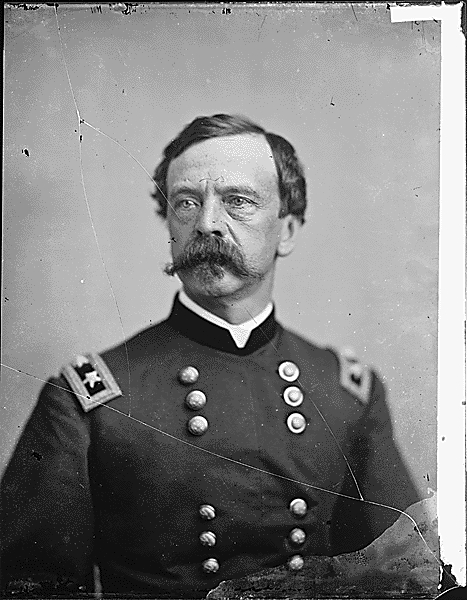

Daniel E. Sickles

by James A. Hessler

Biography of Major General Daniel E. Sickles.

Daniel Edgar Sickles was born in New York City to George Garrett and Susan Marsh Sickles. Although his birth date is generally agreed to have been October 20, there is some doubt over the year of his birth. Biographers have generally reached a consensus of 1819, but numerous contemporary sources actually have the year ranging from 1819 to 1825. If we accept the most popular 1819 as his year of birth, then Dan Sickles was a few months shy of his forty-fourth birthday when he fought at Gettysburg.

There is also little reliable information about Sickles’ early years. He simply talked infrequently of his pre-war years in later life, and as no memoirs have surfaced to date, historians are left to rely on questionable anecdotes and newspaper accounts to fill in the gaps. One accepted fact is that his father, George Sickles, was a real estate speculator whose financial fortunes fluctuated but ultimately he ended up quite wealthy. (Dan Sickles would inherit and squander a large estate from his father in later life.)

In 1838, in order to prepare him for college, Dan’s parents installed him into the household of Lorenzo L. Da Ponte, a New York University professor. The arrangement was fateful for Sickles because also residing under the same roof was Da Ponte’s adopted daughter Maria and her husband, Antonio Bagioli. The Bagiolis had one child, an infant daughter named Teresa who was born around 1836. Teresa would eventually become Dan Sickles’ first wife--- so as he was entering his twenties he was living with his wife as she was just learning to walk and talk.

Sickles opened law offices in New York in the early 1840s. He quickly gained a reputation for questionable ethics and business practices. He was indicted for obtaining money under false pretenses, was almost prosecuted for appropriating funds from another man, was accused of pocketing money that had been raised for a political pamphlet, stealing money from the post office, and charged with improperly retaining a mortgage that he had pledged as collateral on a loan.

Such accusations did not derail his entrance into politics. His political career began in 1844 when he became involved in New York’s Tammany Hall political machine. Sickles later liked to call himself “a tough Democrat; a fighting one; a Tammany Hall Democrat.” Modern politics have nothing on the practices of Sickles’ era. He was linked to stories about ballot tampering and theft, bringing in illegal voters from other districts, and brawls. He was once thrown down a flight of stairs at a campaign rally. But his star rose within Tammany Hall through the 1850s.[1]

Still a bachelor, he gained a reputation for fast and extravagant living. He was called a “lady killer” and one contemporary admitted that Sickles “led the life of a very fast young man”. Money reportedly “poured through his fingers”. He became romantically involved with a prostitute named Fanny White, who ran a high-end bordello in the city. While a member of the State Assembly, he was censured by his outraged colleagues for bringing her into the Assembly chamber. There were even rumors that he exchanged her services for campaign favors. If true, Dan Sickles may be Gettysburg’s only corps commander with “pimp” on his diverse resume.[2]

In September 1852, the nearly thirty-three year old Sickles shockingly married the Bagiolis’ daughter Teresa, then a sixteen year old student at a Catholic boarding school. Why had a rising political star married a teenager? Reports surfaced that Teresa was pregnant. Teresa gave birth to a daughter, Laura, whose birth date is unclear. There is some contemporary suggestion that it occurred in early 1853, which would potentially leave the summer of 1852 (before the marriage) open as a conception date. Married life did not, however, cure his chronic womanizing which continued for the remainder of his days.

Sickles’ career continued its upward trajectory in May 1853 when Dan accepted a post as assistant to James Buchanan, the new American minister in London. Sickles initially won over Buchanan, who was much impressed by Sickles’ abilities, and Sickles and Buchanan set sail for London in August 1853. Teresa did not initially accompany him although the prostitute Fanny White apparently did go instead. There is a story, possibly apocryphal, that he introduced the prostitute to Queen Victoria. While in London, Dan also caused an uproar by refusing to participate in a toast to the Queen’s health on July 4, 1854, a story that Sickles enjoyed telling for the rest of his life. Teresa Sickles and new daughter Laura reached London in the spring of 1854, and Teresa quickly became a favorite of Buchanan, a sixty-two year old bachelor.

Sickles would prove on several occasions during his life to be poorly suited for diplomatic service. Dan and Teresa returned to New York at the end of 1854. Decades before he would help develop Gettysburg National Military Park, he was involved in the creation of New York’s Central Park. Despite opposition, Sickles helped consolidate advocates of the park, obtained consensus on a site, and convinced the governor to sign legislation. Dan’s motives were not entirely pure; he freely admitted that he participated in a syndicate to purchase one thousand building lots near the park. Nothing came of the investment, but he continued to support the park. Nearly fifty years later, Sickles would watch thousands enjoy the park and admit, “I sometimes feel a complacent pride in the recollection that I helped to create this park.”[3]

In 1856, Sickles finally hit the national stage when he was elected to Congress, while his mentor Buchanan was also voted into the White House. Dan and Teresa arrived in Washington for Buchanan’s inauguration in March 1857 and set up their household on the fashionable and prestigious Lafayette Square, directly across the street from the Executive Mansion. President Buchanan was a frequent guest in their home. Washington wives played an important role in their husband’s careers and Teresa had significant social obligations. She was expected to attend a party almost daily. It was not uncommon for available bachelors to act as escorts for married women when their politician husbands were unavailable. Dan was meanwhile focused on his rising career. He worked late hours, traveled frequently, and probably incurred some resentment from Teresa as he continued his own philandering.

Shortly after arriving in Washington, Sickles met Philip Barton Key, a United States Attorney General and son of Francis Scott Key, composer of The Star Spangled Banner. Key’s wife had died in the 1850s leaving him with four children. He claimed that his wife’s death had shattered his health and he was increasingly inattentive to his professional duties. But his supposed poor health did not prevent his regular attendance at Washington parties where he was a favorite of every hostess and a known ladies’ man. Key was nervous that Buchanan might replace him, and Sickles generously agreed to intercede on his behalf. Thanks to Sickles, Key was reappointed to his position.

Key and Sickles soon became friends and Key increasingly accompanied Teresa to functions when Sickles was traveling or otherwise unavailable. This was not unusual by itself but gossip began to grow concerning Key and Teresa. When a young clerk was caught spreading rumors that Teresa and Key had spent time together at an inn, Sickles confronted Key, who vehemently denied the charge. Key had lied; he and Teresa were having an affair.

Key and Teresa began to meet in a rented house only two blocks from Lafayette Square. Key also took to signaling Teresa from Lafayette Square by waving a white handkerchief while standing across from the Sickles’ house. He reportedly carried a pair of opera glasses, which he would use to detect her signals from inside the house.

Unfortunately for Key, on February 25, 1859, Sickles received an anonymous letter that informed him about the house on Fifteenth Street, which Key rented as the letter said: “for no other purpose than to meet your wife Mrs. Sickles. He hangs a string out of the window as a signal to her that he is in and leaves the door unfastened and she walks in and sir I do assure you with these few hints I leave the rest for you to imagine.” After a brief investigation that confirmed the innuendo, Dan extracted a full written confession from Teresa. She admitted, in writing, to meeting with Key in the house on Fifteenth Street, as well as in the Sickles house when Dan was away.[4]

Sunday February 27 was a spring-like day. Dan Sickles spent the early morning hours sobbing hysterically and summoning political friends to the home for their counsel. The hapless Philip Barton Key was unaware of Teresa’s confession and had approached the Sickles house several times already that day. As Key passed the house, he would twirl his white handkerchief slowly, an obvious signal for Teresa to come out and play. Sickles finally noticed and shouted, “That villain has just passed my house! My God, this is horrible!” Sickles armed himself with a revolver and two derringers.[5]

Key was on the square’s southeast corner near Pennsylvania Avenue, across from the President’s Mansion. Sickles rapidly approached Key, shouting, “Key, you scoundrel, you have dishonored my house- you must die!” Sickles produced a gun and fired at close range. The first shot only grazed Key and the two men began to struggle. Key reached into his pocket and flung his opera glasses at Sickles. Sickles hit Key below the groin with a second bullet. Key fell onto the ground as Sickles pulled the trigger again. It misfired. He cocked the gun yet again, placed it on Key’s chest, and fired. This time the bullet entered below Key’s heart. Key slumped backwards as Sickles put the gun to Key’s head. Again it misfired.[6]

Since the altercation occurred in broad daylight in front of numerous witnesses, bystanders now moved in between the two former friends. Sickles stood unapologetically with the gun and asked, “Is the scoundrel dead?” Sickles was led away and Key died shortly thereafter. Congressman Sickles surrendered himself after briefly informing his wife of what he had done and was led off to jail.[7]

It is not an exaggeration to say that the murder of Philip Barton Key, and accompanying trial of Congressman Sickles, was the equivalent of the era’s OJ Simpson trial. It had everything: adultery, politics, celebrity, and murder. Newspapers across the country provided extensive coverage of the so-called “Sickles Tragedy”; it was daily front-page news and was censored for obscenity in some markets.

There was significant show of public sympathy for Congressman Sickles. Political influence aside (President Buchanan reportedly convinced one witness not to testify) many simply considered Sickles to have been a righteously aggrieved husband. There was considerable difficulty in finding an impartial jury and several candidates expressed the outright opinion that they would acquit if selected. His many friends were in evidence when the trial opened on April 4. Congressman Sickles had assembled a high-powered defense team and pleaded “Not Guilty.” The defense team has been remembered by Civil War scholars for including future Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. He was not, however, the lead attorney on the case.

Sickles’ defense team worked hard, and publicly, to portray Teresa as a “fallen woman” and Key as a criminal adulterer. Sickles’ own sexual history was not admissible and many modern observers have commented on the apparent hypocrisy of this. Sickles’ own extramarital affairs were simply not facts of the case and not considered to be the cause of the crime.

The defense team did posit that the heinous discovery of his wife with his friend had caused Sickles’ mind to become “affected” and that there had not been “sufficient time” for “his passion to cool”. It was this final point that made the trial historically noteworthy beyond its merely scandalous aspects. It is believed that the Sickles team had placed what would eventually evolve into the “temporary insanity” defense before an American jury for the first time.[8]

The jury ultimately reached a verdict of “Not Guilty.” Pandemonium and cheers broke out in the courtroom. So many people swarmed Sickles to offer their congratulations that police had to escort him out of the court. Most nationwide newspapers praised the verdict. An interview with jurymen suggested that it was not the “temporary insanity” defense that had won the Congressman’s freedom but rather the belief that Sickles was entitled to protect his wife, as a form of property, from an adulterer.

Congressman Sickles was free and generally enjoyed the goodwill of society once again, but Teresa’s reputation had been destroyed. The once youthful wife of a prominent politician would essentially fade from public life. The episode took a bizarre turn within three months, however, when Dan and Teresa reconciled. Newspapers that had supported him now turned, questioning why Teresa could be forgiven but not Key. Political friends, some of them angry with the great lengths they had gone to help him, wisely ran for cover.

The newly outcast Dan Sickles remained uncharacteristically on the sidelines when he reported back to Congress in December 1859. He had little influence, actively participated in few debates, and was ostracized by colleagues. Southern diarist Mary Chesnut famously observed Sickles “sitting alone on the benches of the Congress…He was as left to himself as if he had smallpox.” When Chesnut asked why he was such an outcast, a friend sniffed that killing Key “was all right…It was because he condoned his wife’s [adultery], and took her back…Unsavory subject.” Thus, it surprised no one when Sickles declined to run for another term. It was a shockingly swift fall from grace for both the husband and wife who had arrived in Washington with so much promise only a few short years before.[9]

Sickles would never quite live down the Key murder. Ultimately, the Key scandal’s most lasting impact on Gettysburg was the fact that it drove Sickles out of Congress. When the war started in 1861, Sickles would be looking for a new career and soon proved himself able at successfully reinventing himself. The disgraced ex-Congressman would transform himself into General Daniel Sickles.

Sickles was in New York, practicing law as a private citizen, when the American Civil War officially began in April 1861. Although Sickles had once threatened to help New York secede from the Union, he was outraged by the perceived betrayal of Southern Democrats. Sickles and a friend decided to raise a regiment which Sickles was to command. Sickles, a politician and attorney who knew how to give a good speech, proved adept at recruiting. Although some ridiculed the notion that the disgraced Sickles would lead men in combat, they eventually had enough men to form a brigade, which was potentially lucrative for Sickles since colonels commanded regiments while brigadier generals commanded brigades. They recruited about 3,000 men and Sickles dubbed his new brigade the “Excelsior Brigade” after the New York State motto (“Ever Upward”).

President Abraham Lincoln needed diverse political support, even from someone as sullied as Sickles, for his unpopular new war. Lincoln appointed numerous “political generals” as a result; men whose services were likely to win constituents but often lacked any practical military experience. Military professionals were often resentful of this practice. Lincoln assured Sickles that he needed every “Democrat of prominence…right up in the front line of the fighting.” Lincoln also liked Sickles’ aggressive nature and the two men would mutually exploit each other for the remainder of the war.[10]

Despite some initial resistance at the state level, the Excelsior Brigade finally received orders to depart for Washington in July 1861 after the Federal disaster at First Bull Run. Sickles probably now presumed that his brigadier generalship was assured. But the Senate, skeptical of his experience, motives, and reputation, delayed his confirmation for several months. Ever the opportunist, Sickles would use his time in Washington to good advantage; further ingratiating himself with Lincoln and making sure that the promotion would go through. Dan Sickles, back in the limelight and probably looking trim in his new uniform, became a frequent social visitor at the Lincoln White House and was a particular favorite of Mary Todd Lincoln. Many watched in disgust as he was said to call on her at all hours, and escort her when President Lincoln was unavailable, just as Key had done to Teresa.

Sickles began to get battlefield experience in the spring of 1862 when his Excelsior Brigade was assigned to Major General Joseph Hooker’s division in the III Corps. General Sickles saw his first major combat at Fair Oaks (or Seven Pines) on June 1. Sickles deployed the Excelsiors under fire and actually acquitted himself well; the brigade was praised in both Major Generals George McClellan and Hooker’s reports. The Excelsiors saw more action during the Seven Days’ Battles, and it was during this campaign that Sickles received the majority of his pre-Gettysburg combat experience. He then departed the brigade and spent the late summer of 1862 giving recruiting speeches and missed the Second Manassas and Antietam campaigns.

When Major General Ambrose Burnside took command of the army following Antietam, Hooker’s growing reputation carried him into command of Burnside’s new Center Grand Division, which included the III Corps under Major General George Stoneman Sickles was then promoted to command Hooker’s old Second Division of the III Corps and eventually received a major general’s commission. The promotion was an astonishing advance given that only a few months ago his brigadier generalship was in serious doubt and he had done little fighting in the interim.

At the battle of Fredericksburg, Stoneman’s III Corps consisted of 3 divisions: Major General David Birney’s First Division, Sickles’ Second Division, and Brigadier General Weeks Whipple’s Third Division. On December 13, 1862, Sickles and Birney’s divisions were ordered to support Major General John Reynolds’s attacks from the Federal left against Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s lines south of Fredericksburg. One of Reynolds’s divisions under Major General George Meade actually broke a hole in Jackson’s lines, but Meade had no support on his flanks and was ultimately driven back in confusion.

Although Reynolds praised General Birney’s performance, Meade blamed Birney for not directly supporting his attack. Birney resented Meade’s criticism, and when Meade later took command of the Army of the Potomac, it was said that Meade was hated in the III Corps particularly by Birney. As Sickles and Birney became friends, it is reasonable to speculate that Sickles received his first negative impressions of Meade from Birney.

Sickles meanwhile saw almost no combat at Fredericksburg. As 1863 dawned, Sickles was commanding a division in the Army of the Potomac but had still not really seen any major action since leading a brigade during the summer of 1862. Sickles might have had the makings of a good combat officer. He had the aggression, the intellect (as a lengthy career in law and politics would suggest), and the patriotic fervor to be successful. But he simply lacked practical experience maneuvering large bodies of men in combat and was also missing the theoretical (if sometimes impractical) West Point education of a professional soldier.

Fredericksburg’s bloody failure led inauspiciously into 1863. When General Burnside was relieved in January, Abraham Lincoln promoted Joseph Hooker to command the Army of the Potomac. One of Hooker’s first orders of business was to settle on his staff. Hooker appointed New Yorker Major General Daniel Butterfield as his chief of staff. Like Sickles, Butterfield was not West Point. Generals Butterfield and Meade also had a past unfriendly history together. Many officers would learn to hate Butterfield in his new role as the army’s chief of staff.

As Hooker reorganized his new army, and although Sickles had commanded a division during only one battle in which he saw little combat, Hooker placed him in command of the III Corps. As the highest ranking non-West Pointer in the army, a distinction he would carry into Gettysburg, Sickles’ rise to major general and command of the III Corps was an amazing accomplishment, even for that politically charged army.

Sickles, Hooker, and Butterfield now became friends. Life in winter quarters was dull and tedious. After Hooker’s promotions, much of the Army of the Potomac’s efforts in early 1863 seemed to focus on throwing parties to relieve the monotony. Hooker had a reputation as a womanizer and hard drinker, mostly from his pre-war days in California. Sickles had murder on his resume and his own adulterous tendencies continued while Teresa was shunned at home in New York. Dan Butterfield had perhaps the most bizarre background of the three men: as a youth he had been arrested for arson. During the winter of 1863, these three men set the army’s social and morality standards. Captain Charles Adams famously complained: “The Army of the Potomac sank to its lowest point. It was commanded by a trio, of each of whom the least said the better… During that winter (1862-3) when Hooker was in command, I can say from personal knowledge and experience that the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac was a place to which no self-respecting man liked to go, and no decent woman would go. It was a combination of bar-room and brothel.”[11]

One general who was decidedly excluded from this social calendar was the new V Corps commander, George Meade. Already unpopular in the III Corps and resented by the new chief of staff, Meade had no interest in their social vices and held the regular soldier’s healthy dose of disrespect for amateurs like Sickles and Butterfield. Throughout that winter, Meade was regularly excluded from Hooker and Sickles’ parties, much to Meade’s chagrin.

The Battle of Chancellorsville was fought only two months before Gettysburg, in May 1863, and General Hooker was soundly beaten in his only battle commanding the Army of the Potomac. Chancellorsville was significant in that Sickles saw major combat for the first time at his level. Sickles’ III Corps suffered 4,100 of the 17,000 Federal casualties at Chancellorsville. Sickles also displayed an ability to misinterpret battlefield intelligence when he discovered Stonewall Jackson’s legendary flank march in progress and misinterpreted it as a retreat. Sickles then displayed aggressive but questionable judgment when he ordered a midnight attack in the Wilderness on the night of May 2. Finally, on May 3, Sickles along with more than 30 artillery pieces was withdrawn by Hooker from a key artillery position called Hazel Grove which the Confederate batteries then used to pound Hooker out of his position. Military historians have argued that Hazel Grove influenced Sickles’ actions at Gettysburg, although no account has yet surfaced in which Sickles attributed it as a direct influence.

After the crushing Federal defeat at Chancellorsville, Hooker decided to retreat across the Rappahannock River. When criticism of Hooker started appearing in the press afterwards, Meade was outraged by reports that he also favored a retreat. When Meade asked Sickles for his recollections and support, Sickles instead sustained the line that Meade had agreed with Hooker’s retreat. Meade undoubtedly remembered this when he assumed command of the army only weeks later.

General Hooker resigned his command on June 28 following a series of disagreements with Washington over his orders. Lincoln selected George Meade as Hooker’s successor. Sickles was clearly out of favor with army headquarters, for the first time, and still had little experience acting independently at the corps level. Meade quickly became critical of Sickles’ movements as the army began to march north in pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia which had entered Pennsylvania. Working against Meade was the fact that Meade was forced to keep Dan Butterfield as Chief of Staff, after several other officers declined Meade’s offer to assume the role, a move Meade would surely come to regret.

On the morning of July 1, Meade issued contingency orders for the army to fall back onto a defensive line at Pipe Creek in Maryland. Sickles and his III Corps were positioned at Emmitsburg in case Lee should attempt to flank the Federal left. General John Reynolds had moved his I Corps to Gettysburg that morning and as fighting escalated there both Generals Reynolds and Major General Oliver Otis Howard of the XI Corps requested Sickles to come to Gettysburg. Sickles became paralyzed with indecision and did not reach Gettysburg until 7:00 p.m. on July 1, after the fighting was over. Historians have generally credited Sickles with “marching to the sound of the guns” but his delay of several hours did prevent critical reinforcements from reaching the field and might have blunted the Federal defeat on Gettysburg’s first day.

Dan Sickles will ultimately be best remembered for his actions on July 2 at Gettysburg. That morning, Meade ordered Sickles to anchor the left end of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge which included Little Round Top. Meade and the Union high command were centering their line on Cemetery Hill (the hook in the famous Union “fish hook”), but were concerned that their flanks might be vulnerable. Portions of a division in Major General Henry Slocum’s XII Corps protected the Federal left during the evening of July 1, but Meade wanted the XII Corps reunited on the Union right at Culp’s Hill, so he ordered Sickles to replace them on the left. In doing so, it was expected that Sickles would also extend the left of Major General Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps (on Sickles’ right) and occupy a range of hills (the Round Tops on Sickles’ left) that were considered plainly visible. These orders appear to have been verbal and the time in which they were originally delivered is a matter of debate. Around 9:00 a.m. on July 2, Meade sent his son and aide, Captain George Meade, to locate Sickles and ensure that the III Corps was in position. But Sickles would not come out of his tent to speak with Captain Meade and instead had his artillery captain relay a message that Sickles was confused over his orders.

Captain Meade rode the short distance back to his father’s headquarters. General Meade impatiently repeated his instructions, which sent Captain Meade back to the III Corps commander once again. This time Sickles and staff were mounted and heading off to the front. Sickles again indicated that he was uncertain over where he should be. Trouble was brewing on the Federal left.

Sickles’ numerous historical critics have accused him of blatantly, willfully, and defiantly disobeying clear orders from General Meade due to their mutual dislike of each other. In the most extreme scenario, Sickles has even been accused of acting with Presidential aspirations of his own, that a bloody battle would somehow elevate him to the White House. This theory is totally without historical support. General Meade himself later acknowledged that the verbal orders included those words that are at the heart of so many Civil War controversies: “if it was practicable to occupy it [Little Round Top].”[12]

Sickles claimed that the confusion arose from the fact that the XII Corps division “was not in position, but was merely massed in my vicinity.” Sickles and other III Corps officers also acknowledged, however, that as the sun rose that morning they became increasingly concerned about the low ground north of Little Round Top and the fact that it could be dominated by enemy artillery along the higher ground of the Emmitsburg Road to the west. Sickles later professed anxiety about getting out of the “hole” and onto seemingly higher ground from which he could better see the enemy’s approach and give his artillery more room to maneuver.

Those who criticize Sickles for openly defying Meade’s wishes also ignore the fact that at about 11:00 a.m. Sickles ventured to Meade’s headquarters and requested the commander’s assistance in posting his troops. Meade declined to leave headquarters, and also denied the use of chief engineer Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, before allowing artillery Chief Henry Hunt to accompany Sickles. (Meade also told Sickles at this meeting that Sickles could exercise some judgment in posting his troops “but only within the limits of the general instructions” that Sickles had been given. Despite this conversation, Meade later claimed that he was unaware that Sickles harbored any doubts about his position.) Before departing headquarters, Sickles also apparently learned that Butterfield was working on an apparent retreat order from Gettysburg. In reality, Meade had asked for this to be prepared as a contingency, but Sickles and Butterfield misrepresented (perhaps willfully) the nature of this order afterwards to portray Meade as not wanting to fight at Gettysburg.[13]

As they rode along Cemetery Ridge, Sickles surprised General Hunt by informing Hunt that he wanted to move his III Corps forward to a line that was centered along the Emmitsburg Road and was roughly half a mile in front of Cemetery Ridge. General Hunt did not authorize Sickles to advance, but did advise Sickles to reconnoiter Pitzer’s Woods on the west side of the Emmitsburg Road. This reconnaissance seemingly discovered Confederate troops in motion and led to a brief but spirited firefight. At the same time, Major General John Buford’s Union cavalry that was screening Sickles’ front was mistakenly withdrawn. Sickles now became convinced that the enemy was moving on his flank and with no cavalry to screen him, he decided that it was time to act. Sickles was, despite any other personality defects, a man of action. By early afternoon, he moved his roughly 10,000 man III Corps forward from Cemetery Ridge. General George Meade remained unaware of this fact for several hours.

Sickles’ new line ran from landmarks known today as Devil’s Den (on the left) through the Wheatfield, to the Peach Orchard (in the center) and then ended along the Emmitsburg Road. Sickles’ new position held several disadvantages for the III Corps. They were too far in advance of Meade’s army to readily receive support. Meade’s reinforcements had to cover the additional half mile of open ground to reach Sickles; negating the interior lines of Meade’s “fish hook.” The essentially straight line along Cemetery Ridge, which Meade intended Sickles to occupy, was approximately 1,600 yards in length. Sickles would later claim that he lacked sufficient strength to man Meade’s front. Yet the new position covered a front that was nearly twice as long; approximately 3,500 yards. Despite his efforts to refuse them, his flanks were in the air.

One of the biggest criticisms directed at Sickles was that by moving forward he abandoned Little Round Top—viewed by many as the key to the Union left because it was the highest defensible point in the immediate vicinity. Although Sickles may not have properly understood its value on July 2, 1863, he obviously did come to realize it during the next fifty years of his life as he would often falsely claim that he did occupy Little Round Top and supervised the placement of reinforcements up there.

Meade did not learn of Sickles’ actions until nearly 3:00 p.m. Upon word from General Warren that Sickles was not where Meade intended, Meade finally journeyed to the Peach Orchard to examine the situation personally. General Meade expressed his displeasure and Sickles was in the act of offering to pull back when Confederate artillery opened fire on the position. Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet had spent several hours getting into position opposite the Union left and his forces were now ready to attempt to outflank Meade’s army. With enemy shells flying overhead, Meade decided to keep Sickles in position and instead would spend the afternoon throwing reinforcements onto his left flank. It was a questionable decision in hindsight, throwing in troops to support a known defective position, but Meade’s options were limited and he had to act quickly since Longstreet’s attack was underway. Sickles, for his part, would use this decision to his advantage in his post-battle feud with Meade. Sickles would argue repeatedly over the years that Meade approved his new position because he did not pull him out of it!

Longstreet’s attack began at 4:00 p.m. and after the bloodiest fighting at Gettysburg, Sickles’ III Corps was driven out of Devil’s Den, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard, and the Emmitsburg Road with heavy losses. This outcome, despite the fact that Meade supported Sickles with portions of Hancock’s II Corps, General Major George Sykes’s V Corps, Major John Sedgwick’s VI Corps, and the Artillery Reserve seemingly proves that Sickles had moved into an indefensible position. Sickles’ III Corps was effectively finished as an organized body as were several of the brigades that were hurried to his assistance.

At the same time, Sickles’ position helped further stretch Longstreet’s already overextended line. Longstreet’s corps was severely bloodied capturing positions that later proved meaningless (such as the Peach Orchard) and Longstreet failed to drive in the Union left as intended. Whether or not Sickles conducted a legitimate (or even accidental) “defense in depth” is just one of the many points that Gettysburg enthusiasts argue, but the fact remains that Sickles caused Longstreet to fight for positions that ultimately did not help General Robert E. Lee win the Battle of Gettysburg. What the outcome might have been had Sickles remained in Meade’s intended position will never be known and cannot be argued with any certainty. Most historians today firmly believe that Sickles severely hurt the Union cause at Gettysburg, but the day’s actions badly damaged both armies and Meade still held Cemetery Ridge when it was over.

Late in the afternoon, perhaps 6:30 p.m., Sickles was attempting to rally his crumbling line, when a Confederate artillery shell smashed into his right leg. Sickles was carried from the field and his leg was amputated that evening. His career was seemingly over once again, yet the loss of his leg was arguably one of his greatest career moves. He would survive for another fifty years portraying himself as the one-legged hero of Gettysburg, attending battlefield reunions and veteran gatherings with a crutch and missing leg as a permanent reminder of his sacrifice. Mark Twain met Sickles in later years and drew the astute observation that Sickles “valued the leg he lost more than the one he’s got” and “I’m sure if he had to part with one he would prefer to lose the one he still has.” Sickles also donated the leg bone to the fledgling Army Medical Museum in Washington and reportedly visited it regularly.[14]

The Battle of Gettysburg—viewed as a great victory today—was considered a disappointment in the North because Meade was unable to prevent Lee from escaping back into Virginia. While recuperating from his wound in Washington, Sickles was frequently visited by his friend Abraham Lincoln. During these visits Lincoln expressed his disappointment that Lee’s army had seemingly escaped. It seems clear that Sickles helped reinforce Lincoln’s displeasure. Sickles recuperated surprisingly quickly and by October 1863 returned to Meade in the field and asked for his command back. Meade declined the request on the grounds that he was no longer physically fit for active service.

It was this disappointment that led into the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War’s Gettysburg hearings in the spring of 1864. The committee called nearly all of Meade’s senior officers to testify. Their first witness was Dan Sickles. Sickles was angry that Meade refused to allow his return to the army and was smarting under mild criticism that he had received in the reports of Meade and General-in-Chief Henry Wager Halleck. Criticism of his failure to occupy Little Round Top was also entering the public domain. Sickles insisted, for better or worse, that he had not misinterpreted Meade’s orders and that he thought he was taking commanding ground. Sickles used Congress as an opportunity to justify his decision to move forward—even going so far as to lie and tell Congress that he did in fact occupy Little Round Top. He also began his fifty year assault on George Meade by claiming that Meade had wanted to retreat on July 2, and that his advance had prevented Meade from abandoning Gettysburg. This is the heart of the so-called “Meade-Sickles controversy.” Sickles never said it in so many words, although his friends sometimes did on his behalf, but the implication was clear: Dan Sickles deserved credit for keeping the army at Gettysburg and thus was responsible for much of the victory.

Although these arguments caused Meade a large measure of discomfort, he ultimately retained command of the Army of the Potomac for the remainder of the war and most historians today support Meade’s version of the events. He reportedly told a friend before his death in 1872 that, “Sickles’ movement practically destroyed his own corps… [and produced] 66 per cent of the loss of the whole battle, and with what result- driving us back to the position he was ordered to hold originally.” Meade claimed these crippling losses prevented him “from having the audacity in the offense that I might otherwise have had”, laying the blame for Meade’s inability to destroy Lee’s army right back into Sickles’ lap. “If this is an advantage- to be so crippled in battle without attaining an object—I must confess I cannot see it”.[15]

After the war, Sickles was most concerned (like many veterans) with resuming his life. He spent the late 1860s – 1870s on Reconstruction Duty and then served as Minister to Spain. Teresa Sickles died unexpectedly in 1867, leaving him a bachelor again. In Spain, he regained his reputation for entertaining lavishly, well above his annual salary. Dan began a romantic affair with the deposed Queen Isabella II in Paris and the French press sarcastically dubbed him the “Yankee King of Spain”. But in November 1871, he instead married one of Isabella’s twenty-something attendants, Caroline de Creagh. Sickles resigned his position in 1873 after a dispute with the secretary of state and moved to Paris for several years. While in Europe, Caroline bore a daughter (Eda) in 1875 and a son (George Stanton) in 1876. Approaching fifty-seven years old, and with a significant physical disability, Sickles was starting a new family at an age when most men were preparing to retire. In late 1879 he decided to return to the United States. His return coincided with the desire of the old Civil War veterans’ to commemorate the war and Gettysburg in large numbers. Given his organizational abilities, and without anything substantial to regularly occupy his time, he threw himself full-blown into veterans’ affairs.

As a popular guest speaker at reunions, Sickles was frequently asked if he regretted his Gettysburg actions. Sickles would repeatedly declare, “I would do tomorrow under the conditions and circumstances that then existed exactly what I did on July 2.” In reflecting upon almost thirty-six years of controversy in 1899, “I have heard all the criticisms and read all the histories and after hearing and reading all I would say to them I would do what I did and accept the verdict of history on my acts. It was a mighty good fight both made and I am satisfied with my part in it.” He was characteristically unrepentant to the bitter end.[16]

Sickles is despised by many Gettysburg aficionados today for seemingly blundering on the battlefield, causing thousands of Union casualties, and then more so for his very public attacks on General Meade during the decades that followed. But lost on many is the fact that Sickles cared deeply about preserving the Gettysburg battlefield for the veterans and for future generations. He was, in fact, one of Gettysburg’s most influential early preservationists.

The year 1886 officially changed the nature of Sickles’ involvement with the Gettysburg battlefield. He was appointed the chairman of the New York Monuments Commission for the Battlefield of Gettysburg. For nearly the remainder of his life, Sickles would be consumed by a mission to appropriate and correctly place monuments to all New York regiments, batteries, and ranking commanders on the battlefield. These new monuments would require dedication speeches, typically in front of enthusiastic veterans. Sickles’ new role ensured that he would become a welcome staple at battlefield reunions; refighting the battle to an assorted cast of aging veterans and an increasing number of attendees who had not yet been born when he made his controversial move to the Peach Orchard.

During this period, Dan also befriended James Longstreet, his Gettysburg opponent. The two men increasingly became friends during their twilight years, sharing the distinction of having their Gettysburg performance assailed by critics on both sides. Whether they actually believed it or not, each man would frequently tell anyone who would listen that the other had done right on July 2, 1863. It was a unique measure of Sickles’ personality that although he would never make peace with former comrades like General Meade, and often feuded with members of his own family (his daughter Laura died estranged from her father as a penniless alcoholic), the former Confederate whose men had shot off his leg became one of his most valued friends.

A surprising development occurred in 1892 when Sickles was re-elected to Congress— over thirty years after he had been disgraced by the Key murder. The New York Times would later marvel that Sickles was returning at “an age when most men are ready to retire.” The most lasting act of his long public career was his 1894 introduction of legislation that was signed into law on February 11, 1895, and created Gettysburg National Military Park. The man who helped create Central Park, gave posterity the “temporary insanity” defense, and may have nearly lost the Battle of Gettysburg helped create one of the nation’s most revered National Parks, an accomplishment that is virtually unknown to millions of Americans.[17]

By the early 1890s, Sickles was not only still active but also very wealthy. He had inherited an estate valued between $4 and $7 million from his father, but as he demonstrated throughout his life, placing large sums of money in his hands was always a precarious proposition. Within years he was bankrupt.

Sometime during his later years in New York, Sickles became attached to a housekeeper by the name of Eleanor Wilmerding. Sickles’ second wife Caroline and now adult-son Stanton sailed from Europe to New York in 1908. Despite the fact that he had now been away from them for nearly three decades, both seemed to genuinely hope for reconciliation. Caroline even paid some of Sickles’ debts but demanded in return that Sickles dismiss Wilmerding from his house. Sickles refused to fire Wilmerding so an exasperated Mrs. Sickles and son Stanton were instead banished to a nearby hotel. The whole soap opera was replayed enthusiastically in the New York newspapers and once again Sickles’ marital life was in the news for all the wrong reasons.

It was against this backdrop that the battle’s fiftieth anniversary, and the end of Dan Sickles’ Gettysburg adventure, arrived in 1913. The general was now in his early nineties, failing mentally, nearly blind, and confined to a wheelchair. It was readily apparent that he was no longer capable of managing his own household affairs, let alone the finances of an organization like the New York State Monuments Commission. Several months prior to the Gettysburg anniversary, New York State’s controller performed an audit of the commission’s books and found that over $28,000 was unaccounted for. New York was serious about recouping its money and even considered throwing him in jail. A last minute deal helped Sickles avoid incarceration, but he was embarrassingly deposed from the New York Monuments Commission. It is also believed that these financial troubles prevented a Sickles monument from being placed on the Gettysburg battlefield.

If the early months of 1913 represented one of the lowest points of Sickles’ public life, then the summer still held the promise of Gettysburg’s fiftieth anniversary celebrations. When July 1913 finally and mercifully arrived, newspapers across the country covered the massive Blue and Gray reunion of at least 50,000 veterans. Only a few months shy of his ninety-fourth birthday, Sickles arrived in a wheelchair accompanied by Wilmerding and his valet. This time, his age and infirmity prevented him from making any extended speeches. He was undeniably a center of attention and newspaper reports consistently updated readers on his movements.

Legend tells us that as Sickles and his friend, Chaplain Joe Twichell, looked out over the field together for one last time, Twichell is said to have expressed surprise that there was still no Sickles statue on the field. Sickles allegedly replied (to the effect) that the whole damned battlefield was his monument. While we may never see a Sickles statue on the battlefield, his presence is, in fact, nearly everywhere:

The lengthy “Sickles Avenue” runs over much of his line of battle.

The Excelsior Brigade monument, even without his alleged missing bust, commemorates both him and the men he raised in New York.

The marker near the Trostle farm denotes where he was wounded, while the New York Monument in the National Cemetery depicts the dramatic moment.

The back-side of the Lincoln Speech Memorial, dedicated in 1912, credits Sickles with introducing the legislation that established the park and erected the monuments.

His name sits at the top of the New York Auxiliary State Monument, dedicated in 1925 (after his death) to the memory of all New York commanders who were not individually honored elsewhere.

Under his preservation leadership, New York placed eighty-eight monuments on the battlefield, the state monument in the National Cemetery, statues to two generals (Slocum and Greene), and applications for two more (Wadsworth and Webb).

Locales such as Devil’s Den, the Wheatfield, and the Peach Orchard might not have any significance today were it not for his 2 July advance.

He established the Park’s initial boundaries.

Even the fence separating the National Cemetery and the local Evergreen Cemetery was the same that stood in Lafayette Square when Dan killed Barton Key.

The “whole damn battlefield” might not be his monument, but he certainly has his share of it.

Less than one year after making his final visit to Gettysburg, Dan Sickles suffered a cerebral hemorrhage on April 24, 1914. Lingering in semi-consciousness, he was surrounded by Caroline Sickles, his son Stanton, his attorney, and a nurse when he died at his Fifth Avenue home during the evening of May 3. Although his obituary contributed to the confusion over his age by noting that he “lived to be almost 91”, he was more likely six months short of his ninety-fifth birthday.

There was some thought that Sickles would be buried at Gettysburg, but his attorney came forward and stated that Sickles had preferred to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Remembered by Civil War historians as one of the war’s most notorious amateur soldiers and political generals, Sickles rests as a soldier in the nation’s premier military cemetery.

The New York Times eulogized “a stirring” career. He was remembered as a “soldier, politician, and diplomat…the last of that galaxy of corps commanders who made possible the achievement of Grant and brought our great civil strife to a triumphant close.” Sickles’ lengthy career is primarily remembered today for Gettysburg. One can only assume that he would enjoy the fact that nearly one century after his death, the mention of his name can still evoke heated arguments amongst the enthusiasts of America’s most studied battle.[18]

Daniel Edgar Sickles

- [1] Joseph Beatty Doyle, In Memoriam, Edwin McMasters Stanton, His Life and Work; Wit (Steubenville, OH: Herald Printing, 1911), 374.

- [2] Nat Brandt, The Congressman Who Got Away with Murder (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1991), 25, 36; W.A. Swanberg, Sickles The Incredible (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1956), 83.

- [3] Manuscript, “The Founder of Central Park, in New York”, n.d., Daniel Edgar Sickles Papers, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress.

- [4] Swanberg, Sickles, 46.

- [5] Brandt, The Congressman, 117.

- [6] Felix G. De Fontaine, Trial of the Hon. Daniel E. Sickles for Shooting Philip Barton Key, Esq., U.S. District Attorney, of Washington, D.C., February 27th, 1859 (New York: R.M. DeWitt, 1859), 4.

- [7] New York Times, April 9, 1959; Swanberg, Sickles, 54.

- [8] De Fontaine, Trial, 25-32.

- [9] Mary Boykin Chesnut, Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, ed. C. Vann Woodward (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1981), 379-80.

- [10] New York Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg, Chattanooga and Antietam, Dedication of the New York Auxiliary State Monument on the Battlefield of Gettysburg Authorized by Chapter 181 Laws of 1925 (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, printers, 1926), 107.

- [11] Gary Lash, “The Congressional Resolution of Thanks for the Federal Victory at Gettysburg,” Gettysburg Magazine 12 (January 1995): 85-96.

- [12] Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, H.R. Rep. No. 38(2) 3 parts, vol.1 at 331 (1865).

- [13] George Meade Life And Letters Of George Gordon Meade Major-General United States Army, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), 2:70-1; Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Report, vol.1 at 298.

- [14] Mark Twain, Mark Twain’s Autobiography, 2 vols. (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1924), 339-40.

- [15] Meade, Life and Letters, 2:354.

- [16] Gettysburg Compiler, June 6, 1899.

- [17] New York Times, May 4, 1914.

- [18] New York Times, May 4, 1914

If you can read only one book:

Hessler, James A. Sickles at Gettsyburg: The Controversial Civil War General Who Committed Murder, abandoned Little Round Top, and Declared Himself the Hero of Gettysburg. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2009.

Books:

Brandt, Nat. The Congressman Who Got Away with Murder. New York: Syracuse University Press, 1991.

De Fontaine, Felix G. Trial of the Hon. Daniel E. Sickles for Shooting Philip Barton Key, Esq., U.S. District Attorney, of Washington, D.C., February 27th, 1859. New York: R.M. DeWitt, 1859.

Hessler, James A.“Sickles Returns.” Gettysburg Magazine 34 (January 2006): 64-85.

———. “Blowing Smoke,” America’s Civil War, no.3 (July 2009): 46-53.

Hyde, Bill, ed. Gettysburg Day Two: A Study in Maps. Baltimore: Butternut & Blue, 1999.

Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987.

Swanberg, W.A. Sickles The Incredible. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1956.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

The Arlington National Cemetery website includes articles and photographs relating to Daniel Sickles.

This website supports Jim Hessler’s book Sickles at Gettysburg and includes a brief biography and relevant photographs on this page.

This website gives details about Jim Hessler’s Gettysburg battlefield tour of historic sites related to General Sickles.

Other Sources:

This website gives details about Jim Hessler’s Gettysburg battlefield tour of historic sites related to General Sickles.

The Library of Congress holds the Daniel Edgar Sickles papers in the Manuscript Division. The finding aid is http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms011120 . The papers are open to research and can be accessed at the Library of Congress Manuscript Reading Room. Researchers are advised to contact them in advance. The Manuscript Reading Room is located at 101 Independence Ave. SE, Room LM 101, James Madison Memorial Building, Washington, D.C. 20540-4690, (202) 707-7791, Monday –Saturday 8:30 a.m.- 5:00 p.m