The Stonewall Brigade

by Richard G. Williams, Jr.

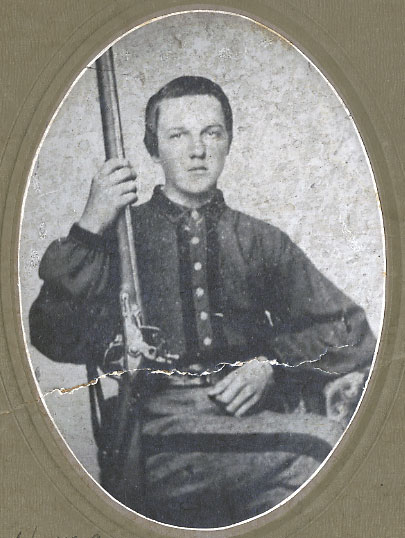

Sixteen year old Confederate soldier J. Triplett at Winchester VA. He served in the Stonewall Brigade and his family was from the Mt. Jackson area of the Shenandoah Valley. "His uniform was made for him by his mother."

“And men will tell their children,

Tho’ all other memories fade,

How they fought with Stonewall Jackson

In the old Stonewall Brigade.”[1]

The story of Confederate Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan Jackson’s now famous “Stonewall Brigade” has become almost mythical in its popular memory. Just mentioning the famous Confederate unit will summon up images of Jackson astride his almost as equally famous mount, Little Sorrel: his back gun barrel straight, jaw set, and his steel blue eyes fixated on the battle raging before him. This elite unit has been compared to Charlemagne’s Paladins, Caesar’s Tenth Legion, and Napoleon’s Old Guard.

But little did the Virginia men assembling at Harper’s Ferry in April of 1861 know that their service under the command of then Major T.J. Jackson was to become legendary in the annals of military history. Those present at that first assembly hardly looked to have the makings of a legend. Though not much more than a rag-tag bunch of undisciplined plow boys, common laborers, students, merchants, and tradesman, Jackson would soon whip the naïve volunteers into the most feared and respected fighting machine in the Confederacy.

James I. Robertson, Jr. described the genesis of this unit after Virginia voted for secession on 17 April 1861: “Out of the Valley came hundreds of men to answer their state’s call. From them were formed five regiments and a battery of artillery which were designated as the First Brigade, Virginia Volunteers. Within the regiments were forty-nine companies, each with a letter and distinctive nickname. The Second and Thirty-third Regiments originated in the lower (northern) end of the Valley, in the area around Harrisonburg, Winchester, and Charlestown. The Fourth Regiment came from the upper (southern) end of the Valley, and included companies from Pulaski, Marion, Bristol, Wytheville, and as far down the Valley as Lexington. The Staunton and Augusta County area, midway in the Valley, provided the nucleus for the Fifth Regiment, the largest unit in the brigade. The smallest regiment, the Twenty-seventh, was composed of men from the Lexington area and the counties to the west. Actually, the Twenty-seventh was more a battalion than a regiment, since it lacked a full complement of ten companies. Associated with the Stonewall Brigade until latter part of 1862, was the Rockbridge Artillery. This Lexington battery was commanded initially by an Episcopal rector, William Nelson Pendleton, who later became chief of Lee’s artillery.”[2]

The various companies within the brigade were as diverse in personality and temperament as were the individual men that formed them. Since many of these men hailed from the Shenandoah Valley, a large number of them were of Scots-Irish and Irish ancestry. Evidence of this consistent pedigree was apparent in the “Emerald Guards,” Company E, Thirty-Third Virginia. Every man in this unit was Irish and worked and lived as common laborers in the New Market area. Many of these men signed an “X” on muster documents, lending evidence to the fact that they were largely illiterate and unable to even sign their own name. Jackson considered the company the “problem child” of the Stonewall Brigade due to its partiality for “liquor and brawling.”[3] One historian aptly described their irreligious proclivities: “. . . the Sons of Erin did not mesh easily with their conservative neighbors, most of whom were of German and Scotch-Irish descent. The Celts' predilection for hard liquor and their affinity for world-class brawling at the least provocation engendered a definite air of notoriety.”[4] Many in Company E undoubtedly joined in the South’s struggle for the pure joy they would receive from fighting.

Another company within the brigade enjoyed a more pious reputation and would be considered among those “conservative neighbors” with whom the Sons of Erin did not easily mesh. Company I, Fourth Virginia, the “Liberty Hall Volunteers”[5] was comprised primarily of students from Washington College in Lexington. All the officers, as well as more than half the privates, were professing Christians, and one-fourth were candidates for the ministry. Upon their flag was emblazoned the Latin phrase “Pro Aris et Focis” - the English translation being simply “For Altar and Home.” The company was organized and commanded by James J. White, professor of Greek at Washington College and son of Stonewall Jackson's pastor, the Reverend William S. White.

Perhaps motivated by a “higher calling” than their Irish cousins, their flag’s motto revealed that these young men saw the conflict as a religious crusade - repelling those who would desecrate what they viewed as holy. Hugh White, the younger brother of Captain James White, seemed to express these sentiments in a letter to his father on April 22, 1861: “We of Virginia are between two fires. If we join the one party, we join friends and allies; if we join the other, we join enemies and become vassals. Our decision then is formed, and we will seek to break the oppressor's yoke. Our only hope, under God, is in a united resistance even unto death . . .”[6] And, in further contrast to the Emerald Guards, the Liberty Hall Volunteers were one of the best educated infantry units in the Confederate army.

Despite the diversity of backgrounds when comparing these two companies, there was also a unique cohesiveness within the ranks of the Stonewall Brigade. Much of this would come through the shared baptism of battle, along with the shared glory of numerous victories against an often numerically superior and better equipped enemy. But some of this bond was familial. James Robertson makes special note of this aspect of the brigade: “One characteristic of the Stonewall Brigade deserves special mention. To a large extent this unit was a family affair, or, as one historian has termed it, a “cousinwealth.” So many families contributed such a large number of sons, cousins, and other close relatives that the muster rolls at times read like genealogical tables.”[7]

Brawlers and preachers, farmers and students, cousins and neighbors, as different as they were alike, the core of these men all came to have one thing in common: a belief that, under Jackson’s command, they were invincible. And their reputation of invincibility often preceded them. Historian Robert K. Krick describes what the Stonewall Brigade’s presence and reputation engendered at the Battle of Chancellorsville: “The spectral image of Stonewall Jackson heightened the impact."Jackson was on us," an Ohio soldier wrote, "and fear was on us." A colonel from Massachusetts drolly described his fleeing friends as "under the influence of an aversion for Stonewall Jackson." Terrified Yankees "ran some one way and some another." In frightened attempts to hide, a North Carolinian wrote, "some of them ran in the tent and wrapped up in blankets." Captain J. W. Williams of Greensboro, Alabama, described "a moving mass of yankees hundreds would turn and run to us to be taken prisoners." A Northern band must have been among the last to learn of the disaster: their boisterous tooting and thumping covered the noise of the initial onslaught, until a bullet shattered the bass drum. Disintegration spread inexorably eastward. A French volunteer at Hooker's headquarters spotted the XI Corps fugitives in "close-packed ranks rushing like legions of the damned" toward him. The Rebel yell unmanned the foreigner, who reported that "all of the [Confederates] roar like beasts.”” [8]

That roar was first heard at the Battle of Manassas. It was in the shadows of the Federal capital where Jackson earned the sobriquet, “Stonewall.” But Jackson was quick to point out that it was his men, and not he who deserved any laurels, once stating that, “the name Stonewall ought to be attached wholly to the men of the brigade . . . for it was their steadfast heroism which had earned it at first Manassas.” [9]

Though the Stonewall Brigade gained immortality through its dramatic battlefield successes and association with Jackson, it was not without its problems. Desertions, stragglers, and drunkenness were, as with other units, difficulties with which Jackson and his officers had to deal. The way in which Jackson dealt with some of these problems has been the subject of criticism, particularly Jackson’s ordered executions of deserters. Jackson saw such actions as necessary for maintaining discipline and e protection for the rest of the army, a sentiment expressed by one of his aides’ opinion of such measures: “the preservation of the army itself was dependent on the maintenance of discipline, and discipline could not be had if desertions were longer to go unpunished.” Wanting to impress the consequences of desertion upon the rest of his men, Jackson once ordered officers to march their regiments by the executed men’s bodies lying in their exposed graves. [10] Other, less severe punishments such as flogging and “labor with ball and chain” were also employed. [11]

Though there was often grumbling within the ranks over Jackson’s strict adherence to military code and conduct, when coupled with Jackson’s courage, bravery, and willingness to suffer the same hardships as his men, it also had positive effects. Most men of the Stonewall Brigade were fiercely loyal to their commander and held him in high esteem. James Robertson explains: “A mutual confidence between commander and commanded is one of the secrets of the success enjoyed by Jackson and his Stonewall Brigade. The men were so devoted to him that they would attempt the impossible if he requested it. “I do not think,” a captain in the Fifth Regiment wrote his father in 1862, “that any man can take General Jackson’s place in the confidence and love of his troops . . .””

Such feelings were not confined to private correspondence. Robertson continues:

“Jackson’s men cheered him whenever they saw him, even on the secret marches for which he became famous. Where the brigade was concerned, Jackson often found it necessary to conceal himself, lest their shouts divulge their presence to the Federals.” [12]

And while Jackson was reputedly concealed his emotions to others, the mutual admiration he held for his “Foot Soldiers” sometimes became quite evident. In part of his now famous speech given upon the occasion of his promotion to Major General, Jackson betrayed his fondness for the men who had fought so valiantly and sacrificed so much under his command: “In the Army of the Shenandoah, you were the First Brigade! In the Army of the Potomac you were the First Brigade! In the Second Corps of this army you were the First Brigade! You are the First Brigade in the affections of your general, and I hope by your future deeds and bearing you will be handed down to posterity as the First Brigade in this, our second War of Independence. Farewell!” [13]

Jackson’s words on that particular day were prophetic. Remnants of the Stonewall Brigade continued to function as the 116th Infantry Regiment of the Virginia National Guard seeing heavy action in France, and in just over two months of combat, the unit suffered 1,000 casualties. The unit’s reputation was once again recognized - and honored - when it was chosen as the only National Guard unit to be included in the first wave of invasion forces on D-Day. According to author and Brigadier General Theodore G. Shuey, Jr., the decision was a conscious one made by General George C. Marshall. The order had two motivations: to honor Marshall’s alma mater as well as Jackson’s legacy, and to send the message to Hitler that America’s citizen soldiers were well up to the task of defeating the Nazis. [14]

From Manassas in 1861, to the brilliantly executed Valley Campaign of 1862, to Jackson’s mortal wounding at Chancellorsville, to the final surrender at Appomattox, the story of the Stonewall Brigade will forever be immortalized for their service to Virginia and their nation, and men will continue to share their story with their children.

- [1] John Esten Cooke, From “The Song of The Rebel,” Stonewall Jackson and the Old Stonewall Brigade (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1954), 3.

- [2] James I. Robertson, Jr., The Stonewall Brigade (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963), 10-11.

- [3] Robertson, 13.

- [4] Lowell Reidenbaugh, 33rd Virginia Infantry (Lynchburg, Virginia: H.E Howard, Inc., 1987), 2.

- [5] These young men chose this name which was also used by a similar company of youths formed at the original Liberty Hall Academy—the forerunner of Washington College. The original company marched with William Graham to repel a British invasion on the east side of the Blue Ridge Mountains during the American Revolution. On June 13, 1861, the Lexington Gazette described the unit as “one of the finest looking bodies of young soldiers that have been sent from this portion of the state. ... The patriotic fire which animated the breasts of the boys of Liberty Hall in the days of our Revolutionary struggle is still alive in the hearts of their worthy descendants.”

- [6] William S. White, Sketches of the Life of Captain Hugh A. White of the Stonewall Brigade by His Father (Harrisonburg, Virginia: Sprinkle Publications, 1997), 44-45. (Reprint, originally published in 1862)

- [7] Robertson, 21.

- [8] Robert Krick, “Like Chaff Before the Wind': Stonewall Jackson's Mighty Flank Attack at Chancellorsville”(N.p., N.d.), accessed 27 March 2012, http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/chancellorsville/chancellorsville-history-articles/flankattackkrick.html

- [9] William W. Bennett, A Narrative of the Great Revival Which Prevailed in the Southern Armies During the Late Civil War Between the States of the Federal Union (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Claxton, Remsen & Haffelinger, 1877), 297.

- [10] Thomas W. Cutrer, “Military Executions During the Civil War.” 5 April 2011, accessed 27 March 2012, Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. <http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Military_Executions_During_the_Civil_War>.

- [11] Robertson, 179.

- [12] Robertson, 25.

- [13] Henry Kyd Douglas, I Rode With Stonewall (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1940), 16-17.

- [14] Theodore G. Shuey, Jr., Ever Forward: The Story of One of the Nation’s Oldest and Most Historic Military Units (Staunton, Virginia: Lot’s Wife Publishing, 2008), xi.

If you can read only one book:

Robertson, Jr., James I. The Stonewall Brigade. Baton Rouge LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1963.

Books:

Bean, W.G. Stonewall’s Man – Sandie Pendleton. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1959.

Bean, W.G. The Liberty Hall Volunteers. Charlottesville, Virginia: The University Press of Virginia, 1964.

Casler, John O. Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade. Guthrie, Oklahoma: State Capital Print Co., 1893.

Cooke, John Esten Stonewall Jackson and the Old Stonewall Brigade. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 1954.

Douglas, Henry Kyd I Rode With Stonewall. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1940.

Shuey, Jr., Theodore G. Ever Forward - The Story of One of the Nation’s Oldest and Most Historic Military Units. Staunton, Virginia: Lot’s Wife Publishing, 2008.

Turner, Charles W. Ted Barclay, Liberty Hall Volunteers: Letters from the Stonewall Brigade 1861-1864. Natural Bridge Station, Virginia: Rockbridge Publishing Co., 1992.

Wert, Jeffry D. A Brotherhood of Valor: The Common Soldiers of the Stonewall Brigade, C.S.A. and the Iron Brigade, U.S.A. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999.

White, William S. Sketches of the Life of Captain Hugh A. White of the Stonewall Brigade by His Father. Harrisonburg, Virginia: Sprinkle Publications, 1997 (Reprint, originally published in 1862).

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

The Stonewall Brigade is a living history association dedicated to accurately portraying soldiers and civilians of the American Civil War for over 25 years.

Website devoted to the history of the 116th Regiment (formed in 1916 from the regiments of the Stonewall Brigade) which was reactivated as 1st Brigade of the 29th Infantry Division in 1985.

Other Sources:

116th Infantry Regiment Collection

A collection of artifacts and uniforms tracing the history of the 116th Infantry Regiment, America's Stonewall Brigade, will soon be on display at 566 Lee Highway in Verona, Virginia. Previously housed in the Staunton National Guard Armory, the exhibits start with displays reflecting the origins of the Regiment in 1741 and proceeding through the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, WWI, WWII, and the current War on Terrorism. In the Post 9-11 era, the security at the Armory made it practically impossible for the collection to be viewed, resulting in the 116th Infantry Regiment Foundation, Inc. relocating the valuable collection to a location easily accessible from I-64 and I-81. Long term plans include an entire building dedicated to the 116th history to be located on or near the Frontier Culture Museum property in Staunton, Virginia.