat: Mexico and its War with the United States. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2008.

Hietala, Thomas R. Manifest Design: Anxious Aggrandizement in Late Jacksonian America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985.

Graebner, Norman A. Empire on the Pacific: A Study in American Continental Expansionism. New York: Ronald Press, 1955.

Henderson, Timothy J. A Glorious Defeat: Mexico and its War with the United States. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2008.

Hietala, Thomas R. Manifest Design: Anxious Aggrandizement in Late Jacksonian America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985.

Holt, Michael F. The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Horsman, Reginald. Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Anglo-Saxonism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.

Hyslop, Stephen G. Bound for Santa Fe: The Road to New Mexico and the American Conquest, 1806-1848. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002.

Johannsen, Robert W. To the Halls of the Montezumas: The Mexican War in the American Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Levinson, Irving W. Wars Within Wars: Mexican Guerrillas, Domestic Elites, and the United States of America, 1846-1848. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 2005.

McKivigan, John R. ed. Abolitionism and American Politics and Government. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Merk, Frederick, and Lois Bannister Merk. Manifest Destiny and Mission in American History: A Reinterpretation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963.

Merry, Robert W. A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, The Mexican War, and the Conquest of the American Continent. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009.

Morrison, Michael A. Slavery and the American West: The Eclipse of Manifest Destiny and the Coming of the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Olguin, B. V. “Sangre Mexicana/Corazon Americano: Identity, Ambiguity, and Critique in Mexican-American War Narratives,” in American Literary History 14.1 (Spring 2002): 83-114.

Pletcher, David M. The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1973.

Reséndez, Andrés. Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800-1850. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Reséndez, Andrés. Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800-1850. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Santoni, Pedro. Mexicans at Arms: Puro Federalists and the Politics of War, 1845-1848. Fort Worth: Texan Christian University Press, 1996.

Schroeder, John H. Mr. Polk’s War: American Opposition and Dissent, 1846-1848. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1973.

Sellers, Charles. James K. Polk: Continentalist, 1843-1846. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1966.

Stephanson, Anders. Manifest Destiny: American Expansionism and the Empire of Right. New York: Hill and Wang, 1995.

Stewart, James Brewer. “Reconsidering the Abolitionists in an Age of Fundamentalist Politics,” in Journal of the Early Republic 26 no.1 (Spring 2006):1-24.

Weinberg, Albert K. Manifest Destiny: A Study of Nationalist Expansionism in American History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1935.

Winders, Richard Bruce. Mr. Polk’s Army: The American Military Experience in the Mexican War. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1997.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.