The Mine Run Campaign

by James K. Bryant II

The Mine Run Campaign was Meade's last and failed attempt in 1863 to destroy Lee's Army of Northern Virginia before winter halted military operations.

Mine Run for a member of the 18th Massachusetts Infantry “was the hardest fought battle I ever experienced.” A soldier of the 1st North Carolina Infantry recorded that it had “been a very severe seven-days’ campaign, as we fought mostly all the time.”[1] Military operations in the four and a half months following Gettysburg were characterized by veterans of both the Federal Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia as “campaigns of maneuver.” While some thought the armies conducted military operations “like the moves in a game of chess,” others simply saw them playing “a very big game of Tag.”[2] Mine Run, a small stream “crooked as a snake track” according to one Confederate soldier, traversed the northern part of Orange County, Virginia, emptying into the Rapidan River. This seemingly insignificant tributary would lend its name to the last major military operation in central Virginia in 1863.[3]

Initiated by Major General George Gordon Meade commanding the Army of the Potomac, the Mine Run Campaign (November 26-December 2, 1863) would be his last attempt to conduct offensive operations against General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia before the impediments of winter halted his efforts. Under continuing pressure from the U.S. War Department to vigorously pursue and destroy Lee’s Confederates following the Gettysburg victory (July 1-4, 1863), Meade launched a series of reconnaissance operations in August and September hoping to fix the location of the Confederates south of the Rappahannock River. As the Federal commander maintained “a threatening attitude toward the enemy,” Lee had concentrated his army around Culpeper Court House between the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers. Significant portions of both armies were detached and sent to the Western Theater by the end of September 1863.[4]

Taking advantage of the transfer of enemy troops, Lee went on the offensive in early October on his “Bristoe Campaign” hoping to strike a decisive blow to the Federals while indirectly bolstering Confederate efforts in Tennessee. Meade conducted a retrograde movement across the Rappahannock River to Centreville in order to protect the right flank and rear of his army. The culminating fight at Bristoe Station on October 14, 1863 proved a disaster to the Confederates as they impetuously attacked the rear guard of Meade’s army suffering high casualties and the escape of the enemy. Lee, concerned over limited resources, withdrew back toward the Rappahannock destroying significant portions of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad (O&A) along the way. Lee’s withdrawal gave way to Meade’s advance across the Rappahannock River on November 7, 1863, resulting in the twin battles at Kelly’s Ford and Rappahannock Station. Meade’s victories at these places secured the Army of the Potomac’s position south of the Rappahannock forcing Lee to move south of the Rapidan River paving the way for the Mine Run Campaign.

Lee’s army, at a little more than 48,000 men, now occupied positions overlooking high bluffs along the upper Rapidan stretching close to 18 miles. The left flank rested near Liberty Mills with Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill’s Third Corps flung along northeasterly just past Rapidan Station that straddled the O&A to Robertson’s (Robinson’s) Ford. Lieutenant General Richard Stoddard Ewell’s Second Corps picked up Lee’s front from Robertson’s Ford facing northward across the river to Morton’s Ford. A portion of Ewell’s line was refused eastward near Morton’s Ford running parallel to Mine Run protecting the Confederate right flank. Orange Court House, a major stop on the O&A, was the nerve center for the Army of Northern Virginia. The O&A continuing to the southwest for another 9 miles reached Gordonsville where it intersected with the Virginia Central Railroad heading east to the Confederate capital at Richmond. This rail link was essential to Confederate supply and transportation needs. Additionally, Lee’s forces covered two of the major roads in the region—the Orange Turnpike and the Orange Plank Road—running eastward toward Fredericksburg quick movement for his army against Federal threats from that direction.[5]

Ascertaining the absence of a Confederate presence at the lower fords of the Rapidan, Meade believed he could turn Lee’s right flank quickly isolating and enveloping Ewell’s Corps before Hill could come up in support and “render more certain the success of the final struggle.” Meade’s chief of staff, Major General Andrew Atkinson Humphreys, later explained, “The commander of [the Army of the Potomac] can never forget that he is to protect Washington, as well as to carry on an offensive war.” Meade’s contemplated movement against Lee would not necessarily overtax his supply and communication lines while keeping the national capital safe placating his superiors.[6]

On the appointed day, November 24, in the Federal camps situated between Culpeper Court House and Rappahannock Station over 81,000 men were assembled, issued 10 days rations, and ordered to march by 7:00 a.m. Heavy rains halted the moving columns as they became mired in mud. One regimental surgeon upon his return to camp had to bail out his quarters “as one would bail out a leaky boat.” A reluctant Meade postponed the army’s advance for two days.[7]

Finally launching his campaign on November 26—Thanksgiving Day as proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln on October 3—the army got into motion. Many soldiers were undoubtedly unhappy with the interruption of planned festivities. Attempting to place a positive outlook on the army’s impending movement, an officer in the 14th Connecticut Infantry conferred the hope, “…[8][M]ay we at least be doing that which shall give the country some cause of lasting thanksgiving!” The day before, Meade had received the news of Major General Ulysses Simpson Grant’s victory over the Confederate forces of General Braxton Bragg at Chattanooga, Tennessee. This news was “to be announced to the [Army of the Potomac] troops in the morning before they marched” providing added motivation to the prospect of success.

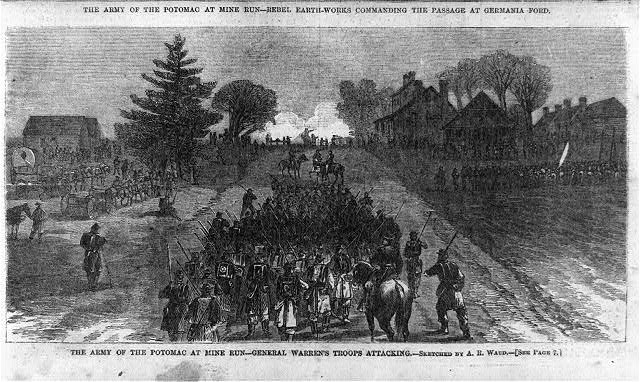

Meade crossed the Rapidan in three columns. The left column composed of the V Corps under Major General George Sykes followed by the I Corps under Major General John Newton crossed at Culpepper Mine Ford. The center column composed of the II Corps under Major General Gouverneur Kemble Warren crossed four and a half miles upriver at Germanna Ford. Warren’s objective was to take possession of the crossroads at Locust Grove (also known as Robertson’s Tavern) behind Confederate lines, but in close supporting distance to reinforce the right column. It was this right column that would deliver the “punch” into Lee’s right flank. Composed of the III Corps under Major General William Henry French followed by the VI Corps under Major General John Sedgwick, the column crossed at Jacob’s Ford about three and a half miles upriver from Germanna Ford. These two corps were the largest in the Army of the Potomac. If all went according to plan, the III Corps would eventually form a junction on the right of the II Corps near Locust Grove. Sedgwick’s VI Corps would act as reinforcement to the right column and additional support as needed once the Federals were concentrated. Two of the army’s three cavalry divisions covered the left and right flanks of the maneuver, while the third guarded the fords on the Rapidan.[9]

Meade’s battle plans were sound on paper. Unfortunately, his preparation did not account for the effects of poor weather, roads turned into mud-soaked lanes forcing artillery and supply trains on circuitous routes, shortages in bridging equipment delaying troop crossings over the Rapidan, and the difficulty of moving a large army through a unique terrain feature known locally as the “Wilderness.” This secondary-growth timber of scrub oak and dwarf pine occupying eastern Orange County harkened back to a minor iron industry that had operated in the region beginning in the eighteenth century. The Wilderness figured prominently during the Chancellorsville Campaign six months before and would be a major contributor to a future campaign six months after Mine Run. An army on the offensive had to negotiate through the Wilderness quickly before they encountered the enemy and Meade’s columns were already a day behind schedule.

Watchful scouts kept Lee apprised of Federal movements. Confirmation of the enemy’s crossing set the Confederate army in motion early on November 27. Still unsure if Meade sought to turn his right flank or make a move toward Richmond, Lee resolved “to strike the enemy while moving, or accept battle if offered.” Ewell’s Corps, under the temporary command of Major General Jubal Anderson Early, placed his three divisions on the march eastward to converge at Locust Grove on the Orange Turnpike. Hill’s Corps farther west pushed his three divisions along the Orange Plank Road. “After breaking camp our first intimation that a battle was expected was the invariable profusion of playing-cards along the road,” one of Early’s artillerymen keenly observed, “I never saw or heard of a Bible or prayer-book being cast aside at such time, but cards were always thrown away by soldiers going into battle.” [10]

The leading brigades of Early’s Division (under the command of Brigadier General Harry Thompson Hays) had hoped to secure a good position in one of the few clearings of the Wilderness at Locust Grove. Unfortunately, Federal skirmishers had already pushed past the crossroads at Locust Grove gaining possession of the open high ground beyond. Warren’s Federal II Corps had reached its initial destination by 10:00 a.m. Meade, accompanying this column, ordered Warren to push back the enemy skirmishers, but avoid a general engagement until French’s column arrived on Warren’s right flank in support. Likewise, Hays with the lead Confederate units without clear lines of sight for artillery and finding it “inexpedient to attack without co-operation” awaited the arrival of the Confederate division under Major General Robert Emmitt Rodes approaching to the left of his position. Rodes, made aware of Hays’s skirmishing, advised holding the position until the final third of the Confederate Second Corps—the infantry division under Major General Edward Johnson—arrived from the direction of the Raccoon Ford Road.[11]

Almost four miles south of Locust Grove, the Federal cavalry division under Brigadier General David McMurtrie Gregg had preceded Sykes’s infantry column to Parker’s Store on the Orange Plank Road. Traveling between the end of the V Corps column and the head of the I Corps was the V Corps supply and baggage train. Sometime during the late morning as the train began a right turn onto the Orange Plank Road at its intersection with the Brock Road, elements of Confederate cavalry (some disguised as Federal soldiers) under Brigadier General Thomas Lafayette Rosser attacked the train that had been left unguarded on its flanks. Federal units at the head of the I Corps fended off the raiders. One Wisconsin soldier arriving to the rescue witnessed the explosion of one of the ammunition wagons set on fire by the raiders. “Twas a pretty sight if it was our own,” he wrote. “The pieces flew & the shells burst in evry [sic] direction.” Among the confiscated items was the personal baggage of Brigadier General Joseph Jackson Bartlett who commanded a V Corps brigade. Meade, fuming over the apparent lack of adequate protection of the V Corps trains, channeled his anger onto Bartlett with the remark, “’I wish they had got away with all your personal baggage.’” Bartlett reportedly replied, “’They did so, general.’”[12]

By 9:00 a.m., the head of the V Corps column reached Gregg’s troopers at Parker’s Store. Gregg continued westward on the Orange Plank Road toward New Hope Church and ran into elements of the Confederate cavalry under the direct command of Lee’s cavalry chieftain, Major General James Ewell Brown Stuart, ahead of Hill’s Third Corps. Both sides dismounting due to the densely wooded landscape contested control of the rare clearing west of the church. The outnumbered Confederates soon found support from Hill’s leading infantry division under the command of Major General Henry Heth who deployed his men across the road pushing back the dismounted Federal cavalry skirmishers. By 3:00 p.m., Sykes began deploying his infantry in support of Gregg’s cavalry as “the engagement became very warm.”[13]

The heavy skirmishing at Locust Grove and New Hope Church revealed glaring gaps in the battle lines for both Meade and Lee. Although Warren reported being “in sight” of Sykes approaching on his left at 11:00 a.m., Meade ordered the I Corps that had followed the V Corps to break off near Parker’s Store and head toward Locust Grove to hold the area between Warren and Sykes. Lee likewise, hoping to shore up his own developing battle line cautioned Heth to ascertain the enemy strength and not bring on a general engagement until the rest of Hill’s Corps arrived in support.[14]

Meanwhile, Meade’s right column spearheaded by French’s III Corps—the linchpin of his operations—had fallen several hours behind the other two columns. In addition to the aforementioned difficulties in crossing the Rapidan, the III Corps contended with poor guides and indecision on the part of its leadership in locating proper routes in arriving at its expected destination. Time whittled away and French was more than three miles distant from Warren’s position. Meade sent several dispatches urging French to Locust Grove. Around 11:30 a.m., Meade’s headquarters received a dispatch from French sent two hours earlier indicating that he was near the Orange Turnpike and waiting for Warren. A perplexed and enraged Meade issued a reply through his chief of staff wondering why French was waiting for Warren who had been engaged with the enemy for over an hour. “[Warren] is waiting for you….move forward as rapidly as possible,…where your corps is wanted.”[15]

Since the late morning, French’s leading division as it traveled in a southerly direction on the road leading from Jacobs Ford had been skirmishing on their right flank with what they believed to be dismounted Confederate cavalry. In reality, it was enemy skirmishers of General Johnson’s infantry division guarding their own left flank as they marched southwestward toward Locust Grove to connect with Rodes’ division. Shortly past noon at the junction of these two roads, Federal skirmishers attacked the passing ambulance train near the rear of Johnson’s marching columns.

Brigadier General George Hume Steuart commanding a mixed brigade of North Carolina and Virginia troops guarding the rear of Johnson’s Division swung his men north to meet the enemy. It would not be long before Steuart’s men would discover that they were dealing with a large body of Federal infantry. They would hold the road intersection at all hazards. Johnson, who had reached Locust Grove at the head of his column and conferring with Generals Early and Rodes, heard the firing behind him on the Raccoon Ford Road. A messenger riding up to him confirmed that the rear of his division was under attack. Ordering his remaining three brigades to about face to the support of Steuart, Johnson sped back to the road junction. Johnson’s Division had counted 5,295 infantry the week before.[16]

Opposed to Steuart’s men was the III Corps division under Brigadier General Henry Prince who deployed his two brigades present into a line of battle across the Jacobs Ford Road. Since a third brigade under Prince remained behind at Jacobs Ford on picket duty, Prince probably had about 3,500 men on the field outnumbering Steuart’s men when they clashed in the thick and tangled woods. Brigadier General Joseph Bradford Carr commanding another III Corps division of about 5,000 men moved off of the Jacobs Ford Road and extended Prince’s line to the left following the contours of a wooded ridge creating an arc facing south to southeast. Johnson’s supporting brigades arriving on the scene fanned out skirmishers in the vicinity of Carr’s position. In between was a clearing occupied by two homesteads of the Payne Family giving the developing engagement its name—Payne’s Farm.[17]

Throughout the afternoon, Federal and Confederate lines surged back and forth as they repeatedly attempted to outflank each other. “We did not mind the artillery fire,” observed one Confederate combatant, “but the musket balls flew very thick.” Johnson’s brigades launched assaults against Federal positions unclear of enemy strength. “When the Rebs came down our flank they made a noise just like a flock of geese…demanding of us to surrender,” wrote a III Corps soldier, “but I could not see it.” Carr’s men running low on ammunition late in the afternoon were relieved in timely fashion by the III Corps division of Major General David Bell Birney. A brigade of Georgia troops from Rodes’ Division arrived in the early evening to bolster Johnson’s position as his men began running low on ammunition. Darkness brought a close to the Battle of Payne’s Farm. The Federals had 952 casualties when compared to the 545 for the Confederates. Many of the dead, dying, and wounded remained in the cold Wilderness that night although details from both sides made successful and unsuccessful attempts to recover fallen comrades.[18]

Realizing that further advancement was impossible against superior numbers, Lee fell back two miles behind the western bank of Mine Run under the cover of darkness. His men spent the night and early morning hours improving their defenses. “…[O]ur men entrenched as well as they could with almost no implements, using their bayonets, tin cups, and their hands, to loosen and scoop up the dirt, which was thrown on and around the trunks of old field pine trees,” recalled a Confederate officer.[19]

Meade’s plans were dashed when the Confederates were no longer in his front the next morning. The resulting Federal pursuit was hampered with heavy rain occupying much of the day. Once they discovered the Confederate position a few hundred yards before them it was found to be more formidable than they had assumed. Unwilling to give up the offensive, Meade late on the evening of November 28 upon Warren’s suggestion ordered him to take his II Corps on a reconnaissance on the Confederate right near New Hope Church where it was suspected that the enemy lines were vulnerable. Reinforced by a division from the VI Corps, additional artillery batteries, and a small contingent of cavalry, Warren was tasked with flanking Lee’s position forcing him to abandon his defensive works. Meade’s other corps commanders as they shuffled troops studied the Confederate positions in their front seeking potential points to exploit to their advantage.[20]

Lee that same evening sent Stuart with a portion of his cavalry out on the Plank Road toward Parker’s Store to ascertain the extent of the Federal line as well as enemy intentions and to develop any opportunity to go on the offensive. A brief cavalry engagement at Parker’s Store between Stuart and portions of Gregg’s cavalry provided the intelligence that Warren’s reinforced column was on its way threatening the Confederate right flank.

On the afternoon of November 29, after an eight mile march Warren’s troops reached the area around New Hope Church that had been held by Sykes’s V Corps two days before. Deploying his troops beyond Mine Run where he discovered the Confederate positions lightly defended, Warren prepared for an assault. Dated reports of Confederate cavalry at Parker’s Store in his rear that alerted his presence to the enemy as well as the waning daylight, compelled Warren to suspend his movement. Later that evening, Warren arrived at Meade’s headquarters reporting on what he believed to be weaknesses of the Confederate defenses on their right flank.

Meade had already contemplated a general attack against the entire Confederate line, but Warren’s report caused the Federal commander to alter his plans accordingly. Attacks would be made on both the Confederate left and right flanks. Warren, assaulting on the enemy’s right, was reinforced with two divisions of French’s III corps giving him about 28,000 troops under his direct control. Sedgwick would direct both his own VI Corps and Sykes’s V Corps in an assault on the enemy’s left flank. Newton’s I Corps and the remaining division of the III Corps would feint an assault on the Confederate’s center and push forward as either flank assaults gained ground. The time was set for Sedgwick’s artillery to begin firing at the enemy works at 8:00 a.m. on November 30 followed by Warren’s attack on the Confederate right. Sedgwick’s assault on the Confederate left would take place at 9:00 a.m.[21]

The Confederates, anticipating a Federal assault, continued strengthening their positions behind Mine Run. A soldier in Heth’s Division was “anxious for the enemy to attack us.” Likewise, a member of the 3rd Richmond Howitzers hoped that Meade would find a Gettysburg in reverse asserting, “We are on our own ground, and Lee knows it well. God grant it may be victory to us, and that it may tend greatly towards the settling of this dreadful war.” Lee and his subordinate generals worked hard to influence “their eagerness for a fight” by remaining a constant presence on the front lines encouraging their troops as they labored on defensive works.[22]

It was a long and sleepless night for the Federal soldiers. If the extremely cold temperatures were not enough to try their resolve, the reality of a “desperate encounter” was heavy on their minds. Warren’s command would have to negotiate a broad marsh and other obstacles while crossing Mine Run before confronting the formidable enemy works. By the time the enemy works were reached in a frontal assault, enfilading fire from the mounted batteries would wreak heavy casualties on the Federals. “..[N]ot fear or a disposition to falter—but that they saw the situation and bravely prepared to do their duty and to die as became soldiers,” reflected the commander of the 8th Ohio Infantry as he prepared for the next day’s action. In addition to pinning strips of paper to their uniforms for later identification, the Army of the Potomac’s veterans took great pains to get their affairs in order. Army chaplains had the solemn duty of collecting personal items of soldiers to be forwarded to loved ones at home in the event that they did not survive the assault. Even Warren felt the pressure of his role in the unfolding drama. “If I succeed to-day I shall be the greatest man in the army; if I don’t, all my sins will be remembered,” he shared with his staff officers in the hours before the scheduled attack.[23]

The approach of dawn found the Army of Northern Virginia bracing for a major attack on their lines. Warren made a final inspection of the route of attack for his troops just prior to the scheduled artillery barrage on the opposite end of the Federal lines about four miles away. The reinforced earthworks and obstructions placed by the enemy to slow down advancing troops convinced him that an attack would be futile. Warren concluded “…[W]e would be exposed to every species of fire.” On his own initiative, he suspended his assault on the Confederate right and sent a staff officer to inform Meade of his action.[24]

Meanwhile, Sedgwick opened up his artillery on the Confederate left at 8:00 a.m. Meade waiting to hear small arms fire from Warren’s position on the right received the dispatch from Warren. Stunned at his subordinate’s action, Meade exclaimed, “’My God!...General Warren has half my army at his disposition!’” Meade ordered all firing from the Federal line to cease and rode to Warren’s position where the two had a “long consultation.” Observers would characterize this meeting as a heated exchange at times. After personally inspecting the lines on the Confederate right and eventually convinced by Warren’s arguments against an attack, Meade halted army operations. The lack of viable options to renew the offensive, dwindling supplies, and poor weather resulting in bad roads forced Meade to abandon his campaign and return to their camps across the Rapidan. Orders were issued for the army to begin its withdrawal on the evening of December 1. [25]

The commander of the Army of the Potomac shouldered the responsibility of what was not accomplished during his movement in spite of French’s tardiness on November 27 and Warren’s unilateral suspension of his attack on November 30. He concluded in his final report of the campaign:

Considering how sacred is the trust of the lives of the brave men under my command, but willing as I am to shed their blood and my own where duty requires, and my judgment dictates that the sacrifice will not be in vain, I cannot be a party to a wanton slaughter of my troops for any mere personal end.[26]

His conscious was clear. “All honor to General Meade,” wrote a Wisconsin officer, “who at risk of personal discomfiture, and at sacrifice of personal pride, had the moral courage to order a retreat without a day of blood and National humiliation.”[27]

Lee and his army continued waiting for the attack they believed was coming from Meade’s legions. The Confederates had returned artillery fire when Sedgwick’s cannon began their initial barrage and exchanged sporadic skirmish fire throughout November 30 and December 1. After two days, Lee decided to go on the offensive in light of the enemy’s apparent inactivity. Two divisions of A. P. Hill’s Third Corps under Major Generals Richard Heron Anderson and Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox were pulled out of the Confederate line early morning on December 2 to make an attack on the Federal left flank in the vicinity of the Plank Road. “…[A]s soon as it became light enough to distinguish objects, [Meade’s] pickets were found to have disappeared,” Lee reported to Richmond, “and on advancing our skirmishers it was discovered that [Meade’s] whole army had retreated under cover of the night.” Due to the dense woods, the Confederates proceeded cautiously and only succeeded in capturing straggling Federal soldiers who could not keep up with their comrades. “I am too old to command this army,” a frustrated Lee said to his staff, “we should never have permitted these people to get away.”[28]

Frustration was not limited to the Confederates. “Never since I enlisted have I been so discouraged as I am today,” wrote a soldier in the 19th Massachusetts Infantry. “Here we are marching from one end of Virginia to the other, wearing ourselves out and yet nothing seems to be accomplished by it.” Echoing similar sentiments that the wasted time and energy of the campaign brought no appreciable advantage, a Maine soldier remembered a regimental band posted on the north side of the Culpeper Mine Ford playing “’Oh! Ain’t’ you glad to get out of the Wilderness!’” as he and his comrades crossed the Rapidan on their return to camp. [29]

Some of the Federal veterans tried to paint a better picture of the situation. “I do not understand the late movements,” Lieutenant Elisha Hunt Rhodes of the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry who was to have participated in Warren’s attack, “but I presume Gen. Meade does and that is sufficient for me.” Lieutenant Charles Harvey Brewster, who like Rhodes escaped being a potential casualty on the Confederate right, took politicians, the press, and the general public in the North to task for their criticisms of Meade’s withdrawal. Referencing the ill-fated “Mud March Campaign” (January 20-23, 1863) of Major General Ambrose Everett Burnside following his defeat at Fredericksburg almost a year before, Brewster commented, “I wish some of the grumblers had been with us over there and had to stand in line of battle in drenching rain storms, and bitter cold nights possibly they would not be as anxious to fight as they are in [their] comfortable houses at home.”[30]

Others in the Army of the Potomac praised their leaders for what they believed was the appropriate decision. A member of the 102nd Pennsylvania Infantry reasoned that if the assaults contemplated for November 29 had succeeded, the victory would “have been barren of results” and could not be sustained since the army would have to fall back upon its base of supplies. Additionally, the victory would cost at least 20,000 in killed and wounded with half the projected wounded eventually dying of exposure to the cold elements. A group of soldiers of the 1st Delaware Infantry told their chaplain, “’We may thank General Warren for our lives to-night’” as they believed their entire unit would have been annihilated. Similar praises to the II Corps commander confirmed the idea that “[t]here was to be no more unnecessary slaughtering.”[31]

The Mine Run Campaign for one New York officer “had the virtue of being an honest effort to do something.” Even with disappointment, the soldiers in the Army of the Potomac resolved to see the end of the war with a Federal victory. The blue ranks had gained enough experience by the war’s third year to understand that ultimate victory would be a long and arduous journey. Soldiers remained committed to the preservation of the Union unhampered by growing northern opposition to the war as national elections loomed in the coming year.[32]

Lee hoped that antiwar opposition on the northern home front might influence northern policies and ultimately northern elections benefitting the Confederate war effort. It was crucial that the Army of Northern Virginia remained a threatening presence. “There is no way for the Yankees to win the war,” a Mississippi soldier entered into his journal after Mine Run. “Surely Lincoln can see this…men have died and are dying because the North is too stubborn to recognize the truth.”[33]

The one truth that both George G. Meade or Robert E. Lee recognized after Gettysburg was that they could not lose a decisive battle before the end of the year. Neither commander was willing to risk a defeat in Virginia that might turn the tide of military operations in the Western Theater of the war to their detriment. The campaigns of “missed opportunities” often characterized by modern scholarship would in reality be efforts to create opportunities that could help the respective war efforts of the antagonists. The Mine Run Campaign was one of these opportunities. If the war was not to be won in Virginia, Lee and Meade would make sure that it would not be lost in Virginia.

- [1] Thomas H. Mann, Fighting with the Eighteenth Massachusetts: The Civil War Memoir of Thomas H. Mann, ed. John J. Hennessy (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 223; Louis Leon, Diary of a Tar Heel Confederate Soldier (Charlotte, NC: Stone Publishing, 1913), 54.

- [2] John W. Chase, Yours for the Union: The Civil War Letters of John W. Chase, First Massachusetts Light Artillery, eds. John S. Collier and Bonnie B. Collier (Bronx, NY: Fordham University Press, 2004), 300; and Augustus Meyers, Ten Years in the Ranks U.S. Army (New York: Stirling Press, 1914), 303.

- [3] George M. Neese, Three Years in the Confederate Horse Artillery (New York: Neale Publishing, 1911), 241.

- [4] George G. Meade to Lorenzo Thomas, December 6, 1863, in United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 29, part 1, p. 9 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 9).

- [5] Lee’s numbers are derived from those listed as “Present for duty” on the returns available prior to Mine Run. Abstract from field return of the Army of Northern Virginia, November 20 [,1863]; Geo. G. Meade to Lorenzo Thomas, December 7, 1863; J.A. Early to W.H. Taylor, April 4, 1864, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 13, 823, 830-1.

- [6] Geo. G. Meade to Lorenzo Thomas, December 7, 1863, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 13; and “Testimony of Major General Andrew A. Humphreys, March 21, 1864,” in Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, H.R. Rep. No. 38(2) (1865) part 3, “Army of the Potomac”, 402 (hereafter cited as RJCCW).

- [7] [John Gardner Perry,] Letters from a Surgeon of the Civil War (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1906), 130-1.

- [8] [Samuel Wheelock Fiske,] Mr. Dunn Browne’s Experiences in the Army (Boston, MA: Nichols and Noyes, 1866), 325; S. Williams to [Gouverneur K.] Warren, November 25, 1863, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 2, 488.

- [9] Geo. G. Meade to Lorenzo Thomas, December 7, 1863, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 13-14.

- [10] R. E. Lee to S. Cooper, December 2, 1863, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 825; and Edward A. Moore, The Story of a Cannoneer Under Stonewall Jackson (New York: Neale Publishing, 1907), 212.

- [11] Harry T. Hays to G. Campbell Brown, January 22, 1864, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 839.

- [12] Rosser claimed the capture or destruction of 35-40 wagons, 8 loaded ordnance stores, 7 ambulances, 230 horses and mules, and 95 Federal prisoners. His only reported casualties were 2 men killed and 3 wounded. Federal estimates of losses in this brief raid were reported as 5 to 20 wagons with 8 or 9 casualties. Eugene Arus Nash, A History of the Forty-fourth Regiment New York Infantry in the Civil War, 1861-1865 (Chicago, IL: R.R. Donnelley and Sons, 1911), 174; L. Cutler to C. Kingsbury, Jr., December 3, 1863, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 689-690; William Ray, Four Years with the Iron Brigade: The Civil War Journal of William Ray, Company F, Seventh Wisconsin Volunteers, eds. Lance Herdegen and Sherry Murphy (New York: Da Capo Press, 2002), 238; Rufus R. Dawes, Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (Marietta, OH: E. R. Alderman and Sons, 1890), 224-5; George Baylor, Bull Run to Bull Run; or, Four Years in the Army of Northern Virginia (Richmond, VA: R. F. Johnson Publishing, 1900), 180-181; Thomas L. Rosser to T. G. Barker, December 7, 1863, in OR, I, 29, pt. 1, 904; Edwin C. Bennett, Musket and Sword, or the Camp, March, and Firing Line in the Army of the Potomac (Boston, MA: Coburn Publishing , 1900), 169-170; and John L. Parker, History of the Twenty-second Massachusetts Infantry, the Second Company Sharpshooters, and the Third Light Battery in the War of the Rebellion (Boston, MA: Rand Avery, 1874), 383.

- [13] George Sykes to A. A. Humphreys, December 4, 1863, in OR, I, 29, pt. 1, 794.

- [14] G. K. Warren to [Humphreys], November 27, 1863-11 a.m., in OR, I, 29, pt. 2, 499; and John Newton to S. Williams, December 3, 1863, in OR, I, 29, pt. 1, 687.

- [15]A. A. Humphreys to [William H.] French, November 27, 1863-11:30 a.m., in O.R., I, 29, pt. 2, 500.

- [16] Johnson’s Division was composed of the following infantry and supporting units (in the order of march to Locust Grove on November 27, 1863): Brigadier General John M. Jones’s Brigade (Virginia troops); Brigadier General Leroy A. Stafford’s Brigade (Louisiana Troops); Brigadier General James A. Walker’s ‘Stonewall” Brigade (Virginia troops); Lieutenant Colonel Richard S. Andrews’s Artillery Battalion (Virginia/Maryland gun crews-16 guns); division ambulance train; Brigadier General George H. Steuart’s Brigade (Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia troops). Andrews’s battalion possibly added 300 more men to the division, but the majority of the guns would remain parked near the intersection due to the difficulty of the terrain to be of much use. Abstract from field return of the Army of Northern Virginia, November 20 [1863], in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 13, 823.

- [17] Prince’s two brigades present were under the command of Colonel William Blaisdell and Colonel William R. Brewster. The 73rd New York Infantry of Brewster’s brigade was detached guarding the III Corps trains further reducing Prince’s Division strength at Payne’s Farm. The detached third brigade was led by Brigadier General Gershom Mott. Carr’s division was organized in three brigades under Brigadier General William H. Morris, Colonel J. Warren Keifer, and Colonel Benjamin F. Smith. Smith’s brigade having difficulty maneuvering through the wooded terrain found itself on the other side of a small creek known as Russell Run separated from the rest of the division for much of the battle.

- [18] McHenry Howard, Recollections of a Maryland Confederate Soldier and Staff Officer Under Johnson, Jackson and Lee (Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins, 1914), 242; Bark Cooper, “Letter from the Army of the Potomac,” Belmont Chronicle (St. Clairsville, OH), December 17, 1863, 2; Geo. G. Meade, List of Casualties during the recent operations of the Army of the Potomac, November 26-December 4, 1863, December 13, 1863; Wm. H. French, List of Casualties in the Third Corps during operations November 26-December 2, n.d.; and E. Johnson to G. Campbell Brown, February 2, 1864, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 20, 746, 847.

- [19] Howard, Recollections of a Maryland Confederate Soldier, 243.

- [20] Warren later testified that he had 10,000 men in his corps (the smallest in the Army of the Potomac). The returns for November 20, 1863 have the II Corps with a present for duty strength of 10,936. Brigadier General Henry D. Terry commanded the VI Corps division reinforcing Warren with 6,000 men. A force of 300 cavalry and additional artillery increased Warren’s command to about 18,000 for the reconnaissance. “Testimony of Major General G. K. Warren, March 10, 1864,” in RJCCW, 385; G. K. Warren to S. Williams, December 3, 1863, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 697-698; and also see Wm. H. French to A. A. Humphreys, December 4, 1863, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 740.

- [21] Brigadier Generals Henry Prince and Joseph B. Carr commanded the two III Corps divisions augmenting Warren’s assault column. While Warren three months later claimed he commanded 26,000 troops for the contemplated assault on November 30, French reported two days after the campaign that Warren had 28,000. Both divisions had about 5,000 soldiers each and consistent with the overall III Corps strength for the campaign. “Testimony of Major General G. K. Warren, March 10, 1864,” in RJCCW, 386; and Wm. H. French to A. A. Humphreys, December 4, 1863, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 740.

- [22] John A. Sloan, Reminiscences of the Guilford Grays (Washington, DC: R. O. Polkinhorn, 1883), 75; William S. White, A Diary of the War or What I Saw of It, No. 2, Contributions to a History of the Richmond Howitzer Battalion (Richmond, VA: Carlton McCarthy, 1883), 235; and William T. Poague, Gunner With Stonewall: Reminiscences of William Thomas Poague, ed. Monroe F. Cockrell (Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing, 1987), 81.

- [23] Franklin Sawyer, A Military History of the 8th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry: It’s Battles, Marches and Army Movements (Cleveland, OH: Fairbanks, 1881), 151-2; and Thomas L. Livermore, Days and Events, 1860-1866 (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1920), 301.

- [24] G. K. Warren to S. Williams, December 3, 1863 in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 698.

- [25] Geo. G. Meade to [Henry W.] Halleck, December 2, 1863—12 [am] in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 12; and Theodore Lyman, Meade’s Headquarters, 1863-1865: Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman From the Wilderness to Appomattox, ed. George R. Agassiz (Boston, MA: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1922), 56-7.

- [26] Geo. G. Meade to Lorenzo Thomas, December 7, 1863, in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 18.

- [27] Rufus R. Dawes, Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (Marietta, OH: E. R. Alderman and Sons, 1890), 230-231.

- [28] R. E. Lee to S. Cooper, December 3, 1863 and April 27, 1864 in O.R., I, 29, pt. 1, 826, 829; and Charles S. Venable, “General Lee in the Wilderness Campaign,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. 4, eds. Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel (New York: The Century Company, 1884, 1888), 240.

- [29] John Day Smith, The History of the Nineteenth Regiment of Maine Volunteer Infantry, 1862-1865 (Minneapolis, MN: Great Western Publishing, 1909), 120-121; History of the Nineteenth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1865 (Salem, MA: Salem Press, 1906), 281.

- [30] Elisha Hunt Rhodes, All for the Union: The Civil War Diary and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes (New York: Vintage Books, 1992), 127; and Charles Harvey Brewster, When This Cruel War Is Over: The Civil War Letters of Charles Harvey Brewster, ed. David W. Blight (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009), 269.

- [31] A.M. Stewart, Camp, March and Battlefield; or Three Years and a Half with the Army of the Potomac (Philadelphia, PA: James B. Rodgers, 1865), 366; Thomas G. Murphey, Four Years in the War: The History of the First Regiment of Delaware Veteran Volunteers (Philadelphia, PA: James S. Claxton, 1866), 144; and William Keppler, History of the Three Months’ and Three Years’ Service of the Fourth Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry in the War for the Union (Cleveland, OH: Leader Printing, 1886), 150.

- [32] Gilbert Frederick, The Story of a Regiment Being a Record of the Military Services of the Fifty-Seventh New York State Volunteer Infantry in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865 (The Fifty-Seventh Veteran Association, 1895), 206.

- [33] Austin C. Dobbins [and Franklin L. Riley], Grandfather’s Journal: Company B, Sixteenth Mississippi Infantry Volunteers, Harris’ Brigade, Mahone’s Division, Hill’s Corps, A.N.V., May 27, 1861-July 15, 1865 (Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1988), 174.

If you can read only one book:

Graham, Martin F. & George F. Skoch. Mine Run: A Campaign of Lost Opportunities, October 21, 1863-May 1, 1864. Lynchburg, VA: H.E. Howard, 1987.

Books:

United States War Department. War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 29, p. 11-20, 663-908.

Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, H.R. Rep. No. 38(2) (1865) part 3, Army of the Potomac, 295-524.

Gottfried, Bradley M. The Maps of the Bristoe Station and Mine Run Campaigns. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 118-63.

Luvaas, Jay and Wilbur S. Nye. “The Campaign That History Forgot,” in Civil War Times Illustrated, vol. 8 (November 1969): 11-42.

Neul, Robert C. “Double Missed Opportunity” in America’s Civil War, vol. 6 (March 1993): 26-32.

Savas, Theodore P. “’The Musket Balls Flew Very Thick’: Holding the Line at Payne’s Farm,” in Civil War, vol. 10 (May-June 1992): 20-3, 53-6.

Organizations:

Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park Virginia

Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park operated by the National Parks Service, preserves the American Civil War battlefields of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Mine Run Campaign. Brochures guiding visitors for the Mine Run battlefield are available at the Fredericksburg Battlefield Visitors Center, 1013 Lafayette Boulevard, Fredericksburg, VA 22401. Operating hours vary by season and can be obtained by calling 540373 6122 or 540 786 2880. The Park’s material on The Mine Run Campaign is available on line

Web Resources:

This is the Civil War Trust’s map of the Battle of Payne’s Farm (Mine Run Campaign)-November 27, 1863.

The Civil War Trust announced the opening in 2011 of Payne’s Farm Walking Trail.

The Civil War Trust’s Mine Run page includes a summary of the battle and useful links to related resources.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.