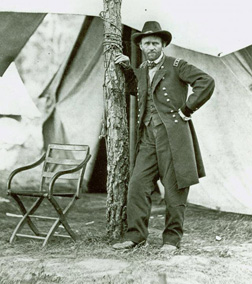

Ulysses S. Grant

by Joan Waugh

Biography of Ulysses S. Grant

Commanding general of the Union Army, and eighteenth president of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant was born on April 27, 1822 in Point Pleasant, Ohio. The oldest child of Jesse and Hannah Simpson, Grant was raised on the rough-hewn Ohio frontier first in Point Pleasant and then in nearby Georgetown. The young Hiram Ulysses (his first and middle names were later changed to Ulysses Simpson) struggled to live up to his ambitious father’s high expectations. Hiram was sensitive, often in ill health, but well educated for the time and place. He was temperamentally unfit for the family leather goods business, making Jesse’s decision to send “Lyss” to West Point a wise one, in retrospect. During his four years at the U.S. Military Academy (1839-1843) Grant was a middling student, but a superb horseman.

A few years after graduation from West Point, Lieutenant Grant fought in the Mexican War (1846-48). Although his quartermaster duties largely kept him from most battles, he won promotion and congratulations at two engagements, Monterrey and Chapultepec, showing great courage and skill as a soldier. Grant demonstrated a talent for fighting, and even more, displayed an impressive knowledge of the strategy and tactics of warfare learned from experience, not textbooks.

Despite his good record in the war, and a happy marriage to the sister of a West Point classmate, Grant did not do well in the peacetime army of the late 1840s and early 1850s. Surviving a dangerous journey from New York Harbor to the West Coast, Captain Grant increasingly missed his wife and growing family, suffered financial setbacks, enduring a lonely and boring existence in remote forts in Oregon and California. Grant took to drinking, officially resigning from the army on April 11, 1854. His actions during this period clouded an otherwise stellar military record. The civilian world proved just as difficult. Grant failed as a soldier, and then failed as a provider for his family, as a farmer, and as a businessman. He lived on his father-in-law’s land outside of St. Louis, Missouri, until moving in 1859 to Galena, Illinois to work as a clerk in his father’s store. Although these years were a low point in his life, there were some happy times. He was a loving husband to Julia Dent Grant, and an unusually attentive and affectionate father to their four children, Fred, Ulysses Jr., Jesse, and Nellie. When the guns of Fort Sumter fired, Grant was anxious to serve his country.

After briefly holding a series of low-level positions, Lieutenant Colonel Grant was given command of the Twenty-first Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Rising swiftly through the ranks, Brigadier General Grant was placed in command of the big Union supply and training camp at Cairo, Illinois. Anxious to lead in battle, he demonstrated some needed mettle for the lagging Union cause in May and November, 1861 in Missouri at Salt Lick and Belmont. After the former, Grant recalled that he learned a valuable insight into the enemy’s psyche. “I never forgot, he wrote, “that he had as much reason to fear my forces as I had his. The lesson was valuable.” In the fall and winter of 1861/62 Grant used his troops aggressively, and in conjunction with the U.S. Navy, captured the strategically important Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. When the Confederate commander of Fort Donelson sent Grant a note to discuss the terms of surrender for his army of 21,000 men, he received these words in reply: “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.”

Now famous as “Unconditional Surrender,” Grant continued to display the kind of strong generalship that brought him to the favorable attention of President Lincoln and the victory-starved North. Overcoming thorny relations with the top western commander, General Henry W. Halleck, Grant pressed his advantage after Fort Donelson, planning an attack on the Confederates at their new stronghold in Corinth, Mississippi. He concentrated his troops at Pittsburg Landing on the west bank of the Tennessee River little expecting Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnson to launch a surprise attack on the sleeping Union camps at dawn on April 6, 1862. The resulting two-day battle of Shiloh was a hard won and controversial victory. The bloody engagement (23,000 casualties) caused shock among the northern populace, and harsh criticism arose over Grant’s alleged incompetence. Still, Shiloh fell into the victory column. Grant was appointed to command the entire District of Tennessee in June 1862 with orders to secure the entire Mississippi River, executing the next phase of President Abraham Lincoln’s plan for the Western Theater.

The capture of Vicksburg, a small city perched atop bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River, ranks as one of the greatest military campaigns in history. A critical link between the eastern and western halves of the Confederacy, Vicksburg’s natural protections were enhanced considerably by manmade fortifications and the presence of a 30,000 Confederate army commanded by Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton. Grant’s earliest efforts to penetrate the “impregnable fortress” in late 1862 and early 1863 were met with failure and disappointment. In March and April he came up with the winning plan. Assisted by the naval forces under the command of David D. Porter, Grant marched his forces down the west side of the Mississippi River below Vicksburg where Porter’s boats transported two of Grant’s corps safely across the river. The next two and a half weeks saw Grant’s army moving quickly east and then west again, defeating Confederate troops at Port Gibson, Raymond, Jackson, Champion Hill, and Big Black River. Arriving at Vicksburg on May 19 Grant immediately ordered two frontal assaults that promptly failed. “I now determined upon a regular siege,” Grant declared, “to ‘out-camp the enemy,’ as it were, and to incur no more losses.”

By late June, the Federal Army had encircled the Vicksburg fortifications and its heavy cannons were shelling the beleaguered city. After forty-seven days, General Pemberton agreed to surrender his army to Grant on July 4, 1863. Vicksburg’s fall secured Union control of the Mississippi River, split the Confederacy in half and delivered a devastating blow to Southern morale. Perhaps Vicksburg’s most important outcome was embodied in Lincoln’s words upon hearing of the great western victory: “Grant is my man, and I am his, the rest of the war.”

Quickly, Grant was promoted to major general and appointed head of the Military Division of Mississippi. He now turned his attention to rescuing the trapped Federal forces in the important city of Chattanooga, Tennessee. A daunting task, Grant reopened the city’s supply lines, relieving the starving soldiers and prepared to mount attacks on the strong Confederate positions on Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge in late November 1863. Again, Grant was successful, and his victory secured Chattanooga, Knoxville, and eastern Tennessee for the United States, leaving the Confederate western military command reeling. At this time, Grant emerged as the most successful Union general of the Civil War. The victories at Fort Donelson, at Shiloh, at Vicksburg, and at Chattanooga demonstrated Grant’s strategic abilities combined with tactical success. Lincoln wanted to appoint him the commander-in-chief of the Union armies, but hesitated over his concern that the wildly popular Grant might have presidential ambitions for 1864.

He need not have worried, for Grant soon found a way to assure Lincoln of his utter disinterest in running for the highest office. Indeed, Grant and Lincoln would come to enjoy an unusually close relationship. Grant developed political skills that complimented his military abilities. Unlike some other top Union generals, Grant believed firmly that the president’s role as commander-in-chief of the war was never to be questioned – even if he disagreed with an order. For example, Grant did not like the fact that many “political” generals were appointed just because they were popular figures back home whose support Lincoln thought important to cultivate. Nevertheless, he accepted the reality and worked with the situation. Grant was an enthusiastic supporter of most of Lincoln’s policies, however, especially the use of black soldiers. Lincoln realized that he had found the general who would lead the country to victory. On March 9, 1864, the newly appointed Lieutenant General Grant accepted command of all the Union Armies in a White House ceremony.

Grant did not rise to his position without controversy. As he progressed up the chain of command, he was increasingly subject to attacks on his character and generalship. Charges of drinking, incompetence and a brutal indifference to death and suffering dogged him throughout his career, and affected his reputation after the war as well. The historical evidence unearthed on his drinking suggests that it rarely interfered with the performance of his duties. The evidence also shows that Grant did make mistakes. For example, he was caught unprepared for the Confederate attacks at Shiloh; his assault on Cold Harbor in 1864 was a disaster; and in an ill-advised and notorious order (deeply regretted) issued in 1862, he banned Jews from trading cotton, prompting charges of anti-Semitism. None of his mistakes, however, seemed to dent his growing reputation as the symbol of Union military victory. Grant had approximately two months – until May 4, when he crossed Virginia’s Rapidan River to commence the six week Overland Campaign – to master the Eastern theater and convince the roughly 120,000 troops of the Army of the Potomac that he warranted their loyalty and trust.

As Lincoln requested, Grant devised a plan for the spring and summer campaign of 1864. Grant’s plan involved the movement of all Union armies at the same time to attack and defeat the Confederates, removing their option of shifting troops around as needed. He stressed his desire to defeat the Army of Northern Virginia while directing major campaigns in Georgia, Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, and Louisiana. The plan drew Lincoln’s warm support and raised the hopes of the Northern nation for a quick end to the war. Unfortunately, winning took longer than expected.

The battles of the six week Overland Campaign, where Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee’s armies fought to bloody stalemate in the Wilderness (May 5-6), Spotsylvania (May 8-20), North Anna (May 23-26) and Cold Harbor (June 1-3) gave rise to the nickname of “butcher” for the general-in-chief whose main strategy seem to be throwing bodies at the enemy. Despite the heavy losses, most northerners were willing to give Grant’s campaign more time. On May 11 Grant sent a widely published message to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton stating, “I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.” His statement rallied a public and a president used to Union commanders who would pull back and stop fighting in the face of battle set-backs, thereby prolonging the war. Subsequent military historians have ably defended Grant against the butcher charge, pointing out that Lee lost many more men in proportion, than did Grant. Indeed, Grant met every challenge of 1864, including the difficulty in directing the Army of the Potomac against the audacious Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Cold Harbor ended weeks of nonstop campaigning for both armies. The casualties exacted a terrible toll. The North suffered 50,000 losses to the South’s 32,000. On June 12 Grant crossed the James River to seize Petersburg, an important rail center. He believed that if Petersburg could be captured, then Richmond, the Confederacy’s capital city would fall shortly thereafter, and the war would be over. Repeated Union assaults on Petersburg’s fortifications failed to secure Union victory and a disappointed Grant prepared to lay siege to Petersburg, beginning a ten-month military operation. In July and August, Federals extended their lines around the city, cut railroad connections, and engaged in periodic battles outside the siege area. The summer of 1864 represented a low point for northern morale as operations on all the major fronts had failed or were stalemated, including those of Grant’s trusted western comrades, General William T. Sherman and General Philip Sheridan.

The absence of positive developments on the military side made prospects for Lincoln’s fall reelection gloomy. In fact, just as Democrats were gleefully preparing for a victory behind their presidential standard bearer, Major General George B. McClellan, Grant’s overall strategy finally fell into place. On September 2, Atlanta fell to Sherman. More good news came from the Shenandoah Valley where Sheridan defeated Confederate forces in a series of battles in September and October. Their combined victories made possible Lincoln’s re-election on November 8, 1864. As fall passed into winter, Union victory appeared more and more likely as Grant pressed the Confederate forces on all fronts.

The New Year brought grimmer news as Petersburg and then Richmond were abandoned by the rebels. The battle of Five Forks on April 1, 1865, destroyed the last supply line for the Army of Northern Virginia. After a series of engagements with Grant, Lee agreed to surrender. On April 9, 1865 at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, Grant dictated the generous terms upon which the war ended, and upon which the nation could begin the process of reconciliation. The fighting had stopped, but the war’s death and devastation guaranteed that efforts at reunion would be severely hampered by the lingering bitterness and hatred of the defeated Confederates.

Having led the Union army to victory, Grant emerged from the Civil War the second most important man in the country, next to Lincoln. He anticipated working in partnership with the president, securing the fruits of victory over which so much blood had been shed. The silencing of the guns saw Grant as commander of the army of the United States, a position he kept after Lincoln’s untimely death by assassination. For two years, Grant, the first four-star general in U.S. history, was a powerful presence within the Andrew Johnson administration, officially serving as general-in-chief overseeing the military part of Reconstruction policy. He could not disentangle himself from the political maelstrom that engulfed Johnson, eventually siding with the Republicans as they struggled to gain control over Reconstruction. Grant stood with Republicans in making sure that Union victory was secured on northern terms, restoring the rights and privileges of citizenship of white southerners, but also protecting the rights and establishing the citizenship of southern blacks.

The drama of Johnson’s impeachment trial ended just before the Republicans convened in Chicago to select their candidate for 1868. On May 21, a verdict was rendered: Ulysses S. Grant for president! Grant, who professed to loathe politics, accepted. Why? If we believe his own explanation, he felt a duty to say yes because “I could not back down without, as it seems to me, leaving the contest for power for the next four years between mere trading politicians, the elevation of whom, no matter which party won, would lose to us, largely, the results of the costly war which we have gone through.”

No other candidate could approach Grant’s stature in 1868. His name was forever linked to the martyred Lincoln and the sacrifice of the War. He had a ready-made image for his campaign that resonated with the average (northern) voter. Grant appeared to most of the people as a man who had character and upright morality. Like many if not most of his fellow countrymen, Grant had tasted defeat and failure. His early struggles and his determination to overcome them previewed the military commander who would not stop fighting until the war was won. Grant had a sharp intelligence that served him well in both plotting strategy and in dealing with the citizen-soldier of the Civil War. He made mistakes, but learned from them.

Moreover, he had a deep and abiding faith in democracy and democratic institutions. Nor was he without practical experience as an executive. As a commanding general he had focused resourcefully on objectives, had administrative experience, and had selected talented subordinates. Even his lack of political experience was, in the eyes of those who viewed politicians with contempt, a virtue. A vigorous campaign ensued, and in November the forty-six year old Grant, aided by newly enfranchised Southern blacks in states reconstructed by Congress, swept to victory aided by his famous campaign slogan “Let Us Have Peace.”

How did he do? The results are mixed. Today, vastly more Americans are familiar with the popular stereotype of President Ulysses S. Grant as a political ignoramus who watched helplessly as his two administrations became awash in corruption and chicanery than know about his genuine achievements. Historian and public intellectual Henry Adams’s mocking barb, “the progress of evolution from President Washington to President Grant, was alone evidence enough to upset Darwin,” has been widely used in several generations of history textbooks.

Despite his low presidential reputation, some historians have appreciated the difficulties Grant encountered during his two terms. Whether struggling to implement Reconstruction policy, advancing the United States’ goals in foreign affairs, advocating fiscal soundness, or implementing protections for Native Americans, Grant’s programs enjoyed some notable successes. Moreover, Grant possessed a political philosophy that mirrored that of the triumphant Republican Party that won the war, freed 4 million slaves, and ensured the continuation of the Republic. The freedoms promised by that new Republic – embodied in the 13th, 14th and 15 Amendments – would be protected by an unparalleled expansion of federal power. This was bound to be controversial and difficult to implement. President Grant pledged to use that power; and when he did, resistance was fierce, leading to retrenchment and withdrawal.

Indeed, Grant was a great champion of African-American civil rights, and proudly signed off on the 15th Amendment to the Constitution in 1870, describing the law enabling black suffrage as “a measure of grander importance than any other one act of the kind from the foundation of our free government to the present day.” When Grant took office in 1869 Republican-dominated Reconstruction governments in which blacks participated existed in all the former Confederate states except Tennessee. Although Grant did his best to uphold these "Black Republican" governments, violence prone white supremacists gradually overthrew them everywhere before he left office except in South Carolina and Louisiana. Even in those two states (which had black majorities) the Republican governments were sustained only by the presence of army detachments. Black Reconstruction failed not because of Grant, but because growing southern white resistance was matched by growing northern white apathy.

Although rank and file Republicans stuck by Grant, a disaffected reform wing of the Party was increasingly disillusioned by his presidency. They had hoped that he would be above partisanship and appoint the "best people" (like themselves) to office. The so-called “Liberal Republicans” called for tariff and civil service reform to stop the corruption of government. At first Grant did try to ignore political consideration in appointing his cabinet, but soon found that his independent course alienated the powerful Republican power brokers he needed to pass his programs such as Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York and Congressman Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts. Reform Republicans were also moving away from their earlier support of Republican Reconstruction and broke decisively with the Grant administration when they formed a new Liberal Republican party.

Their laissez-faire program included Civil Service Reform, low tariffs, a gold backed currency, and no legislation aiding special groups whether they were wealthy corporations or poor blacks. Grant could not stand the self-righteousness and superior airs of many reformers, but he recognized that some civil service reform would benefit the nation. He approved tariff reductions, and was a "sound money” man. His actions cut some of the ground out from under the Liberal Republicans. To the dismay of its leaders like Carl Schurz, the 1872 Liberal Republican convention nominated for President Horace Greeley, the eccentric editor of the New York Tribune. Although the Democrats also nominated Greeley, Grant easily defeated him by a popular landslide.

Grant's second term was marred by a severe economic depression following the Panic of 1873 and by the exposure of widespread corruption. Grant proved to be too trusting and while personally honest could be duped by unscrupulous friends and relations. For example Orville E. Babcock, Grant's personal secretary, was implicated in the Whiskey Ring that defrauded the government of millions of dollars in internal revenues. Grant's secretary of war, William Worth Belknap, sold an Indian post tradership. Not only was the Republican Party disintegrating in the South, but also declining in the North as a result of hard times and the issue of corruption. Republicans were soundly defeated in the election of 1874, returning the Democratic Party to control of the House of Representatives for the first time since before the war and dooming Grant’s Reconstruction policies.

Grant desperately tried to stem the rising tide of opposition. Determined to keep the country’s economy sound, he opposed even mildly inflationary measures and approved the Specie Resumption Act (1875) that would put the United States back on the gold standard on 1 January 1879. And despite flagging interest in aiding African Americans he signed the Civil Rights Act (1875) that guaranteed blacks equal rights in public places such as streetcars, theaters, and hotels and prevented their exclusion from juries. When from November 1876 to March 1877 the outcome of the presidential election was in dispute Grant acted in a dignified manner, supported the Electoral Commission Act (1877), and declared that he would not abuse his control of the army to declare Rutherford B. Hayes the winner.

Throughout his presidency, Grant remained steadfast in the belief that the goals of the war should be preserved even as the country’s enthusiasm for reconstruction of the South in the North’s image faded away. Grant’s final task as president harked back to his first, and perhaps most important achievement: to ensure a stable transition, this time in the disputed election of 1876. He succeeded and the country reconciled for good. Few, if any, professional politicians could have done better and most might have done far worse.

Returning happily to private life, Ulysses and Julia embarked on a world tour (1877-1879) that took them to Europe, the middle-east, India, China and Japan. The first time any ex-president had traveled so widely, Grant was greeted everywhere by huge crowds and saluted with grand reviews, parades, and speeches; he was wined and dined by kings and queens, generals and prime ministers. The nation’s press breathlessly recorded his triumphant tour, and noted that Grant seemed to symbolize a new American identity born of war, freedom, economic prosperity, and a nationalism leavened with democratic ideals. Coming home in 1879 to masses of adoring crowds, Grant was promoted unsuccessfully for a third term presidential nomination. Afterwards, he purchased a house in New York City and went into the brokerage business. His firm, Grant & Ward, went bankrupt in 1884 leaving him broke. Mortally ill with cancer of the throat, Grant retreated to the sickroom and wrote his Personal Memoirs. Regarded by many as the greatest military memoirs since Caesar's Commentaries, Grant recouped his fortune for his family and ensured his memory as one of our greatest generals if not presidents.

Grant’s legacy is deep and wide. By the time of his death on July 23, 1885 at Mount McGregor, New York Ulysses S. Grant was an icon in the historical memory of the war shared by a whole generation of men and women. Americans of that time compared Grant favorably to Washington and Lincoln. A little more than a decade later, Theodore Roosevelt maintained that among the past presidents, the trio emerging as the “mightiest among the mighty [were] the three great figures of Washington, Lincoln and Grant.” Roosevelt’s deeply appreciative comments reflected a widespread respect for Grant among a majority of the population. They believed that an appreciation of Grant could only come with the recognition that he was both the general who saved the Union and the president who made sure that it stayed together. On the same day that one and a half million Americans attended Grant’s funeral in New York City and countless others commemorated his life in cities and towns across the country, a newspaper headline provided the perfect epitaph for the accomplishments of General and President Ulysses S. Grant: “The Union, His Monument.”

Ulysses Simpson Grant (Born Hiram Ulysses Grant)

If you can read only one book:

Joan Waugh, US Grant: American Hero, American Myth. Chapel Hill North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Books:

Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. New York, New York: Charles L. Webster and Company, 1885 & 1886.

Josiah Bunting III, Ulysses S. Grant. New York, New York: New York Times Books, 2004.

Bruce Catton, Grant Takes Command. New York, New York: Little Brown & Co., 1969.

William S. McFeely, Grant. Norwalk, Connecticut: Easton Press, 1987.

Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822-1865. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000.

Jean Edward Smith, Grant. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001.

Organizations:

Ulysses S. Grant Association and Presidential Collection.

Assembles and publishes Grant’s correspondence and papers. Mississippi State University.

The Grant Monument Association.

A group dedicated to the preservation of Grant's tomb in Manhattan, New York

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volumes 1-31.

Published by the Ulysses S. Grant AssociationU.S. Grant: Warrior.

American Experience Series on PBS