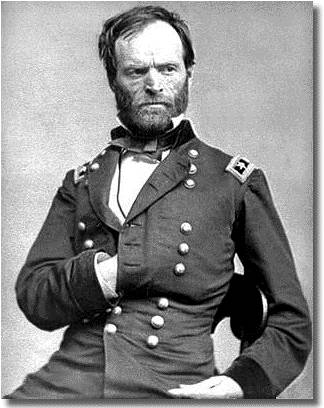

William Tecumseh Sherman

by John F. Marszalek

Biography of William Tecumseh Sherman

The new baby was born in 1820 Lancaster, Ohio, into a family with powerful roots in Colonial America. For generations, they had been builders of New England’s Connecticut society. In 1811, father and mother, carrying their first born across their horse saddles, left the Atlantic seaboard and migrated to Connecticut’s “Western Reserve,” located in what would later become the state of Ohio. The baby’s father, Charles R. Sherman, had attended Dartmouth College and was a lawyer. His mother, Mary Hoyt, came from the family of well-to-do merchants, and, unlike most women of her time, attended a female seminary. When William Tecumseh Sherman was born to Charles and Mary Sherman, he was their sixth child, with five yet to come. By the time of his arrival, his family was well established in the growing western community of Lancaster, Ohio, connected to the outside world by its location on Zane’s Trace and only twenty one miles from the famous National Road. Cump, as the baby came to be known in the family and among friends, had an enjoyable secure early childhood.

All this changed in 1829. While serving as a collector of internal revenue for the national government, Charles Sherman had allowed his deputies to accept a variety of paper money in payment for taxes. When the national government decreed that it would only accept specie or Bank of the United States notes, Sherman faced a crisis. He found himself stuck with piles of worthless paper. He could have tried to duck responsibility, but instead he determined to pay off all this debt from his earnings as an attorney. While on the circuit, however, he died suddenly. In a flash, his secure family was reduced to a widow and a large brood of children, without a husband and father, with no finances. Mary Sherman could not afford to keep the family together, so the children were parceled out among relatives and friends, nine year old Cump Sherman walking up the hill to live in the home of the next-door neighbors, the Ewings.

Thomas Ewing was a leading attorney and businessman, and later he would become a major force in the national Whig Party. He and his wife, Maria, had seven children of their own, but they welcomed the young Sherman into their home and always treated him as one of their own.

This traumatic series of events played a major role in the formation of William Tecumseh Sherman. Although he was a full member of the Ewing family, he never overcame the shock of losing his father and being sent to live with others. He spent his entire life determined never to be penniless again or let his later family suffer what he considered was the humiliation of family disintegration. He lived with the prestigious Ewings, but he always saw himself as one of the financially destitute Shermans. He fought to get out from under that psychological burden.

When Sherman reached sixteen years of age, Ewing secured an appointment to the United States Military Academy for him. From 1836-1840, the young man spent four years doing good work academically but regularly gaining a pile of demerits for a variety of military transgressions. As a result, he lost two places in class standing and graduated 6th in his class. Yet, at West Point, he found the togetherness that he had not experienced with the Ewings. Sherman’s four years at West Point were hardly idyllic, because, in truth, he found the experience grinding. In later years, however, he would think back with nostalgia to that period, in reality remembering camaraderie and not the harsh conditions.

Upon graduation, Sherman entered the army. Tours followed in the South: in Florida’s Seminole War (1840-1842); at Fort Morgan on Mobile Bay, Alabama (1842); and at Fort Moultrie in Charleston harbor (1842-1846). Then he was ordered to California, a back water of the Mexican War, sailing around Cape Horn and remaining on the Pacific Coast from 1846-1850. During his years in the South, he learned about that region’s geography and customs and became friends with many of its people. He came to accept slavery as a way of life and defended the institution during the Civil War and Reconstruction. In California, he spent his time doing paperwork and trying to keep obstreperous gold miners in line while trying to survive the impact of inflation on his meager army salary. He worried about missing the main fighting of the Mexican War and thus falling behind his contemporaries.

It was during this time that his personal life changed fundamentally, and this circumstance reinforced many of his earlier insecurities. He had fallen in love with

Ellen Ewing, his foster sister, and the daughter of his powerful protector Thomas Ewing. They were married in 1850. Ellen and her family continually pressured Sherman to leave the army and take over directorship of the family Ohio salt works. Ellen also wanted him to become a practicing Catholic. Sherman kept hoping that Ellen would change her mind. The thought of moving closer to the Ewings and/or working in business with them was frightening to Sherman and only increased his determination to make it on his own. He similarly had no interest in Catholicism.

In 1850, Sherman traveled from California to Washington bearing messages to commanding general Winfield Scott. At that time, he and Ellen were married in a ceremony which was witnessed by the major power brokers in the capitol including President Zachary Taylor, in whose cabinet Thomas Ewing was Secretary of the Interior. Cump and Ellen had not settled any of their profound disagreements over their futures, but they confidently became man and wife anyway.

Cump Sherman quickly let it be known that he would not be leave the army or go to church, while Ellen Sherman decided to spend as much time as possible with her father and family in Lancaster. Even when children began to come, she returned to her childhood home as often as she could. Sherman served in the army in St. Louis and then in New Orleans from 1850-1852, often lonely for his departed wife and first born daughter. His fears of a financial failure like that of his father eroded his will and convinced him that he could not remain in the military. Yet he did not want to run the family salt works near Lancaster. The solution was to accept the offer from an existing St. Louis bank to become founding manager of its planned San Francisco branch. Ellen continued to want to remain near her parents, but she compromised and went west with her husband, leaving their first born child behind in Lancaster with the Ewings. The result was further marital frustration.

The banking business was initially successful, but in 1855 there was a bank panic, resulting in a run on every bank in San Francisco. Sherman handled those matters well, and his reputation soared. When vigilantes took control of the city, however, Sherman, then commander of the local militia, tried to intercede but received little support, even from the state’s governor. He quit his post in disgust, and, to add to the difficulties, Ellen Sherman went home for a seven month visit to see her parents and child Minnie, leaving behind two younger children under Sherman’s care. Sherman only grew increasingly depressed, and his asthma worsened, adding to his low feelings.

Then the St. Louis bank decided to close its San Francisco branch, and Sherman was without a job. He worried that he was repeating his father’s earlier financial failure.. He found employment with a New York bank, but the Panic of 1857 caused that venture to fail, too. Ellen was pleased at the California failure because it allowed her to return to Lancaster. These disappointments pushed Sherman over the brink. He decided to accept the long-standing family offer to become manager of the Ewing salt works. However, at the last moment, two Ewing sons asked him to join them in an attorney/real estate venture in Kansas. He did so, only to see this venture collapse too. Sherman grew so desperate about his financial future that he asked army friends for help. Thanks to later Union general Don Carlos Buell and later Confederates Braxton Bragg, and P. G. T. Beauregard, Sherman, in 1859, became the founding superintendent of the Louisiana Military Seminary. He had to go south by himself, however, because there was no available housing for his family. A house was going to be built, and he expected Ellen to join him when it was completed. She and the rest of the Ewings did not respond enthusiastically, however. Sherman was finding success and financial security in Louisiana, but the Ewings demanded that he take a position with a London bank, so Ellen could remain in Lancaster. He almost took the position, but at the last moment he decided to stay at the Seminary and demanded that Ellen and his family join him there.

As Sherman’s personal life disintegrated, the nation underwent similar crisis. In late 1860, early 1861, southern states began seceding from the American Union. Sherman had let it be known in the fall of 1860 that, if Louisiana seceded, he would resign his position. He had come to view the Union as essential to his personal success, and secession as an exemplification of the kind of anarchy that was undercutting his life. He passionately insisted on national order to insure order in his own life, the stability that would prevent financial collapse.

In February 1861, after Louisiana seceded, Sherman sadly left the most satisfying job he had ever had. He moved to St. Louis to become president of a street railway company, refusing to re-join the United States Army because he believed that President Abraham Lincoln and the North generally were not taking the South seriously enough. The Ewings and John Sherman, a brother and a rising Ohio politician, called for him to return to the army and battle against secession. Sherman was afraid to do so, fearing that he would only go down with the sinking Union ship. That May, however, he gave in and rejoined the army in the rank of colonel. He first served as inspector general for Commanding General Winfield Scott, and then he was given brigade command in Daniel Tyler’s division of Irvin McDowell’s army. He quickly became disgusted with what he considered the incompetence of the volunteer soldiers, but he played a major role in attempting to rally defeated Union troops at Bull Run (Manassas) in July 1861. Fear of failure increasingly dominated his life as he pondered the future of the war.

The fall of 1861 only saw Sherman’s fate drop even more. He accepted Lincoln’s offer to serve as second in command to Robert Anderson in Kentucky only if he would never be asked to hold top command. When Anderson had to resign for health reasons, however, Sherman was forced to take his place. He constantly worried about failure, seemingly demonstrating to those who saw him, particularly newsmen, that he was losing his grip on reality. He insisted that Confederates were about to over-run Kentucky and when he was relieved and sent to Missouri to serve under Henry W. Halleck, he repeated the same dire warnings there. Finally, he had to go home, to Lancaster, to the Ewings, to recuperate from severe depression. While there, a Cincinnati newspaper article called him insane. He briefly contemplated suicide. When he returned to Missouri, he was demoted to training recruits. His depression was serious, sparked by his worry that there was no hope for the Federal war effort.

Halleck, however, brought him along slowly and when Sherman came into contact with Ulysses S. Grant, his spirits begin to rise. He began doing effective work. He sent troops forward to Grant, as his new friend captured Forts Henry and Donelson, in February 1862. Then he became division commander in Grant’s army, fighting off charging Confederates at Shiloh in April 1862. Having suffered attacks from newsmen himself, he defended Grant against similar attacks after the surprise at Shiloh. When Halleck merged separate armies to form a juggernaut of over 100, 000 troops, Sherman was part of that huge force which took Corinth in May 1862. It was during this time that Sherman convinced Grant not to quit the army in anger over Halleck’s alleged maltreatment.

Sherman served well as military governor of Memphis in late 1862, but suffered a repulse at Chickasaw Bayou, near Vicksburg in December. He grew so angry at the news reports of Thomas W. Knox of the New York Herald that he court martialed the reporter, the case reaching as high as Abraham Lincoln. In the end, Knox was only sent out of the area, but Sherman set the precedent of being the first general to court martial a member of the press. He bounced back quickly from his defeat at Chickasaw Bayou and played a major role in the Vicksburg campaign. He and Grant grew ever closer together, their friendship bonded by their complete trust in one another.

Throughout the war Sherman kept his family from visiting him because he thought it was unmilitary. He relented after the Vicksburg victory, and his family came for an extended visit to his camp along the Big Black River. Tragically, his son Willy, his namesake and the child who most shared Sherman’s interest in the military, caught a fever and died. Cump and Ellen never recovered from their grief, Sherman blaming himself for allowing the family to visit him in an unhealthy place.

He had little time for grief, however, because when Grant was made commander over the entire western theater of the war, Sherman took his place in command of the Army of the Tennessee. Quickly Grant and Sherman had to rush to Chattanooga to raise the Confederate siege of Union troops in the city, and then he had to hurry to Ambrose Burnside’s aid in Knoxville. In February, 1864, he conducted his Meridian Campaign, the first use of his philosophy of destructive and psychological warfare. Instead of killing Confederates, many of whom he considered to be his friends from his West Point, early army, and military seminary days, he decided to work for Union victory through the destruction of southern property and the destruction of the southern psyche.

At this time, the Union army successes in the West (and the lack of success in the East) resulted in Grant being named commanding general of all Union armies. Sherman took Grant’s place as commander of the Federal effort in the West. The two men planned a coordinated campaign which began on May 6, 1864 with Grant attacking Lee in Virginia and Sherman attacking Joseph E. Johnston in Georgia. Sherman continually attempted to flank Johnston, who successfully parried these efforts and fell back. When Jefferson Davis fired Johnston in anger over his defensive warfare and replaced him with the aggressive John Bell Hood, Sherman inflicted large casualties on the Confederates and in September 1864 took control of Atlanta, in time to influence the presidential election in favor of Abraham Lincoln.

Sherman now put his concept of destructive war into full use. Leaving Atlanta in November 1864 and torching all its war-making capacity (but not burning the entire city into ashes, as mythology would have it), Sherman began his march to the sea. His army, extending in columns, 40 to 60 miles wide in all, wrecked devastation on Georgia but few people were physically harmed or killed. Sherman used purposeful destruction to demonstrate that the Confederacy was a hollow shell, that its government could not protect its people. In fact, Confederate soldiers, civilians, deserters, and fugitive slaves produced destructive violence of their own, adding to the fear that Sherman was inflicting, to get southerners to quit the war.

Sherman regularly said that he favored a hard war but a soft peace, calling himself the South’s best friend once it surrendered. When he completed his march through Georgia and captured Savannah, he indeed instituted a soft peace. He had no interest in killing or maiming people once he was victorious over them. At that time, he wanted further punishment to cease.

The war was not over, however. Sherman now marched from Savannah and through the Carolinas, escalating destruction. His soldiers increased the havoc because they blamed South Carolina for causing the war. Sherman and his men did not burn Columbia, the state capital, as was later argued. The destructive fire actually was the result of the retreating Confederates lighting cotton bales in the street, high winds fanning the flames, and the intoxication of Union soldiers, southern white civilians, and black slaves.

Sherman’s army next marched through North Carolina, and here destruction was clearly less severe. Confederates made their last stand under Joseph E. Johnston, recently returned to command, at Averysboro and Bentonville. In mid-April, he and Johnston met and agreed to such soft surrender terms, that some in Washington began to call Sherman a pro-southern traitor. He had to renegotiate less southern-friendly terms.

During Reconstruction, Sherman indeed tried to be the South’s best friend, supporting the white South’s anti-citizen position concerning freed people. He was, however, stationed in the trans-Mississippi area, so he played little role in military Reconstruction. When Grant became president in 1869, Sherman took his place as commanding general, a position he held until 1883, in the process battling a series of secretaries of war over jurisdictional powers. He had a one year tour of Europe, wrote his memoirs, and, in 1879, he even visited the sites of his war campaigns, receiving a friendly welcome in the South. After he retired in 1883, he published articles on the Civil War, belonged to a variety of veterans’ organizations, and gave a multitude of speeches, many of them of the after-dinner variety. He gained a reputation for kissing young girls, and, since his wife Ellen refused to accompany him to his many social engagements, he was often seen with a variety of women on his arm. He was a very popular figure in American society.

Ellen Sherman died in 1888, and Sherman went into depression, his children and his friends keeping him active, blunting the sadness. Three years later, in 1891, he died of a respiratory problem. He was one of the last living symbols of the Union victory in the Civil War. During every presidential cycle after 1868, there had been a move to run him for president. Even some white southerners supported this idea, but he always refused, stating in 1884, for example: “I will not accept if nominated and will not serve if elected.” His speech was full of such memorable comments, and, later, he was particularly remembered for “war is hell.”

William Tecumseh Sherman is today recognized for his strategic and logistical genius, and his elevation of psychological and destructive methods to an important way of waging warfare.

William Tecumseh Sherman

If you can read only one book:

John F. Marszalek, Sherman, A Soldier’s Passion for Order. New York: Free Press, 1993; Collier Paperback, 1993; Carbondale Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, Reprint, Paperback, 2007.

Books:

John F. Marszalek, Sherman, A Soldier’s Passion for Order. New York: Free Press, 1993; Collier Paperback, 1993; Carbondale Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, Reprint, Paperback, 2007.

William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman. New York: Appleton & Co., 1875.

Lee Kennett, Sherman, A Soldier’s Life. New York: Harper Collins, 2001.

Stanley P. Hirshon, The White Tecumseh: A Biography of William T. Sherman. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997.

Steven E. Woodworth, Sherman. Waterville Maine: Thorndike Press, 2009.

Michael Fellman, Citizen Sherman: A Life of William Tecumseh Sherman. Lawrence Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1997.

Charles Edmund Vetter, Sherman Merchant of Terror, Advocate of Peace. New Orleans: Pelican Publishing Company, 1992.

Charles Royster, The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson, and the Americans. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1991.

John F. Marszalek, Sherman’s Other War, The General and the Civil War Press. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1981; Kent Ohio: Kent State University Press, Revised Edition, 1999.

Brooks D. Simpson and Jean V. Berlin, Eds., Sherman’s Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860-1865. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Organizations:

Sherman House Museum.

137 E. Main St. Lancaster, Ohio 43130 | Laura Bullock, administrator

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

Sherman Family Papers.

Archives of the University of Notre Dame, (available on microfilm)William T. Sherman Papers.

Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, OhioWilliam T. Sherman Papers.

Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (available on microfilm)