Uncle Tom's Cabin

by David S. Reynolds

Uncle Tom’s Cabin widened the chasm between the North and the South, greatly strengthened Northern abolitionism, and weakened British sympathy for the Southern cause.

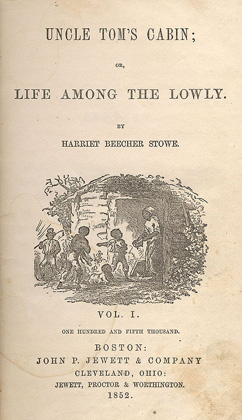

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s antislavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life among the Lowly, published nine years before the outbreak of the Civil War, set sales records for its time and inflamed the sectional tensions that led to the war. Written in protest against the infamous Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, the novel gained many readers when it first appeared in forty-one weekly installments in the Washington, D. C. newspaper the National Era from June 1851 to April 1852. It created a sensation when the Boston publisher John P. Jewett published it as a book in 1852. It “has excited more attention than any book since the invention of printing,”[1] remarked the minister Theodore Parker. Within a year, over 300,000 copies had been sold in American and some 1.5 million in Great Britain, and the novel had been translated into fifteen European languages.[2] And because reading the novel aloud was a favorite pastime of families and literary groups, it likely reached many more people. “Uncle Tom has probably ten readers to every purchaser,”[3] The Literary World declared in 1852. William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator hailed the “victorious Uncle Tom, with his millions of copies, and ten millions of readers.”[4]

What explains the novel’s success? Stowe skillfully used images from virtually every realm of culture—including religion, sensational pulp fiction, and popular entertainment—and brought them together in memorable characters and two compelling antislavery plot lines: the Northern one, involving the escape of the fugitive slaves Eliza and George Harris with their son, Harry; and the Southern one, tracing the painful separation of Uncle Tom from his family in Kentucky when he is sold into the Deep South.

Unlike other writers of her day, Stowe channeled these popular images to make a crystal-clear social point: Slavery was evil.

The unprecedented popularity of Uncle Tom’s Cabin came above all from its powerful appeal to the emotions. As Henry James noted in his autobiographical A Small Boy and Others, Stowe’s novel “had above all the extraordinary fortune of finding itself, for an immense number of people, much less a book than a state of vision, of feeling and of consciousness in which they didn’t sit and read and appraise and pass the time, but walked and talked and laughed and cried.”[5]

Sympathetic readers were thrilled when the fugitive slave Eliza Harris carried her child across the ice floes of the Ohio River and when her husband George fought off slave-catchers in a rocky pass. They cried over the death of the angelic Eva St. Clare and the fatal lashing of the good Uncle Tom. They guffawed at the impish slave girl Topsy and shed thankful tears when she embraced Christianity. They loved to hate the selfish hypochondriac Marie St. Clare and the cruel slave owner Simon Legree. They were fascinated by the brooding, Byronic Augustine St. Clare. They were shocked by the stories of sexual exploitation surrounding enslaved women like Prue and Cassy.

Many personal and cultural streams fed into the novel. Harriet Beecher Stowe was born in Connecticut in 1811. Her father, Lyman Beecher, was a leading Protestant clergyman who linked Christianity with social reform. He was the head of the so-called Benevolent Empire, a national network of evangelical reform groups dedicated to promoting temperance, missions, Sunday schools, tracts, and Bibles. The reform tradition he established would be carried on by several of his children, including Henry Ward Beecher, the celebrated clergyman who became active in several progressive movements, Catharine Beecher, a leader in women’s education, and Isabella Beecher Hooker, the pioneering suffragist.

In 1832, when Harriet was twenty-one, she moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where her father became president of Lane Theological Seminary. During her eighteen years in Ohio, Harriet got first-hand exposure to the slavery controversy. Cincinnati, across the river from the slave state of Kentucky, was the site of race riots, abolitionist lectures, public debates over slavery, and constant activity on the Underground Railroad.

In 1836, she was married to Calvin Stowe, a professor at the Lane Seminary, who shared her antislavery views. The couple had seven children, one of whom, Samuel Charles (known as Charley) died from cholera in 1849. Charley’s untimely death was one of the emotional triggers of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. “It was at his dying bed,” Harriet wrote a friend, “and at his grave, that I learnt what a poor slave mother may feel when her child is torn away from her.”[6] Her sorrow over Charley’s passing helped generate the pathos of scenes in Uncle Tom’s Cabin such as little Eva’s death and the account of Mary Bird sorting through her deceased son’s clothing, which prompted this passage: “Oh, mother that reads this, has there never been in your house a drawer, or a closet, the opening of which has been to you like the opening of a little grave?”[7] Throughout the novel, the loss of children by death or separation forms an emotional bond between whites and blacks.

This interracial bonding through shared grief was unusual for the era. Most white women didn’t think about enslaved black mothers when they lost a child, as Stowe did after Charley died. Stowe’s empathy derived from her personal associations with African Americans and her reading of slave narratives. She based the character of the runaway slave Eliza Harris on an enslaved woman of that name who in 1838 fled across ice shards on the Ohio River and found her way to Canada with the help of abolitionists. In another incident, her husband Calvin and her brother Henry took action to rescue an enslaved young woman who had escaped from a Kentucky master who came to Ohio in pursuit of her. They drove the runaway a dozen miles along a dark, solitary road to the home of the rugged John Van Zandt (renamed John Van Trompe in Uncle Tom’s Cabin), who took over protection of the girl and made sure she evaded her pursuers.

Other characters in the novel appear to be chiefly derived from slave narratives. Stowe read a succession of autobiographies of fugitive slaves—by Frederick Douglass (1845), Lewis Garrard Clarke (1845), William Wells Brown (1847), Henry Bibb (1849), and Josiah Henson (1849)—which contained sources for some of her characters and graphic details of the horrors of slavery.[8] For example, Josiah Henson, who took pride in being known as the original Uncle Tom, had been brutalized as an enslaved young man in Maryland and then became a forgiving Christian who was so honorable that, like Tom, he passed up a chance to escape when he led a group of slaves through the free state of Ohio. (Only later, when he was betrayed by his master’s brother, did Henson flee north.) Stowe’s George Harris seems based on Lewis Clarke, an extremely light-skinned Kentucky quadroon with “European” facial figures whose pious sister, like George’s sister, was sold as a sex slave in New Orleans but who escaped this fate by being purchased by a wealthy Frenchman who freed her and married her.

The Northern plot of Uncle Tom’s Cabin traces the flight to Canada on the Underground Railroad by the runaway slaves George and Eliza Harris’s with their child, Harry. The Southern plot follows the gentle, stoical Uncle Tom, who is sold away from his wife Chloe and their three children. For a time, Tom bonds with his kindly New Orleans master, Augustine St. Clare, and St. Clare’s daughter Eva, but after their deaths he is sold to the Louisiana plantation owner Simon Legree, who perversely hates the Christian Tom and commands his enslaved black overseers, Sambo and Quimbo, to whip him savagely. Tom’s death becomes a symbol of Christ-like sacrifice that is especially resonant because Stowe makes it clear that he will be meeting Eva and St. Clare in heaven.

Both the Northern and the Southern plots of the novel dramatize what was then known as the higher law, a phrase popularized by Senator William Henry Seward, who, in a speech referring to the clause in the Constitution that demanded the return of fugitives from labor, affirmed that there is “a higher law than the Constitution”[9]—the law of justice and morality that was holier than society’s laws, which supported chattel slavery. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was known as a higher law novel. Frederick Douglass’ Paper noted, “We doubt if abler arguments have ever been presented in favor of the ‘Higher Law’ than may be found here [in] Mrs. Stowe’s truly great work.”[10] A reviewer for the New Englander described “the tears which [Uncle Tom’s Cabin] has drawn from millions of eyes, the sense of a ‘higher law,’ which it has stamped upon a million hearts.”[11]

Stowe’s Northern plot directly flouts the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which imposed fines for federal officials who didn’t arrest runaway slaves. The villains of this plot are those who enforce the law—the slave-chasers Haley, Loker, and Marks. The heroes are the runaways and the kindly whites who assist them. The short, frail Mary Bird, who aids the fugitive Harrises, becomes a powerhouse of subversive energy when she castigates her politician husband, Senator John Bird, for having voted in the Senate for what she calls “a shameful, wicked, abominable law” (UTC, 69). John Bird, in turn, willingly puts aside his legal obligation to uphold the law when he takes pity on the fugitives and conveys them to the abolitionist John Van Trompe, who in turn forwards them to others along the Underground Railroad. Even as the Harrises make their way north, they remain in the malevolent grasp of the law. In the rocky pass scene, one of the slave-chasers tells George, “We have the law on our side, and the power,” which prompts George’s reply, “We don’t own your laws; we don’t own your country; ...We’ll fight for our liberty till we die” (UTC, 170).

If the Northern narrative exposes the injustice of the Fugitive Slave Law, the Southern one highlights the injustice of proslavery laws that made possible the sale of enslaved men and women. This domestic slave trade is condoned, Stowe tells us sarcastically, by “American legislators, …our great men” who declaim loudly “against the foreign slave-trade” (UTC, 115). Congress had abolished the international slave trade in 1808, leading to widespread complacency among Southern politicians. As Stowe writes, “Trading Negroes from Africa, dear reader, is so horrid! But trading them in Kentucky,—that’s quite another thing!” (UTC, 115). Stowe wrote in The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, her volume describing the factual bases of the novel, that the selling and buying of black men and women in the South was “the vital force of the institution of slavery” and “the great trade of the country.”[12] And in Uncle Tom’s Cabin she wrote that this business was “at this very moment, riving thousands of hearts, shattering thousands of families, and driving a helpless and sensitive race to frenzy and despair” (UTC, 384).

She constructed her Southern narrative strategically to accentuate the horrific aspects of the domestic slave trade. Tom’s being sold three times was by no means beyond probability. His owners—Shelby, St. Clare, and Legree—typify a range of Southern masters, from the kind to the cruel. Economics and chance cause Tom’s suffering, while law and proslavery religion sanction it.

The novel’s antislavery message came alive with special power for nineteenth-century readers because it was delivered through images characteristic of the popular culture of the time. Before she wrote the novel, Stowe had for years helped support her financially pinched family by writing stories and articles for magazines and newspapers. These early writings show that Stowe was fully immersed in different kinds of popular literature, which can be divided into the sensational and the sentimental. Sensational writings, usually published as pamphlet novels, were adventurous, exciting works that featured criminals, pirates, or other social outcasts involved in nefarious deeds that were often bloody or transgressive. In essays and letters, Stowe wrote about this sensational literature—she found much of it morally questionable, but she recognized its popularity, and she adopted some of its adventurous tropes and earthy language to dramatize the evils of slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

She was especially well attuned to the contrasting kind of popular literature, the sentimental, which was didactic and religious. Among her own early tales were stories about people who had visions of angels and heaven. Both Stowe and her husband took comfort in their own visions of spiritual beings, visions that were not unusual in that century of spirit rappings, séances, and conversations with the dead. Stowe’s early tales about angels directly anticipate Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in which the blonde Little Eva and the enslaved Uncle Tom have comforting visions of the other world. Another kind of fiction Stowe wrote were temperance tales, which emphasized the virtues of sobriety and the savagery and crime that came from drinking. In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the virtuous characters, mainly Northerners who help fugitive slaves, are clean-living types whose strongest drink is tea. The proslavery characters in the novel, in contrast, guzzle alcohol and are violent, despicable people—especially the slave owner Simon Legree, whose vicious treatment of Tom and other slaves is fueled by his heavy drinking.

Stowe also wrote early stories about sinless children. She took the romantic view of children as innocent souls who were living examples of Christian love. The stories she wrote on this topic led to the iconic character in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the dying Eva St. Clare, who sympathizes with slaves and who looks forward to a joyful afterlife.

And so Stowe became the first writer in American history to effectively combine the adventure and thrills of sensational fiction with images of angels, heaven, temperance, and the sinless child, which came from sentimental writing—all of it leavened by humor influenced by the minstrel shows that were popular at the time.

Stowe’s other early tales included ones in which she recreated Bible scenes in a deeply human way. This personal engagement with the Bible lay behind the vision that she said produced one of the most affecting scenes in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Stowe had come east in 1850 to Brunswick, Maine when her husband accepted a job teaching at Bowdoin College. As she told the story, she attended a communion service in a Brunswick church and was so moved by thoughts of the Passion that she had a vision of an enslaved man being whipped. As she recalled, she rushed home and wrote a descriptive vignette of a slave whipped to by death two other slaves at the command of their master. This piece became the climactic chapter of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

When the novel was first published, a New York journalist noted, its reception was “unprecedented in the history of bookselling in America,” with the press devoting “literally hundreds of columns” to it.[13] Putnam’s Monthly Magazine reported,

“Never since books were first printed has the success of Uncle Tom been equaled; the history of literature contains nothing parallel to it, nor approaching it; it is, in fact, the first real success in bookmaking, for all other successes in literature were failures when compared with the success of Uncle Tom.”[14]

For the first time, many Northern readers felt the horrors of slavery on their nerve endings. Frederick Douglass emphasized that Stowe’s novel won over the indifferent. “The touching, but too truthful tale of Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” he wrote, “has rekindled the slumbering embers of anti-slavery zeal into active flame. Its recitals have baptized with holy fire myriads who before cared nothing for the bleeding slave.”[15] A number of prominent antislavery reformers jumped on the Uncle Tom juggernaut. Previously, the antislavery movement had been divided between small, conflicting groups that were widely unpopular. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a force for unity among these fragmented groups. The radical abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison cried as he read the novel, which, he wrote, would be “eminently serviceable” to the antislavery battle.[16] Equally receptive to the novel were antislavery groups hostile to Garrison. Stowe was overjoyed by the embrace of her novel by the different antislavery factions. She said, “The fact that the wildest and extremest abolitionists have united with the coldest conservatives to welcome and advance my book is a thing that I have never ceased to wonder at.”[17]

Her message spread far and wide, even to those who had never heard of the novel. The numerous plays adapted from Uncle Tom’s Cabin made converts to the antislavery cause everywhere. Indeed, many people who had exulted in the recapture of fugitive slaves in the early 1850s did an about-face by the middle of the decade. One British professor attributed the shift to the Uncle Tom plays. He noted that night after night, audiences screamed and cried at scenes with a strong antislavery message and that “public sympathy turned in favour of the slave.”[18] One slave-holding South Carolina planter agreed. “Perhaps a slaveholder might have succeeded in catching his ‘property,’ as late as last year,” he grumbled in September 1854, “but that he certainly could not do so since ‘Uncle Tom’ and his troupe caught the popular fancy.”[19]

Of course, without the 1860 election of Lincoln, an antislavery Republican, it’s likely that the Civil War would not have begun when it did, in April 1861, because the secession of the Southern states, which triggered the war, would not have occurred. Uncle Tom’s Cabin played a role in the rise of the antislavery Republican Party. It shaped the political scene by making the North far more open to antislavery reform than it had been previously. Stowe was mentioned in political speeches, like one on the House floor by the Ohio congressman Joshua Giddings, who declared, “A lady with her pen has done more for the cause of freedom, during the last year, than any savant, statesman, or politician of our land. The inimitable work, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is now carrying truth to the minds of millions, who, up to this time, have been deaf cries of the down-trodden.”[20]

The novel and its iterations in plays, essays, reviews, and tie-in merchandise in America and Europe—like Tom-related card games, jigsaw puzzles, spoons, and handkerchiefs—contributed to the public’s openness to an antislavery candidate like Lincoln. By 1854, one journalist noted a growing shift among voters: “Much of Anti-Slavery truth, heretofore discarded . . . as fanatical, is now received and read by all. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, thundering along the pathway of reform, is doing a magnificent work on the public mind.”[21]

At the same time, Uncle Tom’s Cabin stiffened the South’s resolve to defend slavery and demonize the North. Most Southern states discouraged the book’s sale, and some criminalized it. “The wide dissemination of such dangerous volumes [as Uncle Tom’s Cabin],” a Richmond newspaper said, could lead to “the ultimate overthrow of the framework of Southern society.”[22] The Methodist minister Samuel Green, a free black in Maryland, was found guilty of possessing a copy of Stowe’s novel and was sentenced to ten years in the state penitentiary; he served half his term and was freed only during the Civil War.

Slavery’s defenders warned of the racial disruption the book might cause, including slave rebellions. At least twenty-nine anti-Tom novels were published before the Civil War. Many portrayed abolitionists as racist and corrupt and tried to show that enslaved blacks in the South were far better off than free blacks in the North.

After Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s publication, Stowe continued to promote her antislavery message. She made sure politicians she knew received copies of the novel, and she used whatever influence she could muster in the political scene—a forbidden sphere for women at the time—to challenge slavery. In early 1854, she was horrified by the bill proposed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois that threatened to open up the Kansas and Nebraska territories to slavery. She helped organize an antislavery rally in Boston and worked to distribute a petition against the bill. But to no avail: the Kansas-Nebraska Act became law.

The proslavery efforts in Kansas, combined with the Supreme Court’s 1857 ruling in the Dred Scott case, which said that blacks—slave and free—could never be U.S. citizens, led Stowe to embrace the antislavery warrior John Brown, who led a futile raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859, in an attempt to start a slave uprising. (He was later tried and executed for treason.) Stowe called him “a brave, good man, who calmly gave up his life to a noble effort for human freedom.”[23]

Some Southerners charged Stowe with having prepared the way for John Brown. A Virginia contemporary of Stowe said of Uncle Tom’s Cabin: “That book and old John Brown’s raid may be said to have brought on the Civil War.”[24] For Thomas Dixon, the author of pro-Southern bestsellers in the early twentieth century, Stowe and John Brown were intertwined. Without Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Dixon wrote, there would have been no John Brown, and thus no Civil War. In his 1921 historical novel The Man in Gray, Dixon insisted that Stowe had spread flammable material far and wide, and Brown had lit it with the torch of violence. In his novel, Dixon has Colonel Robert E. Lee, before Harpers Ferry, say of Uncle Tom’s Cabin:

It is purely an appeal to sentiment, to the emotions, to passion, if you will—the passions of the mob and the men who lead mobs. And it’s terrible. As terrible as an army with banners. I heard the throb of drums through its pages. It will work the South into a frenzy. It will make millions of Abolitionists in the North who could not be reached by the coarser methods of abuse. It will prepare the soil for a revolution. If the right man appears at the right moment with a lighted torch —.[25]

Stowe, however, hadn’t lost hope for a peaceful end to slavery. She was ecstatic over Lincoln’s victory in the presidential race of 1860, though at first she thought the Republicans didn’t go far enough in opposing slavery. She could hardly believe how far Northerners had come. It wasn’t long ago, she wrote, that open expressions of antislavery feeling would have been considered “rank abolition heresies,” whispered in the ear rather than aired in the street.[26] But now Northern men, women, and children everywhere were debating slavery and its evils.

Not that Northerners had converted to radical abolitionism. Garrison and his ilk were still widely considered extremists. Racism was rife. Eleven anti-abolition riots erupted in Northern cities between 1859 and the 1861 attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, which began the Civil War. Lincoln, trying to establish himself as a moderate, opposed abolitionism and John Brown before the war, focusing his efforts on keeping the Union together.

Nonetheless, Lincoln’s opposition to slavery was universally known. He had made that point resoundingly in his 1858 debates with Stephen Douglas while challenging him for his Illinois Senate seat. Lincoln stated, “I confess myself as belonging to that class in the country that believes slavery to be a moral and political wrong.”[27] He was elected president in 1860 on an antislavery Republican ticket. Stowe knew that, on the deepest level, he and she were in accord.

Her respect for Lincoln grew during the war, which under his direction became increasingly aimed at emancipating the slaves instead of simply preserving the Union. Her involvement with antislavery politics led to her historic visit to the White House in December 1862, a visit she made, as she wrote, “to satisfy myself that I may refer to the Emancipation Proclamation as a reality and a substance not to fizzle out at the little end of the hour.”[28] We don’t know whether Lincoln was swayed by his interview with her, but we do know that the meeting was cordial and was followed a few weeks later by his signing of the proclamation.

According to legend, Lincoln greeted Stowe by saying, “Is this the little woman who made this great war?”[29] This comment, which didn’t appear in print until 1896, is apocryphal, but a similar idea was expressed by others of the time, including a Southerner who declared that Stowe’s novel “did more than all else to array the North and the South in compact masses against each other.”[30] And in the early twentieth century, the historian W. E. B. Du Bois wrote of Stowe, “Thus to a frail overburdened Yankee woman with a steadfast moral purpose we Americans, black and white, owe gratitude for the freedom and union that exist in the United States of America.”[31]

In sum, Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin widened the chasm between the North and the South, greatly strengthened Northern abolitionism, and weakened British sympathy for the Southern cause. The most influential novel ever written by an American, it was one of the contributing causes of the Civil War.

- [1] Parker, speech of January 28, 1853, quoted in the National Era, February 25, 1853.

- [2] For the first-year sales figures, see Joan Hedrick, Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 223, 233. For information on foreign translations, see Margaret McFadden, Golden Cables of Sympathy: The Transatlantic Sources of Nineteenth-century Feminism (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999), 69.

- [3] The Literary World, December 4, 1852.

- [4] The Liberator, April 29, 1853.

- [5] James, A Small Boy and Others (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), 139.

- [6] Stowe to Eliza Lee (Cabot) Follen, December 16, 1853. E. Bruce Kirkham Collection, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center Library, Hartford, Connecticut.

- [7] Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life among the Lowly, ed. Elizabeth Ammons (New York: W. W. Norton, 1994), 75. Hereafter, page numbers from the novel are included parenthetically in the text.

- [8] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself (Boston: Published at the Anti-Slavery Office, 1845); Lewis Clarke, Narrative of the Sufferings of Lewis Clarke, During a Captivity of More Than Twenty-Five Years Among the Algerines of Kentucky, One of the So Called Christian States of North America, Dictated by Himself (Boston: David H. Ela, Printer, 1845); William W. Brown, Narrative of William W. Brown, A Fugitive Slave Written by Himself (Boston: Published at the Anti-Slavery Office, 1847);Henry Bibb, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave, Written by Himself (New York: Published by the Author, 1849); Josiah Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself (Boston: A.D. Phelps, 1849).

- [9] William Seward, Cong. Globe, 31st Cong., 1st Sess. appendix 205 (March 11, 1850).

- [10] Frederick Douglass’ Paper, April 1, 1852.

- [11] New Englander, 10 (November 1852): 590.

- [12] Stowe, The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (London: Clarke, Beeton, & Co., 1853), 279, 291.

- [13] New York Evangelist, 23 (May 27 1852): 87.

- [14]Putnam’s Monthly Magazine 1 (January 1853): 97-8.

- [15] Frederick Douglass’ Paper, April 29, 1853.

- [16] The Liberator, March 26, 1852.

- [17] Charles Edward Stowe, Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe Compiled from Her Letters and Journal (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1989), 169.

- [18] N. W. Senior, American Slavery: A Reprint of an Article on Uncle Tom’s Cabin (London: Longman, Green, Longmans, and Brown, 1856), 29.

- [19] National Era, September 8, 1854.

-

[20] “Speech of Hon. Joshua R. Giddings of Ohio, in the House of Representatives, December 14, 1852, in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, December 31, 1852.

- [21] National Era, March 17, 1853.

- [22] Richmond Daily Dispatch, August 25, 1852.

- [23] The Independent, 12 (February 16, 1860): 1.

- [24] Charles Campbell, quoted in David Macrae, The Americans at Home: Pen-and-Ink Sketches of American Men, Manners and Institutions (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1870), 324.

- [25] Thomas Dixon, The Man in Gray: A Romance of the North and South (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1921), 68-9.

- [26] The Independent, 12 (November 15, 1860): 1,

- [27] Rodney O. Davis & Douglas L. Wilson, eds., The Lincoln-Douglas Debates (Urbana, IL: Knox College Lincoln Studies Center/ University of Illinois Press, 2008), 193.

- [28] Stowe to James T. Fields, November 13, 1862. E. Bruce Kirkham Collection, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center Library, Hartford, Connecticut.

- [29] A version of this statement first appeared in Annie Fields, “Days with Mrs. Stowe,” Atlantic Monthly 78 (August 1896): 148.

- [30] Joseph Hodgson, The Cradle of the Confederacy; or, The Times of Troup, Quitman, and Yancey (Mobile, AL: n.p., 1876), 341.

- [31] Book Reviews by W E B Du Bois, edited by Herbert Aptheker (Millwood NY: KTO Press, 1977), 17-18.

If you can read only one book:

David S. Reynolds, Mightier than the Sword: Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Battle for America. New York: W.W. Norton, 2011.

Books:

Gossett, Thomas F. Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture. Dallas, TX: Southern Methodist University Press, 1985.

Hedrick, Joan P. Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Barbara Hochman. Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Reading Revolution: Race, Literacy, Childhood, and Fiction, 1851-1911. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011.

Parfait, Claire. The Publishing History of Uncle Tom's Cabin, 1852-2002. Farnhaml Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2007.

Lowance, Jr., Mason I., Ellen E. Westbrook, & R.C. DeProspo, eds. The Stowe Debate: Rhetorical Strategies in Uncle Tom's Cabin. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994.

Winship, Michael. "The greatest book of its kind": A Publishing History of Uncle Tom's Cabin. Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, 2002.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture. A Multi-Media Archive. Directed by Stephen Raillton, Department of English, University of Virginia, this website contains digitized primaryh sources on Uncle Tom's Cabine accessible on line.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the National Era. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, CT reproduces the entire text and key an provides additional analysis and resources to aid the user in understanding the book and its impact.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.